The biblical phrase “Eat drink and be merry for tomorrow we die” comes to mind when viewing Shachar Marcus‘ eye-catching video Salt Dinner, a key work in a trio of new exhibitions presented under the umbrella title Changing Perspectives. The Dead Sea is the setting for this film in which Marcus and Turkish-German performance artist Nezajet Ekici struggle to keep a dining table upright while they gulp down wine (and salt) and guzzle on watermelon and grapes. When the waters get too choppy, the couple abandons the table to its fate and make for land. Here fantasy is combined with an existential threat.

This dual concept is a feature of many of the works found in the exhibition featuring solo shows – paintings, photos or prints – by established Israeli artists. Here it quickly becomes apparent that realistic imagery or art with a social or political message is not on their agenda. Instead, these artists cope with the tensions of everyday life in Israel by escaping from reality into a world of their own making.

Landscapes play a prominent part in this exhibition. But the way they are rendered is far removed from the gentle pastoral canvases produced at mid 20th century by Eretz Israel artists like Gutman and Rubin. Instead there is often in underlying thread of melancholy, or intimations of horror. Anat Betzer paints views of wooded areas and forests where the tall trunks of trees and dark foliage block out our view of a lighted area beyond. Such imagery turns the mind to such topics as the Teutonic worship of trees, and to the forests of the Holocaust where Jews were brought for massacre.

Another example of this altered perception is found in Ronen Siman-Tov‘s mysterious canvases from his The Surveyors series in which barren landscapes sectioning the earth from the sky are the backcloth for a few lone figures; a family with a child, and the figure of a man who appears to have paused in the act of digging a grave. In all these pictures, the people look up to the sky or backwards to a horizon that appears on fire, or filled with smoke. Has a disaster already occurred, or is it yet to come?

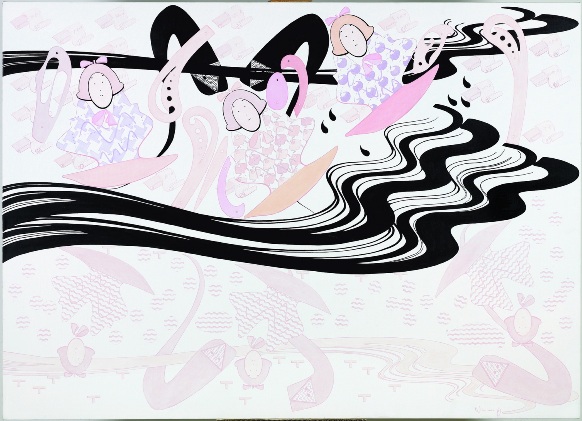

A light-hearted spirit emanates from fantasy paintings by Nurit David, an artist known for integrating different styles into her work and a thematic vocabulary fueled by a deep knowledge of history and foreign cultures, especially of the Far East. The series on exhibit here Two Cities, The Same Island illustrates the flat, reductive style of painting that she has recently adopted, the witty piece Sea for Girls being a fine example. According to my interpretation, this painting depicts a flotilla of small boats manned by Japanese ladies approaching the Tel Aviv coastline.

In contrast, works in an exhibition by young Israelis living in New York illustrate that most of the participants deal with reality and, despite being out of the country are continuously engaged with life here. I found this to be disappointing since I had assumed that having the opportunity to live and work in the Big Apple would have led them to fresh subject matter and new ideas. Indeed only two works hold one’s attention, both are video pieces: Noa Charuvi‘s recollections of the army effectively expressed through flickering black and white images of night manoeuvers; and Eli Barak‘s captivating project Big Cloud that follows the progress of a man touring Jerusalem dressed up as a Native American chieftain. This piece has visual appeal as well as raising questions regarding diversity and belonging.

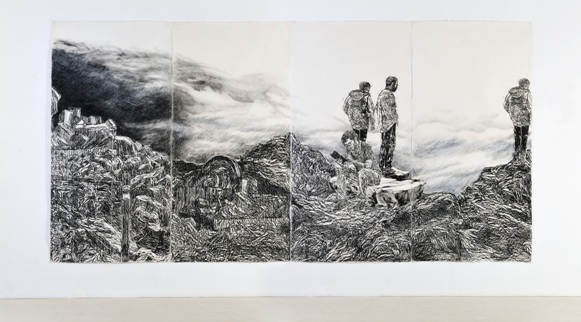

Another perception of landscape is proposed in Epoch of Space, the third exhibition on display. It relates to the Sublime – previously defined as the feelings of wonder and awe evoked by looking at, or exploring, the magnificence of Nature. As illustrated through the work of eight fine artists the meaning of this concept has altered completely. Nature is no longer conceived as something awesome and noble, but instead may well evoke feelings of anxiety or disquiet. Take Orit Hofshi‘s powerful woodcuts as an example. To some extent the scenes she creates recall ‘sublime’ views of mountains and water produced in the 19th century by German romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich among others. But the young people Hofshi depicts, having attained the top of some mountain ridge, find that they are looking out into space, into nothingness. As for the mountain, the uneven blocks of wood that Hofshi has gorged out to form its body may be likened, with a little imagination, to structures that have been abandoned or destroyed.

Overall, this is an ambitious project overflowing with fascinating items. In fact there is far too much material to absorb and appreciate in the course of a single visit to the Museum.

Haifa Museum of Art, 26 Shabtai Levy St., Haifa

Link to museum website

Excellent article, very well written.

Comments are closed.