The current exhibition of drawings, paintings and sculpture by Sharon Poliakine, head of the Art Department at Haifa University and recipient of the 2010 Rappaport Prize for an established Israeli artist, is the most distinctive to be mounted at the Tel Aviv Museum this season.

Intricate drawings are an outstanding feature of her work; her expertise in controlling the quality and character of her lines stemming from the experience she obtained as a master printer at the Jerusalem Print Workshop for 18 years. She is now, and this is a rare phenomenon, an artist whose paintings and drawings take inspiration from printmaking.

To obtain these sinuous lines that give the appearance of having been ‘etched’ over smooth or roughened layers of color, she uses a home-made tool: a plastic bag with a hole cut in one corner, through which she squirts out black paint. These lines are either in the form of fine tracery or sturdy and wiry. In general, the shapes they produce hover between the abstract and figurative plus a few readily identifiable images, such as a hand, a bird, a garland of flowers.

Discarded objects lying about her studio – – pencils and brushes, rags, pots, string and bits of wood, and, most especially, spent tubes of paint– are a prime source of imagery in her work fashioned into small wall sculptures or surfacing in her drawings amongst a welter of abstract lines. A fine example is the ‘still life’ ink drawing shown above in which tubes of paint lashed together with cord suggest human figures.

In a number of her works, Poliakine pays homage to great artists. In appropriating the cyclamen plant as one of her consistent images in her drawings, she is paying her respect to Israeli artist Moshe Gershuni. But where his full blown cyclamens are a metaphor for tragedy or loss, Poliakine’s drooping flowers are rather an expression of the passage of time, and the grace of unfettered nature.

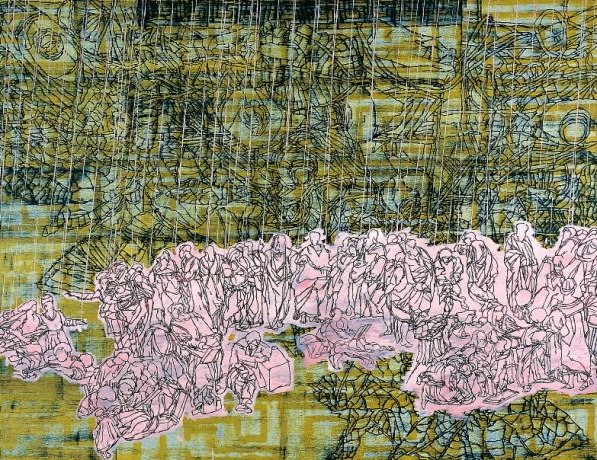

Many modern artists have paid tribute to the old Masters, but their ‘take’ on well- known paintings has generally been concerned with stylistic transformations. For instance, Picasso’s homage to Velasquez’s Maids of Honor simply entailed the reordering of this iconic painting into a cubist work of art. It is thus both surprising and remarkable that Poliakine’s has succeeded in enriching the theme of Raphael’s masterpiece The School of Athens, a work of art praising Classical knowledge and learning.

Commissioned in 1509 to adorn Pope Julius II’s private rooms in the Vatican, this famous group portrait features the great philosophers of the past. Aristotle and Plato and 56 other figures are depicted standing or sitting in front of a majestic classical façade. In Poliakine’s version, she has split this scene into two paintings. One is patterned with drawings of flowers with the position of the archway in Raphael’s paintings merely indicated by red dots. For the other, more complex painting The School of Athens I (shown above), Poliakine has excised all the figures from the original scene to set them down in linear outline in a pink cloud. Behind, she has painted in fragments of the marble flooring as seen in Raphael’s picture, together with intricate drawings of plants. The new and complex vista she creates is a virtuoso feat of draughtmanship but, equally important, it takes Raphael’s painting to another level, where learning and culture meet up with the beauty of nature.

A similar thematic bonding is achieved in another large painting in the form of a diptych, given the rather nonsensical English title Ignorant Fields (this is also the name of the exhibition). Fortunately, in Hebrew the combination of these words makes better sense, since the word bor can also mean ‘uncultivated.’

At first viewing, this large work appears to depict a furrowed landscape in deep perspective, with trees staked out at regular intervals. But, apparently this is not so. As curator Tali Tamir explains in her catalog text, this painting is based on a 19th century etching of the interior of a textile factory. In Poliakine’s version, this space emptied of the weavers has merged with an uncultivated landscape. Only the looms, as symbols of technology, remain; while the field, together with the pumpkin introduced into the picture, stands for the idea of agricultural labor.

Typical of a Poliakine painting is the fact that her imagery or her themes lead one’s mind to the works of artists. In this case Van Gogh, who early in his career, living in the Dutch village Nuenen, was deeply concerned about the effect that the Industrial revolution was having on local cottage industries. As a result, his first drawings and paintings were of weavers laboring at home. They were followed by his masterpiece depicting peasants eating potatoes, another ‘lowly’ vegetable.

The pumpkin, the newest image in Poliakine’s repertoire, takes center stage in the only floor-based installation in this show where fifteen giant specimens, cast in aluminium, have been grouped together. Attached to their upper surfaces, or balanced on connecting struts, are visual references to art-making processes or to famous works of art. For example, placed on top of one pumpkin is a mock-up of Delacroix’s famous painting The Raft of the Medusa, with slivers of wood for the raft and a flag, and the figures of the abandoned sailors suggested by bent tubes of paint.

As in the diptych ‘Ignorant Field’, and in her reworking of Raphael’s School of Athens, Poliakine’s installation sets symbols of culture alongside nature, as symbolized by the humble pumpkin. It is this strict adherence central theme developed in imaginative directions that make this prizewinner’s exhibition so special.

OREN ELIAV (b. Israel 1975), recipient of the 2010 Rappaport Prize for a Young Painter is an artist of great promise. The 12 large, richly-colored canvases he shows in his exhibition Two Thousand and Eleven, curated by Varda Steinlauf, are beautifully painted, conjuring up another-world atmosphere. Fragments of wearing apparel from a past era – a ruff, a choker, a beaded cape – and half-obscured portraits of a man he calls The Listener emerging out of darkness in a vaporous light. Eliav also paints details of architecture, one of his most haunting images being that of the façade of some great building, perhaps a cathedral, depicted in a palette of black and dark green with slivers of light illuminating an arch or an ornament.

Unlike many younger generation artists, Eliav does not feel the need to comment on the here and now of living in this country. His focus is on the technicalities of his craft where he is already carving out an approach that is both original – and seductive.

Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 27 Shaul Hamelech Blvd.

ANGELA LEVINE

There are some interesting points in time in this article however I don’t know if I see all of them middle to heart. There’s some validity but I will take maintain opinion until I look into it further. Good article , thanks and we would like extra! Added to FeedBurner as nicely

Comments are closed.