It’s always so hard to talk about Israel. Every word, thought or reference point can be seen from several different perspectives, diverging and conflicting narratives move in different directions, and it’s always a matter of life and death. It’s almost impossible to talk about Israel in a work of art without sounding like a barrage of political slogans, foregone conclusions leading to a dead end: when someone is telling you what to think, then that conversation really has nowhere to go. But every now and then, someone finds a way to approach the impossible…

Zvi Sahar’s The Road to Ein Harod, based on the novel by Amos Kenan, is a feat of performance and storytelling, an action thriller wrought with artistry and symbolic resonance. In a dystopian Israel that has been taken over by a military coup, one man strives to reach the only vestige of rebellion: Free Ein Harod. He does not know if this rebel camp really exists, or whether the rebels are still free or even alive. All he has to go on is a fragmented radio broadcast, but he has no other alternative.

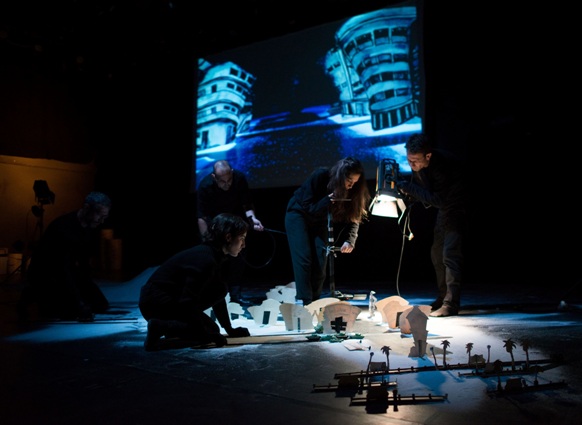

Sahar takes this story of violence, oppression and the will to survive, and conveys it in a pared-down, poetic form he has developed over the past several years: Puppet Cinema. Onstage are actors, puppeteers and a camera-person, with the camera’s perspective shown on a large screen at the back of the stage. It’s a shifting collage of image, sound, and movement, telling a story that is several stories at once. A thousand pounds of salt form the landscape, and a faceless puppet is the hero of this tale. There is a childlike sense of wonder to the scene created onstage as tiny buildings, their Bauhaus style rounded balconies sketched in lively lines, form the city of Tel Aviv amid the salty dunes, traversed by toy trucks in military green. Just above, the illusion becomes real – building writ large on the horizon, a city street at night. A sweep of the hand, and the terrain shifts, the imaginary world rearranged, transformed.

Kenan’s original text is a first person narrative. In this production, Sahar, an actor with an expressive presence and keen sense of rhythm, embodies protagonist and narrator – at times speaking directly to the audience, and at times providing narration that is the voice of the puppet. In some sense there are three narratives at work: the film onscreen; the visible “backstage” as scenes are set up and puppets manipulated while the camera follows the action from its own perspective; and the actors onstage, as primarily Sahar, but at times also other characters, are represented by the actors.

Sahar remains true to Kenan in the best sense of the word. The text is edited for the stage, where Kenan’s narrator is more reflective, Sahar’s narrator does not have time to think, he is a man of action. Yet both the novel and performance begin with a song, and develop their meaning through symbols and associations. The song is an old one: Layla Dmama (literal translation from Hebrew: Night Silence), with lyrics by Naomi Brontman and music composed by Moshe Bik. Evoking the spirit of socialist-Zionist pioneers, the song (whose words were written by a 16 year old girl at the legendary agricultural school Nahalal) is an expression of nostalgia for days gone by that will not return: “the moon rises and with it, memories rise.” At the time Kenan published his novel in 1984, perhaps this was still a reference one could count on, one of those songs “everyone knows.”

Yet the song itself is nostalgic for idyllic, halcyon days, an ideal community that was perhaps more dream than reality, such too is the reference to Ein Harod. Ein Harod is a real place, a kibbutz founded in the 1920s, that suffered an ideological split in the 1950s, becoming two separate kibbutzim. Yet it represents so much more. In his evocation of shared songs, dreams, symbols and values, Kenan is also posing questions, questions that reverberate with force in Sahar’s work.

Most Israeli audiences today would not recognize this song, and that absence of familiarity becomes yet another layer of meaning in this story. Kenan wrote a character who was at a critical distance from the beliefs and ideals of Israel’s founders and of his own youthful sense of identity that included his experiences as a soldier. Sahar is creating his own take on this text from a contemporary vantage point, in this work that is so deeply involved with cultural ideals and mythology, it is important to remember that Kenan has acquired mythological stature in Israeli culture. And there is room here too between the multiple perspectives for the viewer to see it all in yet another way. For this viewer, the presence and representation of women in Kenan, and therefore Sahar’s, work feels very reductive and stereotypical of an antiquated, male-dominant world view. Women are either absent, or sexual objects – true to the era and the characters represented, yet deserving of comment nonetheless. Kenan’s novel has been praised as a call for dialogue and reconciliation between Jewish Israelis and Arab Palestinians, although there is certainly a call and demand, I am still waiting for dialogue and reconciliation of Israeli culture with women.

Seeing the performance at the Nahmani Theatre in Tel Aviv, a place that has its own history and associations, as one enters one sees an empty stage lined with a row of white buckets on both sides. Sahar, dressed in black as is the custom of puppeteers and stage hands, enters the space, his expression serious. He looks directly at the audience and gives a small, yet definite nod, then takes up a bucket and pours salt onto the center of the stage. Music enters this near silence, and soon the voice of Rona Kenan, singer/songwriter daughter of Amos Kenan, begins to sing this old song in her distinctive voice, a voice which is so much of this moment in time. The song runs like a refrain throughout: “the way to the Kvutza (literally – group, or community) is not short, nor is it long.”

The other performers come on and all carry buckets from the sidelines and pour the salt onto the stage. The physical presence, the mass and heft of the salt, and its manipulation by the performers is as much a part of this story as the narrative. In their movements there is a sense of rhythm and ritual, an echo of the worker-pioneers of the Socialist-Zionist dream. Salt has had a symbolic presence in many world cultures, its preservative attributes encompassing life and death. In Judaism it is present in the Bible, from the warning of Lot’s wife to the practice of putting salt on sacrificial offerings, or rubbing it on a newborn to ensure that the child would grow to be a person of integrity. The phrase “salt of the earth” referring to the disciples of Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5:13), has become part of Israeli culture as well, denoting those who are deemed dependable and worthy, those worker-soldiers, Jewish pioneers who established and built this country.

The nameless narrator, represented by the faceless puppet, declares himself as one of those known as “the salt of the earth.” What meaning does this phrase hold today, what response does it evoke in the listener? Who is this narrator and how is he shaped and changed over the course of this journey and those he encounters on the way? The Road to Ein Harod is an emotionally charged, suspenseful experience, it’s taut, concise phrasing and evocative imagery and multiple focal points open questions in the mind of the viewer, questions that remain open for thought and discussion even when the performance has come to an end.

Performances: July 2nd at Warehouse 2, Jaffa Port, 20:30. This will be a performance in English. Tickets and additional info on the Hazira website.

The Road to Ein Harod/Salt of the Earth

Directed by Zvi Sahar, Puppet Cinema; Singer: Rona Kenan; In collaboration with Dramaturge, Development Crew: Oded Littman; Designer & Cinematographer, Performer, Development Crew: Aya Zaiger; Puppeteer & Performer, Development Crew: Michal Vaknin; Puppeteer & Performer: Yuval Fingerman; Puppeteer & Performer: Shai Egozi; Music and Sound Effects: Gai Sherf; Singer: Rona Kenan; Light Design: Adi Shimrony; Puppets by: Eti Sahar, Zvi Sahahr, Aya Zaiger & Robin Frohardt; Puppetry Consultation: Jessica Scott; Produced by Hazira Performance Art Arena.