What is going on outside this very room that I do not want to know? That is the question I ask myself as I write. The best theatre rivets us to our seats, but perhaps it can and should also make us want to bolt. Watching New World Order, three short plays by Harold Pinter (1930 – 2008), translated into Hebrew by Avraham Oz, adapted and directed by Gita Munte at the Khan Theatre, I couldn’t help but wonder: what am I doing sitting in the theatre when there is so much work to be done in this world.

Brilliantly directed, designed and performed, New World Order exerts a profound political impact because it takes us where we might not willingly go otherwise, creating a space where the familiar merges with the fantastic, evoking an almost spell-binding horror of self-recognition. Gita Munte, a talented and experienced actress making her directorial debut, has taken three of Pinter’s short political plays, and transformed them into a powerful play, unified by a shared vision. The transitions are seamless, watching the play one feels as though the three works – New World Order, One for the Road, and Party Time, were meant to come together.

Inside, there is a party going on. The music plays, the bar is well-stocked and the elaborately dressed guests try to convince their host to join an exclusive club. Outside there are check posts and the ominous sounds of sirens and helicopters, but these are merely viewed as annoying inconveniences and interruptions. No one really wants to know what is going on outside. Between chatting about the club and dancing, the gracious host finds time to interrogate and terrorize a family of three, detained for obscure offenses.

Pinter’s dialogue is minimalist and allusive, employing familiar and often clichéd phrases in bizarre contexts, menacing in its vagueness. This suggestive minimalism is reflected in Polina Adamov’s stage design. Metal framed glass partitions merge with the stone arches of the Khan theatre in combination with the lighting, designed by Roni Cohen, evoking the sense of utterly different environments according to the scene, from an opulent party to a basement torture chamber. Yet one retains the awareness that it all takes place in the same location, creating the feeling that perhaps the party is not so distant from the dungeon after all, perhaps the two are inevitably connected.

The costumes designed by Adamov are suggestive of wealth yet deliberately distanced from realism by an over-abundance of detail, and extravagant yet unusual combinations of styles. The effect is at once aesthetically pleasing and jarring. With her turban, cane, ruffles and stripes in bold black and white, Melissa (Shimrit Lustig) is the image of the culture of excess. Dusty (Carmit Mesilati Kaplan), in a silky print from head to toe – even her long boots are silk – is reminiscent of a flapper from the roaring twenties, but perhaps from a parallel universe. Over the course of the play, the green leafy print of her costume reminds me of camouflage, her silk hat, a helmet. The social arena is a war zone.

New World Order is performed by the actors of the Khan ensemble, who demonstrate once more their ability to be deliciously entertaining while conveying a serious message. Their agility of expression is conveyed in every gesture and intonation. The smile that plays upon the lips, and the tension seething within, easy to recognize as the split one experiences all too often between public life and private thoughts and feelings.

They play with the dialogue with an ease and grace, dancing with the words, exposing the narcissistic, opportunistic nature of their culture, in which words and the values they represent are distorted to the point where they are devoid of meaning. The meaningful questions, the ones that matter, are the ones that are not answered; the ones that should not be voiced, yet the hapless Dusty cannot help but ask: “What happened to my brother Jimmy?”

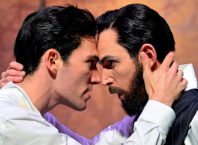

As a viewer, I was happy to cavort with the actors in the party scenes, laugh at the elegant parody of contemporary social life. But beneath the dance floor is the basement, where the prisoner is held, blindfolded. His captors and interrogators are the partygoers – this connection is the genius of the production. Terry (Yossi Eini) and Fred (Vitali Friedland) talk around the silent figure of the seated prisoner, with the same charm and refined manner they display at the party:

He has little idea of what we might do to him.

Well, he’s probably got some idea. After all, he reads the papers.

Interrogated by the host, Nickolas (Liron Baraness), who makes cynical use of a handsome demeanor and social niceties to intimidate his prisoner, Victor (Yoav Hyman) is the victim of this elaborate culture of deceit. Without the benefit of status, freedom or ultimately, even words, Victor makes no attempt to conceal his feelings. Fear, revulsion, horror and sorrow reveal themselves in the slightest gesture of his muscles, the force of his gaze. In his unrelenting honesty, the victim is also the victor.

Verbal jousting and innuendo reign in the parlor, the basement prison exposes the truth, and poetry is reserved for that which we can only imagine, which no witness can describe. Jimmy, in his absence, is a constant presence in the play, ultimately given voice by Vitali Freidland with haunting beauty and sorrow. There is no message of comfort from beyond, just the simple details of absence: “I see nothing, nothing, forever.” There is no way to redeem this death.

New World Order is a chilling portrait of who we are as individuals and as a society and at the same time, a stunning example of what theatre at its finest can be.

What is going on outside this room? Well, I probably have some idea; after all, I read the papers.

Future performances:

May 24 at 21:30, ZOA House, 1 Daniel Frisch Street, Tel Aviv

June 17 & 19, Khan Theatre, 2 David Remez Street, Jerusalem

Tickets and information: 02-6710281, www.khan.co.il

AYELET DEKEL