Under the banner Southern Spirit-Aspects of the Negev in Contemporary Israeli Art new life was breathed last month into the Museum of the Negev, a historical building in the old city of Beersheba that has served intermittently since 1953 as an exhibition center for arts, and arts and crafts. This show, the first curated by the Museum’s new director Dalia Manor, and the first for years to feature works of prominent contemporary artists at this venue, has now relocated to Tel Aviv. It is certainly worth a visit.

None of the eleven participating artists, mostly photographers, is interested in objective documentation of the Negev. Their aims are far more complex. Like archeologists or sociologists, they appear to be tracking down evidence from the past or the present that might bestow some defining cultural or historical identity on this region with its endless open spaces of desert and sky.

Gaston Zvi Ickowitz, who spent his childhood in Beersheba, is amongst these photographer-archeologists. Some of his images are mysterious, touching on the biblical history of this region. Entrance to Sodom, for example, depicts the mouth of a cave blocked by large stones. A simple enough subject, but one that comes across as a study in contrasts of light and darkness, a metaphor, perhaps, for the battling forces of good and evil.

Ohad Matalon has produced a most original metaphor for the unfufillment of Ben-Gurion’s Zionist dream to settle the Negev and make the desert bloom. He has photographed a piece of sturdy agricultural equipment ‘lost’ in the desert. After digital manipulation, this structure is transformed into a frail and vulnerable object.

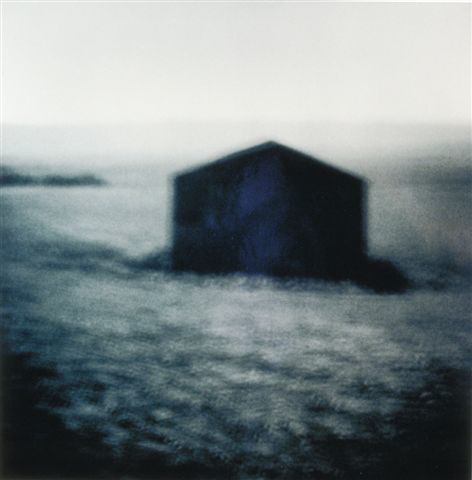

The vagaries of memory are the subject of Michal Rovner‘s contribution: chromogenic photos of an abandoned shack, perhaps once a Bedouin dwelling. Printing and reprinting this image, distorting its size and color, she has stripped it of distinctive features so that it becomes a shadowy form, a memory trace of something once seen and almost forgotten.

Abandoned military equipment and buildings in the Negev are the subject of several photo series having critical/political content by Gilad Ophir and Roi Kuper. Ophir’s imagery ranges from a Bedouin tent constructed from the camouflage netting of a tank to views of a derelict swimming pool at the site of the now defunct Kiziot (Ansar) military base. Kuper also turns his attention to this place, photographing the remains of the prison that operated there for several decades. Only its foundations remain, barbed wire looping over the high outer walls, its floors sprouting clumps of dry vegetation.

Gilad Efrat (one of two painters in this show) has also created an Ansar series. In the particular example on view, the outer wall of the prison with its guard tower has been elevated so that it floats in the sky. Broken free, as it were, from the bitter associations of this place of confinement and punishment.

One of the more intriguing themes in this show relates to the people who live or work permanently or temporarily in these peripheral cities: Bedouins, soldiers, immigrants from North Africa, Russia, Ethiopia and India.

Attesting to this cultural mix is the photo that Yosef Joseph Dadoune has taken of the wall of a defunct factory in Ofakim. Defaced by graffiti, a sophisticated sketch of the body of a horse is set alongside crude drawings of tanks and people, and slogans in Hebrew and Arabic. Dadoune’s film of the same name produced in 2008, showing in the gallery, expresses through symbols and metaphors, the realities of life in these desert communities and the hardships and bleak future facing their young people in particular.

The importance in maintaining one’s traditions, at least in the manner of dress, is illustrated through the black and white portraiture of Khadar Oshah, a resident of Rahat. Their sketchy character, achieved by employing chemical materials on photographic paper, seems a deliberate ploy to create images that transmit a sense of transience and lack of security.

Pavel Wolberg has taken his camera into the apartment of an elderly Russian lady which is furnished in an old fashioned Northern Europe style. She sits on her bed, curtains fully drawn as if to keep out not only the glaring light of the Negev, but also a community whose ways she finds foreign.

Finally, one should mention Sharon Ya’ari’s photo documenting a unique phenomenon: the coming of the sport of cricket to Dimona. Scrubland frames a distant view of figures playing cricket on a make-shift pitch. One may ask how this very British sport arrived in this region? The answer is that it was originally transported from England to India way back in the 1770s; and now, immigrants from that country have settled in the Negev bringing the game with them.

The Genia Schreiber Art Gallery, Tel Aviv University (main entrance). Till September 22, 2011.