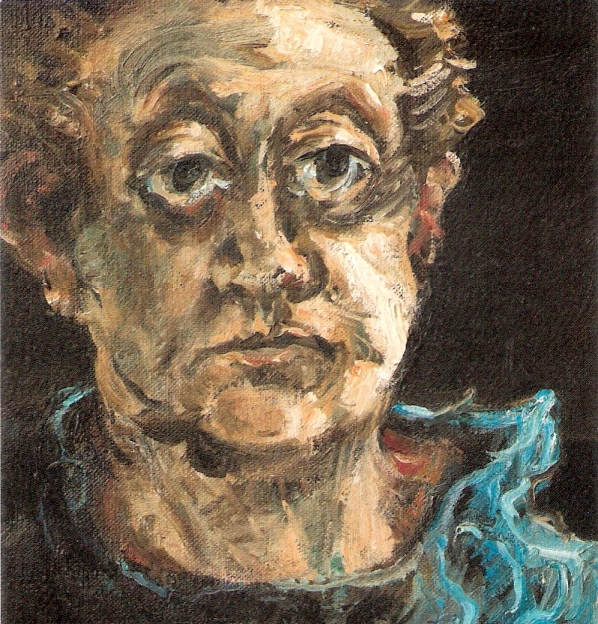

Yosl Bergner, one of Israel’s best loved artists, is celebrating his 90th birthday. To mark this event Tel Aviv Museum, which hosted a retrospective of his paintings 11 years ago, has mounted a small exhibition of one facet of his lifework: 22 examples of drawings he made in the 1950s illustrating the stories of Jewish-Czech novelist Franz Kafka.

As a child Bergner was already familiar with Kafka’s name and reputation since his father, the poet and writer Melech Ravitch, translated some of Kafka stories into Yiddish. In fact, when Ravitch translated The Trial in 1926, it was his son’s illustrations that accompanied the text.

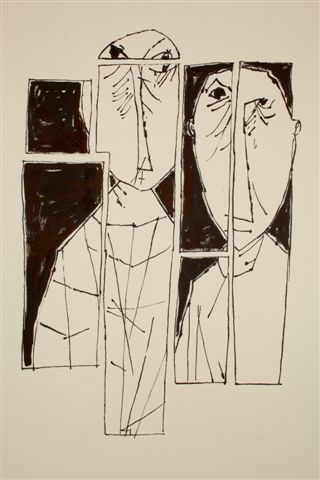

Bergner’s illustrations – a few in pencil, but most in pen and ink -are composed of thin lines skimming across white spaces to form weightless and shadowless figures whose hold on life seems fleeting and tenuous. The scenes he created exactly pinpoint the essence of Kafka’s world which is both real and dreamlike, populated by individuals suffering from anxieties and isolation.

In general, these drawings are not direct representations of events in Kafka’s stories, but are only inspired by them. For instance, in Metamorphosis, one of Kafka’s most famous short stories, a travelling salesman Gregor Samsa wakes up one morning to find himself transformed into a monstrous insect. Elsewhere in the same story, hearing his sister Greta playing the violin in another room, Samsa creeps out of bed. But Bergner – as illustrated in the drawing above – combines these two events into one scene: depicting Greta playing her fiddle alongside the cockroach-like body stretched out on the bed.

Bergner, who was born in Vienna but spent his childhood in Warsaw, must have become personally acquainted with some of the dark themes of Kafka’ stories. In the mid 1930s, his family left Europe to find a safe haven in Australia, obliged to start new lives in a strange country. (And it was there, moved by the plight of the poor and the harsh treatment meted out to the Aboriginal people, Bergner began painting socially relevant subject matter.)

In 1950, he and his wife Audrey settled in Israel, living for the first seven years in Safed. Here, they witnessed the arrival of new immigrants, cut off from their previous lives and beset with fears for the future; surely, a Kafkaesque theme.

With this background information, one can link up some of the images in the Kafka illustrations to the paintings that Bergner made at that time and later. For instance, his drawing for Kafka’s The Trial of two people looking through a window recalls the many paintings that Bergner produced showing faces peeping out of windows, or ‘locked’ behind bars.

Since the 1950s, Bergner has produced scores of paintings on different subjects and themes, and also designed for the theater. Like Kafka’s writings, there is a strong theatrical dimension to his work, notable also in these drawings. For example, the buildings he drew for Kafka’s Castle could have been a sketch for a stage set; the outline of tumbled down houses representing the East European shtetl.

It is here in these illustrations, to be followed by hundreds of beautiful paintings on a diversity of themes, that one notes the first appearance of Bergner’s signature images such as featureless faces with black holes for eyes; or the thick-beaked birds that swarm around his illustration to Kafka’s Castle. This avian motif will surface repeatedly in his later paintings: as butterflies symbolizing the illusions of the pioneers of Zichron Ya’acov; as vultures flying across empty halls of the synagogue in Toledo; and as bird –headed men featured in a series inspired by a 14th century Haggadah.

This little show, curated by Alisa Padovano-Frieman would definitely have been enriched if examples of the ‘Kafka paintings’ that Bergner produced during the 1970s and ’80s had been shown alongside these drawings. However, this exclusively graphic presentation still proves to be a touching homage to a great artist.

WHO WERE THE MAJOR SCULPTORS OF THE MODERN ERA? The answer is largely given in the Tel Aviv Museum’s current outing of the Helene and Zygfryd Wolloch Collection, donated to the Museum in 1997. This intimate collection reflecting the tastes of its collectors was originally located in the Wolloch home and grounds in Scarsdale, New York.

While some 20 international artists are represented, the focus is mainly on figural sculpture and its evolution in the 20th century from realistic forms to abstract constructions. A few of the exhibits do not fit into this category. For instance, the Italian sculptor Arnaldo Pomodoro is represented by a central motif in his work: a polished bronze sphere (1985) split open to reveal intricate jagged patterns; and Alexander Calder, by a typical spidery mobile, a ‘four-dimensional drawing’ hanging from the ceiling but which, unlike most of his sculptures, is painted black.

Here are a just three highlights from among the many outstanding figure- based pieces on exhibit:

The Dancer is by the Ukrainian born artist Chana Orloff who immigrated with her family to Eretz Israel in 1905. Five years later she moved permanently to Paris where she was one of the very few women who were part of the Montparnasse circle of artists and poets. While this particular figure was conceived in the spirit of cubism, Orloff substituted the sharp lines and planes of this style with the soft, fluid shapes that characterized the paintings of Modigliani who was a close friend. The dancer’s face lacks identifying features, Orloff opting to focus on the abstract concept of feminity.

The theme of the horse and rider made its appearance in Marino Marini’s work in the 1930s, with the animal in docile poses that recall his Italian heritage and the great equestrian statues of the Renaissance. The rider was at that time depicted as being in sufficient control to strike showy poses. But from 1945 onwards, Marini’s rider and figure groups became tragic symbols. The rider collapses or, as here, is impaled on the ‘horns’ of the horse. White stains splattered over the sculpture’s surface by means of chemicals after it was cast, suggest corrosion or decay.

The reclining figure of a woman was a major theme in the work of Moore. The late Erich Neumann, student of Jung, interpreted Moore’s depictions of the ‘great mother’ as a secular substitute for the primeval goddesses of earth, nature and life.

In this piece, as in others, Moore conveys the idea of fruitfulness through focusing attention on the wide pelvis and breasts of the figure, with the head sculpted small. The title of this piece indicated that Moore was considering the possibility of producing this piece in a monumental size, a project that was never realized.

The Bergner illustrations and the Wollach collection of sculptures are on view for three months.

ANGELA LEVINE