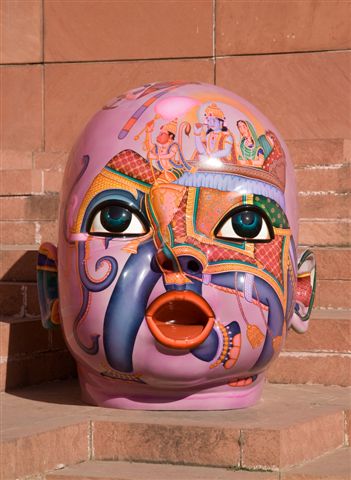

A monstrous baby’s head, constructed from fiber resin and painted in lurid colors is sited outside Roundabout: Face to Face; an exhibition of 60 works –mainly portraits and figures – selected by curator Varda Steinlauf from the 400 piece collection of US born David Teplitzky. On display are paintings, sculpture and installations by well known contemporary artists from Asia, Australia, New Zealand, Russia, Britain and Israel.

This baby’s head is ornamented with imagery that alludes both to India’s past history and to present times. Here one finds that mythical scenes appropriated from Indian miniatures have come together with a painting of a top-hatted Englishman smoking a hookah – a scene alluding to the era of the British raj in India. Also, one sees (if one stands on tip-toe) that a helicopter, symbol of modernity, has been painted on the crown of the baby’s head.

This eye-catching piece, one of an iconic series by Indian artist Chintan Upadhyay, is pertinent to many of the themes explored in this show: namely the clash or merger of different cultures, religions and ideological beliefs. The focus in this show is also on the struggle of ethnic groups to maintain their identity in today’s global village, a place described by Steinlauf where “Consumerism has become the new God.”

This statement is well and wittily illustrated in Buddha Market: Self critique, by New York based Nepalese artist Tenzing Rigdol. In this wall piece where traditional imagery is swamped by outside influences, religious texts as well as a map of America form the background to the stately form of a Buddha, his figure and head majestically framed by strips of rich brocade. However, the face and bosom of this deity are filled with photographs of perfume and cosmetics and other goods imported from the West.

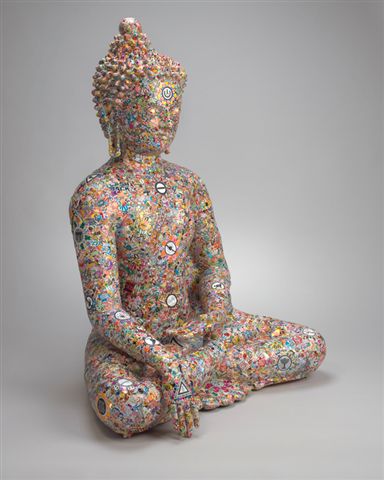

Another sculpture of Buddha relates to the same theme. It is titled Pair of Golden Fishes (the reference is to the eyes of Buddha) and is by Gonka Gyatso, a cosmopolitan artist (born in Tibet, studied in Beijing prior emigrating via India to England). Like many of his colleagues, Gyatso employs contemporary materials for his work even though it is based on ancient imagery or traditions. In this instance, Gyatso has sculpted his Buddha figure in polyurethane, and then totally covered it with gaudy stickers of cartoon characters, flags and forms of transport, together with twists of paper resembling shiny candy wrappers.

In a second, two-dimension version worked on paper, Gyatso has again covered the figure of Buddha with all manner of stickers. But here, respect for this deity is further diminished by the presence of cloud-like bubbles surrounding his figure. They enclose what are apparently the prayers of his consumer-orientated followers. “Dear Lord Buddha, let me win the jackpot” is one telling example.

Political and social criticism are at the core of eye-catching sculptures by eminent Chinese artists Huang Yan and Zhu Wei. Both feature Mao Tse-tung, a man whom artists of the past only dared to portray in a flattering light. But all this has changed. Huang Yan depicts Mao as a miniature porcelain figure. Hands raised, he appears to be applauding his own achievements. Painted all over his body are depictions of Nature that recall the Blue Willow design, used today as decoration for kitchen and house-ware.

In this work, Huang Yan looks back to the noble tradition of Chinese landscape painting, but he breaks with tradition, replacing paper or silk with porcelain, and opting to ‘use’ the human body (rarely depicted in Chinese landscape painting), as so many leading Chinese artists are intent on doing today.

Zhu Wei shows two identical renderings of Mao from his China China series of painted aluminum sculptures. Even though they are dwarf-like in size, they make a monumental impression. In giving their bodies a weathered appearance Zhu Wei seems to be linking these figures to China’s ancient art treasures, the terracotta figurines from the Han dynasty unearthed from burial pits.

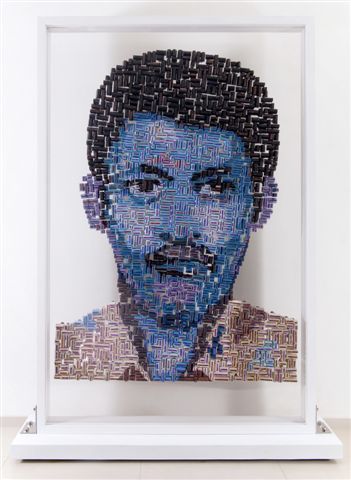

The portrait of an unidentified face by Indian artist Reena Saint Kallat relates to the horrifying fact that thousands of children go missing in India every year, many of them forced into prostitution. Coming close, one sees that this is no ordinary portrait, but a face constructed from hundreds of rubber stamps enclosed in Plexiglas. Each stamp bears the name of a missing person in some part of the country. This is a clever idea but one that Saint Kallat has used before (e.g. stamps bearing the names of laborers who built Agra’s Taj Mahal). Consequently, one gets the impression that the novelty of using these objects could easily turn into a gimmick. In truth, like a number of works in this exhibition, the artistic value of Saint Kallat’s portrait is outweighed by the message it carries.

This is also true of Release from Suffering, a pleasant but simplistic painting by Nortse, a Tibetan artist. It shows a bound youth, releasing flags and butterflies (symbols of freedom) into the air. A much worthier piece is a sculpture entitled Coco by Irish artist Kevin Frances Gray. It depicts a black Madonna and child: a girl in tattered street clothing holding a baby. The universal message of compassion for the needy and underprivileged is clear, but this is first and foremost a striking work of art.

Artists from Indigenous communities make a strong impression. Among them is veteran Dinny Nolan Tjampitjinpa who shows an earth-colored pattern painting made up of dots and symbols. The meaning of this picture derives from the Aboriginal belief in the Dreamtime when the earth received its present form and cycles of life began.

Hung alongside his work is a homage to Nolan, a highly respected personality, in the form of a romantic painting by Sydney-born artist Tim Johnson. An ideal participant in this exhibition, Johnson, a visionary, searches through his art for spiritual connections between countries and cultures. Not surprisingly, he has inserted into this painting, aside from a portrayal of Nolan himself at work, scenes that relate both to Buddhist and Aboriginal traditions and philosophies.

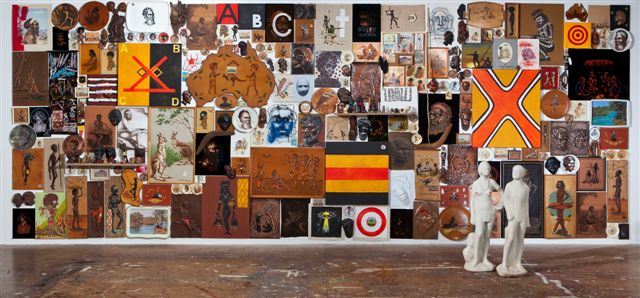

The bitterness and anger felt by the Aboriginal people for the injustices meted out to them by white Australia is expressed in an original way through Tony Albert’s installation A Collected History. This is in the form of a large wall installation comprising hundreds of re-worked objects, original paintings and decorative items assembled over an eight year period. Some are touristic items featuring the ‘happy’ Aboriginal, others relate directly to their sad history. Among this miscellany, one notes the single word Sorry pasted over a photo of an Aboriginal child. The reference here is to the formal apology offered to Australian’s indigenous population by Prime Minister Kevin Rudd in February 2008. Albert’s work, created over a period that extends beyond this date, effectively illustrates that apologies are not enough.

These are only a few of the highlights in a provocative exhibition which is certainly worth a visit.

Joseph and Rebecca Mayerhoff Pavilion, Main Building, Tel Aviv Museum of Art, till April 14.