Was the German-Jewish artist Jakob Steinhardt a prophet? This is one of the questions raised in Jakob’s Dream, a new exhibition at the Israel Museum celebrating a magnificent gift of paintings, drawings, prints and illustrations from the artist’s estate, courtesy of his daughter Josefa Steinhardt Bar-On and grandsons Yuval and Eldad.

With the Museum’s total holdings brought to more than 800 pieces, curator Ronit Sorek had an extensive repository from which to make this commendable 80 piece selection that effectively illustrates, among other topics, Steinhardt’s visionary interpretation of modern Jewish history. Wisely, Sorek chose not to display Steinhardt’s large sentimental canvases replete with Rubenesque figures; images that have caused some critics to negate his skills as a painter and regard him solely as a master of graphic arts.

Born 1887 in Zerkow (formerly Germany) into an Orthodox Jewish family, Steinhardt studied in Berlin under two distinguished artists Lovis Corinth and Hermann Struck. Travels in Italy and France followed. And then, in 1912, back in Berlin, he co-founded an expressionist movement known as the Pathetiker (the Passionate Ones) whose members produced paintings and prints of an emotional nature that warned of impending catastrophe. But, as Ziva Amishai-Maisel points out in her erudite catalog text, Steinhardt, unlike his colleague, the German-Jewish artist Ludwig Meidner, did not actually depict war, but ‘suggested conflict through natural disasters, and by using biblical figures as metaphors for modern life’.

Apocalyptic Landscape is an outstanding example: a fiery sky, a burnt, leafless tree, dead bodies lying amid the ruins of a city or civilization – Steinhardt rendered this painting in a mixture of styles that befitted a young artist still searching for his artistic identity. One notes, for example, the fragmented building blocks of Cubism and the elongated figures that merge with their surroundings (El Greco and Futurism). And then there is the violent atmosphere that recalls the paintings of the Die Brücke, another group of German expressionists whose achievements included the revival of the woodcut, a medium they found – as Steinhardt did – to be super effective in the transmission of socio-political messages.

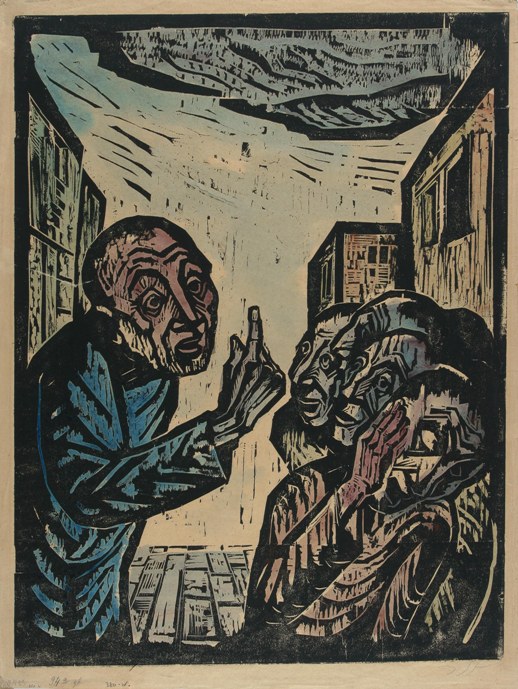

Steinhardt identified with the prophets of the bible, viewing himself as a lone voice ‘crying out in the wilderness.’ He produced many scenes featuring either an anonymous figure, or detailing the travails of a specific prophet. Jonah is the subject of several works on display, each focusing on a different episode in his story. While it is popular knowledge that Jonah was saved from drowning by a giant fish, his original mission, albeit reluctantly carried out, is less well known: God had ordered him to preach repentance to the people of Nineveh, known for their luxurious but dissipated way of life. In one of the woodcuts on display, Jonah addresses a group of people while pointing a finger up to Heaven. Steinhardt executed this woodcut long after the Pathetiker group had disbanded, yet the moral message is the very same. And once again, Steinhardt takes on the role of a prophet predicting the coming of doom and destruction on an errant society.

Although Steinhardt came from an orthodox home, his years of study in Berlin and Europe had taken him far away from his religious roots. But during World War 1, as a soldier in the Germany army and stationed in Lithuania, he had the opportunity to visit and befriend the Jews of the shtetl, learning to admire their unwavering faith despite the poverty and hardship of their lives. In 1918 he described his feelings (quoted in a catalog text) “(They) are the inner expression of the soul of my people and the most genuine expression of myself.”

After the war, returning to Berlin, Steinhardt continued to produce work on Biblical themes, many warning of future disaster, others expressing his wish for peace in a turbulent world. It was then, that he also began to paint and etch scenes of Jewish life based on what he had seen and experienced in Jewish Lithuania. It was as if he knew that this cloistered world would soon vanish for ever and he needed to document its character before it was too late. Unlike his prophet series that focused on a single person, the scenes that Steinhardt now produced illustrated the unchanging tenor of communal life. A typical piece is the dry point Return from Synagogue where a line of figures, bundled up from the cold, are making their way back to their modest homes; a scene also taken up in another work on view, a large oil painting of Jews trudging in the snow to Selichot prayers.

Steinhardt was a well established artist and illustrator in Berlin prior to the Nazis coming to power. But in 1933, after interrogation by the police, he took fright and speedily immigrated to Palestine with his wife and daughter. Settling in Jerusalem, he taught at the Bezalel School of Arts and Crafts, eventually, in 1953, becoming its director. There, and at the Studio School that he also directed, he passed on his knowledge and skills to several generations of young artists, in particular, professionalizing the art of printmaking in this country.

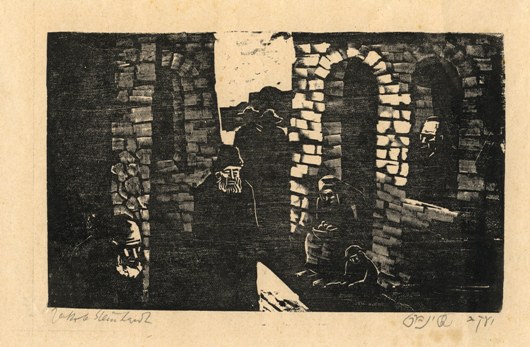

Among the many excellent works on display in this exhibition dating from Steinhardt’s early years in Eretz Israel, are woodcuts and wood engravings of the streets and alleyways of old Jerusalem. With figures and shapes rendered in sharp black and white contrasts, these somber compositions are almost identical with those that Steinhardt made of the Eastern European shtetl.

Steinhardt reacted strongly through his art to events that took place in Europe during World War 11. From 1947, for instance, comes a striking print of refugees huddling together in a small boat; while a set of grotesque images were part of his anguished response on learning about the full enormity of the Holocaust.

On the other hand, he ignored many local events; and when he did react it was not in the expected way. On view, for instance, are excerpts from his Elegies of War, an album of hand-colored woodcuts published in 1967 by the Bineth gallery, Jerusalem. The country was then rejoicing after the victory of the Six Day War, but Steinhardt chose to focus only on the horrors of battle. One print in this series depicts the silhouettes of two menacing creatures, the Ravenous Beasts, whose presence according to Isaiah (35: 1-9) will not be countenanced when redemption comes and “the desert shall rejoice, and blossom as the rose.” A fine exhibition leaving the visitor with plenty of material to mull over and remember.

Jakob’s Dream, on display at the Israel Museum until 5th March 2011, is located n the Robert and Rena (Fisch) Lewin Gallery, Hildegard and Simon Rothschild (Switzerland) Foundation Gallery, Edmond and Lily Safra Fine Arts Wing

ANGELA LEVINE

My oh my dude It’s the best the idea web site. It will be the brand new We noticed it still I Liked it.. Definitely will be back, you made a great deal of content in here 😀 ok back to do the job immediately 🙂

more so than Guernica?

Comments are closed.