“Most of these things and people, you won’t see them,” said Yuval Yairi, indicating the images of construction workers, scaffolding, ladders, exposed walls and mounds of sand. Yairi was invited by the Israel Museum to observe and photograph during the museum’s three year renovation project, which culminated in the opening of the renewed Israel Museum on July 26, 2010. Yairi presents a selection of the photographs and video in “Work” – a solo exhibit at Zemack Contemporary Art (ZCA) in Tel Aviv, curated by Dr. Ketzia Alon. The artist discussed the project with Midnight East, which presents a different look at the museum, and a certain shift in focus for his own work.

Yairi’s previous work reveals the artist’s close connection to place and time; Forevermore and Palaces of Memory are also intimately related to Jerusalem. Seeing those works one is often struck by the sense of absence, places without people, spaces that in their details evoke the memory of the people who had been there, moments or years before. In the photographs and videos exhibited in Work, the people moving through this choreography of construction are a constant presence, drawing the eye and mind of the viewer. Yet one views the images knowing that when walking through the same spaces in the Israel Museum today – we will not encounter these workers.

“It’s a portrait of a temporary state, a tribute to the transient worker,” said Yairi, “They invited me to do the project and I came into a place that I could not recognize. [Yairi came into the Israel Museum about six months after the renovation had begun] All the spaces of the museum I am familiar with – suddenly there is nothing there. Everything is the opposite of a museum – dirty, full of dust, broken walls that allow light to enter from outside – the opposite of the sterility, permanence, and the feeling of the security that you feel in a museum. It is a capsule of culture –the museum is the palace of palaces of memory and that is why I was so intrigued to go there. But suddenly confronted with this chaos – it was hard to begin approach it. How do I relate to this place? I soon understood that there was no chance I could repeat the way I had observed and worked on previous projects – where I scanned and observed spaces slowly, one part at a time.”

“In those projects – I am stationary; standing on one spot and the scan of the space can take a day or a week. I work with a camera with a very narrow lens, full zoomed in. Each frame receives its attention with a big overlap between the frames. You need to be very organized not to miss a spot. Each point in space receives the same attention. There are places that I photographed empty, then put a chair down and shot again, layers upon layers, fragments of light and time.”

This method of working, as Yairi’s gaze takes the space apart, focusing on every detail, then reassembling the parts to create a new image, can be seen in works such as Rooftop from Palaces of Memory, which was exhibited at the Alon Segev Gallery in 2007, and the Andrea Meislin Gallery in 2008.

“I was a bit satiated after three projects and seven years working in this manner, and also – the place was a construction site! They had already started taking out the art work and broken all the walls. If I had considered working in this slow manner that can take a few days to cover a single space then there would have been places where the space would no longer exist if I returned to finish. Lots of workers, lots of movement of people…it took me a while…I said to Nissan Perez [Horace and Grace Goldsmith Senior Curator, Noel and Harriette Levine Department of Photography, Israel Museum] after walking around for a while – look, I don’t know …I connect to the simple actions and he said, ‘Do whatever you wish.’ And I said, listen, I’m not sure I want to do these photographic works, I want to create video works and he said: Go with it.”

“They [The Israel Museum] gave me complete freedom with respect to what I photograph and how I photograph and without any responsibility to the documentary element. Over time people became accustomed to seeing me there and saw me as a documenter because I am with a camera and kept saying: Oh you have to get this! And I said: I don’t have to do anything – even though at that moment they are installing Anish Kapoor on the level above and at the same time I am looking at the youth that I call “Nimrod.” It happened all the time, these conflicts between what is more important…especially as they progressed and the clock was ticking – May, June, July – many things were going on simultaneously and I wanted that simultaneity to be felt in the exhibit.”

“The freedom was given and I thank the museum very much both for the freedom of movement and the complete lack of censorship in terms of the places that they let me enter – the heart of the museum, and even things that might appear critical too and can be interpreted in different ways, not necessarily complimentary to the museum. I really appreciate and respect them for giving me that freedom and for not trying to manipulate or influence me. I was in the kishkes [Yiddish: guts] of this thing.”

Walking through the exhibit, Yairi pointed out the video Gridwork 2, saying, “This is the place where the Kentridge exhibit is now up and the light comes from outside. I only use available light. I have never lit anything. One thing I relied on, which disappeared as the renovation progressed, was the penetration of natural light. At this stage, it’s simply a construction site, and I use it in observation. Instead of covering the space in time to its length and breadth, I think through to its depth. I can stand for two or three hours watching an action and taking pictures from time to time… sometimes there is an action that I anticipate or look for and it reached a point that I would go crazy: why don’t the workers do the action that I want them to do?”

“I became a part of the museum…in the last year I was like a worker at the museum, I was there every morning,” Yairi said as we entered a separate room in the gallery where two larger scale videos are shown, “There’s the restoration department. I took these photos of the stone where it is inscribed: “Blessed shall you be in your comings and blessed shall you be in your goings.” (Deuteronomy 28:6; JPS translation of the Tanakh). This is at the entrance to the archaeology wing; it’s an action that took 6 hours. I didn’t know where it would lead and it almost looks staged, it’s a kind of theatre. It begins rather abstractly behind the nylon, two workers doing a sort of dance. Look at this section between the two men where they are preparing the pulley for lifting the stone that weighs 3 tons. It’s really abstract and as if it’s something violent, almost sexual, some kind of unclear ritual and slowly it is uncovered in stages with the unveiling of the nylon.”

“I began in one place and I spent several hours taking pictures of the preparations for lifting the stone – and that was where all the action took place, beyond the wall. Then I decided that it was all too noisy for me and I set up in the space where they were going to place this large stone and from that moment on – it’s no longer in my control. I decided on the frame and then things start to happen with lots of surprises. For a moment suddenly someone decides to open the nylon then changes his mind and closes it. All these things…imagine that this one action – just lifting the stone – took an hour.”

Yairi created the videos entirely from still photographs taken at the museum, set on a timeline with a dissolve effect between frames, working with Yoav Bezleli on the video editing. “This is not exactly video,” said Yairi, “because I wanted to remain on that hinge between stills and video, I wanted to remain faithful to stills photography and that is why I chose not to include sound in the exhibit space. It is very easy to add sound – what you hear in most exhibits – it’s a form of manipulation that penetrates in seconds and accomplishes things that the photographs alone cannot. That was a decision, not an easy one, because it is very tempting. This quiet that characterizes photography – you know when you look at a photograph it doesn’t play music for you, it’s a photograph.”

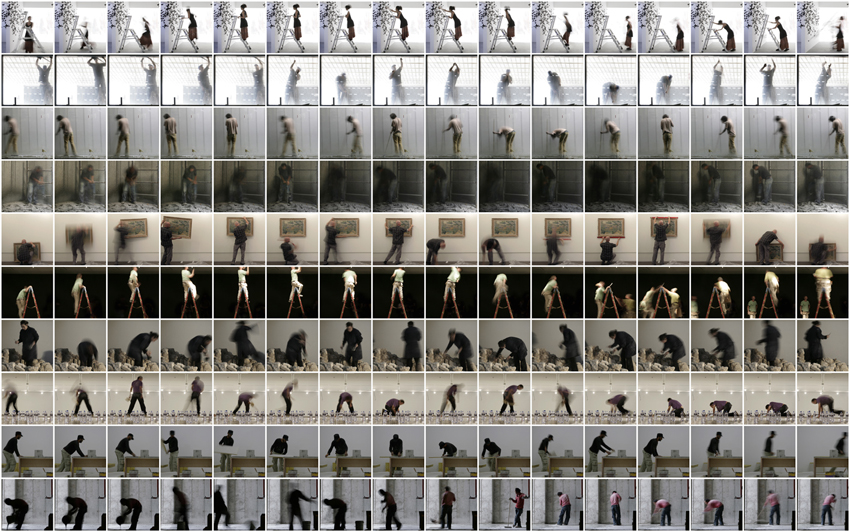

The videos were created through a process of editing and taking out frames until there are enough frames to convey the visual information. “I wanted to find the harmony,” said Yairi, “the dissolve creates an illusion of movement but there is no real information beyond the two stills. It was created through a choice and small changes from place to place that are almost imperceptible.” For Yairi, this sense of time is the “heart beat of the exhibit.” The Chronovation series, each composed of a grid of 160 images, conveys this sense of time in a different manner. “It’s a simultaneous positioning of many actions in one composition, which annuls the hierarchy between one form of work and another, said Yairi, “All workers receive the same importance – and that is similar to my previous works in which each part of the space receives the same attention.”

The focus on the workers suggests a certain critique, to which Yairi concurred, saying, “Yes, I also have some self-criticism – who am I? I spend all day taking pictures of people at work and come home in the evening and say ‘Oh, I’m so tired.’ I took pictures of people working, and it is hard to stand for 8 hours, but I have no defined role, I have no useful function in what I do. I can look for rationales and that is how I make my living…but there is a conflict with my humanistic and socialistic perspective when I’m talking to you in an art gallery in Kikar Hamedina.”

“There are some photographs where you feel compassion for the worker and there are some where you feel that he is a poet. The action is very poetic, very easy – he doesn’t even have to touch it and it becomes cement. It’s magic. So… I have criticism, beginning with myself and the amazing distance between the young man here and what is happening on the floor above. Yes, there is also criticism here, not of the museum specifically, at all, but it’s a phenomenon that represents things that are happening throughout the world. In the art world it really stands out – you see a work of art that costs 100 million dollars and there is a problem.”

This distance – between the lives of the workers and the privileged space in which they are working, between the rough look of the museum under construction and the clean lines of the renewed Israel Museum, between the buckets, ladders and scaffolding that fill many of the photographs, and the works of art that now occupy the same spaces in the museum – this distance and tension imbue the exhibit with a subversive force; itself in stark contrast to the often lyric feel of the photographs.

One of the images that embody this tension features Yitzhak Danziger’s statue Nimrod, which has an iconic place in Israel art history. Yairi said of this work, “I took photographs up until the day of the opening. I think the Nimrod Roundabout was a few hours before…there are two workers with a cleaning machine. It symbolizes those final hours of tension because there were already guests arriving …so it’s like a kind of clock and also a kind of ritual around the sculpture which is also a kind of…and it connected and it symbolizes for me everything that happened there – the worship of the temporary workers around the holy of holies.”

Yairi’s exhibit suggests equivalence between the different kinds of work: the construction work, the precise installation of art works in the final stages of the renovation, and by extension – the creation of these works of art. The act of observing and photographing the work and daily routine of the workers brings their narrative into the collective consciousness and preserves it within the context of the museum, perhaps challenging one’s consideration of that cultural construct. “There are different groups and each have their own lunch eating rituals. The Chinese sit on a board of Styrofoam and take out something they brought from home – some kind of noodles, sleep for half an hour on the Styrofoam and – tak! Get up and get back to work. The Arabs bring a toaster oven…and at the end of the day I’d make the rounds to see what traces remain, and this is classic,” said Yairi as he pointed to the remains of black coffee in a plastic cup, “it looks almost staged.”

Yairi attributes the dramatic sensibility of the photographs to “the fact that I am heavy and slow…well, I’m not so heavy, but I don’t dash about taking pictures. There is the tripod and the camera…if it is meant to be, it will happen. And there are many times when I miss something because of the way I work. By the time I set things up and arranged the level it was over…and I missed it…so, there will be something else…I believe I missed about 99% of what happened in the museum. But one percent is also enough.”

Yairi, passionate and precise in his work, recalled that he felt a need to create structure in his task of observation, he said, “I felt that I had to condense it, so that I will have rules – what is the core, what is the seed of the seed of all that I am doing here. I decided to try to put it into words, and arrived at four words: person, space, time, and light (in Hebrew these words have three letters each: אדם, חלל, זמן, אור ). This is the essence of the project; everything else originates from these words.”

Yuval Yairi – Work

The exhibit will be on display through June 10, 2011 at Zemack Contemporary Art, 68 Hey B-Iyar Street, Tel Aviv, +972 3 6915060. Opening hours: Sunday through Thursday from 9:30 to 20:30, Friday from 9:30 to 15:30.

Wow. I really enjoyed reading this blog.

It made me “see” the renovations as if I’d been there. I was excited by all changes that were taking place in front of your eyes.

Thank you so much.

Beautiful show and clever artist. (Loved the last paragraph with the 3 words..), thanks.

[…] 26 – Gallery talk with Yuval Yairi on his exhibit “Work” , 19:00 at the Zemack Gallery; New Olds Exhibit opens at the Design Museum Holon; Contact Combat, a […]

Yuval, your work is amazing…the thoughts behind the work make your photos hold extra special meanings besides being pleasurable to the eye. They get the brain working, also. Good luck, always, Joyce and Jim

Comments are closed.