The Mané-Katz Museum, a historical gem sited on Mount Carmel, has reopened its doors after a two-year period set aside for repairs and refurbishment. Once managed by a non- profit-making society, now integrated into the complex of Haifa’s Museums, it has been brought to life again, with a new staff headed by Svetlana Reingold, and an impressive inaugural exhibition The Jewish Heritage of Mané Katz, guest-curated by Irit Miller.

40 works are on view, mostly paintings, but also drawings and a few small bronzes. This selection is only a small part of the Museum’s extensive holdings that includes flower studies, portraits, landscapes, small figure sculptures, as well as the artist’s collection of Judaica. But the focus here is on Mané-Katz’ true life work: paintings based on his memories of Jewish life in the shtetl.

Born 1894 in the Ukrainian township of Kremenchug, Mané-Katz was raised in a family steeped in Hassidic traditions, attending Yeshiva before studying at the Vilna School of Arts. In 1913, he came to live and work in Paris, the city where he would spend most of his creative years. A prominent member of the Jewish School of Paris –comprising scores of artists from Central and Eastern Europe drawn in the first quarter of the 20th century to this hub of artistic life– he and Chagall were, surprisingly enough, almost alone in their desire to portray Jewish subject-matter.

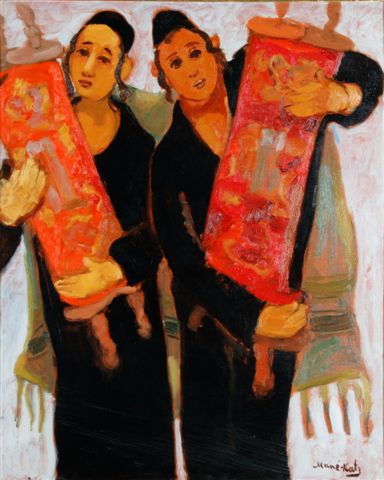

As the paintings of figures and scenes in the entrance and side galleries reveal, Mané- Katz’s viewpoint is somber and melancholy, contrasting sharply with the whimsical charm of Chagall’s folkloric renderings of Vitebsk. In Mané-Katz’s world, the grave figures of Rabbis and scholars appear on a shadowy, timeless stage, their forms described in thick brushstrokes and a dark palette, with bursts of vivid color – oranges, pinks and greens – illuminating a torah scroll, or a gown.

A sense of isolation pervades many works. As, for instance, in the joyless depiction of a wedding where the musicians and even the bride and groom are partitioned off from each other. The impression given here, as in so many of these paintings, is of a religious community on the cusp of vanishing. It is interesting to note that in 1940, five years after this work was painted, the German Jewish historian Leon Feuchtwanger prophesied that “the painter Mané-Katz has given to the ghetto an expression that will outlive the ghetto itself.”

Featured in the Museum’s long gallery are examples of the highly emotional paintings that Mané-Katz produced in reaction to news of the Holocaust. Among them is the unsympathetic picture The Slaughter, where the central image is the Christian Jesus, identified by skullcap on his head and the cruciform structure of this composition. Depicted in the torturously elongated style of Spanish painter El Greco, this figure extends his arms over twisted bodies sprawled on the ground. Conveying an equal anguish, are his ink drawings of distorted faces and figures that he produced in 1954 to illustrate Itzhak Katzenelson’s Song of the Murdered Jewish People.

Mané-Katz’s portrayals of life in pre-state Eretz Israel are in a quite different vein. Sentimental works in a range of exotic colors, they do not express reality – the hardship and struggles of a people fighting for their existence. In fact, the naivety of his approach, particularly evident in the canvas Am Israel Hai (Israel Lives On) evokes a certain hilarity today. Painted in 1938, it shows (on the viewer’s right) a group of sturdy pioneers. One holds a basket of oranges aloft, another a hoe or spade. A third figure wields a flag. In their midst is a bare-breasted maiden whose image appears to have been lifted from Delacroix’s painting Liberty leading the People. To the left, three Hassids in brilliantly colored garments, walk off in an opposite direction, seemingly averting their eyes from the charms of this buxom lady. At center-front, a child shades her eyes which are turned towards some distant vision.

One may wonder about the connection between Mané-Katz, the city of Haifa and a museum in his name. Here, in brief, is the story. From 1928 onwards the artist visited Eretz Israel many times; in particular showing his loyalty to the country in 1948, when, at the height of the War of Independence, he not only refused to cancel an exhibition of his works at the Tel Aviv Museum but shipped over 60 canvases, and came to the opening. In 1958 at the age of 64 he settled in Haifa, bequeathing his estate and the contents of his Paris home to this city on the understanding that the house and studio on Mount Carmel endowed to him by the Municipality would on his death be converted into a Museum. It is now truly satisfying to know, some 50 years after this promise was given, that the Museum is not only going strong but set to expand its activities by presenting “a picture of the world of culture and expression” as related to the life and times of Mané-Katz.

Mané-Katz: The Jewish Heritage opens on April 9th at 8.00 pm. It will remain on exhibit until the end of September.

Mané-Katz Museum, 89 Yafe Nof, Haifa. Tel. 04-8383482

ANGELA LEVINE