As always, one of the great pleasures of a film festival is in the comparisons and contrasts one observes when two (or more) films that theoretically have very little in common are seen in close proximity. A great example is in the duo of Errol Morris’ Tabloid and Scott Goldstein’s Where I Stand: The Hank Greenspun Story. Both are biographical documentaries about fascinating characters whose life stories could conceivably span several different films. Where I Stand’s main character is so magnetic that it would seem a difficult story to mess up; Tabloid’s story is so utterly bizarre that probably no one in the world other than Errol Morris could have made a credible movie of it.

A conventional documentary about an almost absurdly prolific man, Where I Stand initially seems like a family’s loving tribute to a larger than life patriarch. Not terribly thrilling or relevant to the rest of us. As Anthony Hopkins narrates, Hank Greenspun’s life sounds like a lovely tale to tell at a Golden wedding anniversary, or a 75th birthday. Cocky, charming and extremely charismatic, the man proposed to his wife within minutes of meeting her (while in the US army in Northern Ireland), and on a whim moved his new family to Las Vegas to take some small part in the boom created by Bugsy Siegel’s inception of Las Vegas as we know it. The name dropping seems a bit crass, but I forgave the family for wanting its father’s story told.

Then other names get dropped. Frank Sinatra. Joe McCarthy. JFK. Ben-Gurion. Teddy Kollek. Shimon Peres (who is interviewed for the film). Jimmy Hoffa. Richard Nixon. Anwar Sadat. Menachem Begin. Howard Hughes. Like Forrest Gump, it becomes apparent that Hank Greenspun, not just his family’s pride, was involved in some of the most famous events of the mid-to-late 20th century, from Israeli Independence and the Red Scare to Watergate and the Camp David accords. He also took on fights from civil rights to environmentalism to IRS bashing, all while running outrageous and often incendiary editorials from the Las Vegas Sun, the newspaper he founded and published for 40 years.

The film itself is not particularly remarkable in its storytelling, but, then again, perhaps a traditional by-the-numbers documentary is exactly what a larger-than-life story requires, even if it means smoothing over and white-washing some of the thornier aspects of the man’s life. Little attempt is made at explaining the motives of a man who befriends and is supported by mobsters, at times uses mob tactics, yet takes part in crusading against the mobsters who controlled Vegas in the 60’s (while being assisted by Jimmy Hoffa). Or the crusader for righteousness whose method of fighting his vile enemies is by insinuating calls for murder and recommends suicide (though 60 years later, it’s hard to dislike anyone on Joe McCarthy’s enemies list).

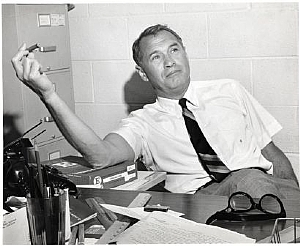

Morals aside, Greenspun’s magnetic presence is quite enthralling to behold. It’s saying something when Anthony Hopkins is narrating your autobiography and comes off as faint and untheatrical compared to you. The man –who passed away in 1989- looks like Edward G. Robinson and no less tough, and sounds like Mel Brooks with only slightly less alacrity and storytelling ability. He is eloquent and quick to laugh, and has seemingly never been introduced to modesty. He talks with great pride and a twinkle in his eye about his days of gun running with Teddy Kollek for the Hagannah (something he was convicted of, which prevented him from running for office until JFK pardoned him), and one senses a born showman in the editorials he published about anything he damned well pleased.

The more I think about him, the murkier his story appears to be, yet without a doubt, Hank Greenspun led a remarkable life, and for every grey element there is some great nobility and righteousness (he was instrumental in the desegregation of the Las Vegas strip). In the somewhat cloying final montage, family members, employees and friends speak great praise of him, when what appears to be the most concise epitaph is spoken by a former gunrunning comrade: The man was addicted to adrenaline. Hank Greenspun seems to have led about a dozen lives, and though not always commendable, his vitality is unbelievably enviable.

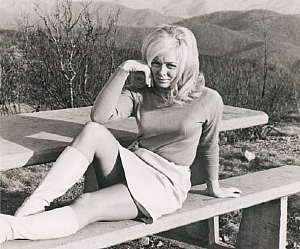

On the other extreme, there is Errol Morris’ Tabloid. There is absolutely nothing enviable about the life of Joyce McKinney. A former Miss Wyoming, McKinney made headlines in 1977, when she instigated what would come to be known as ‘The Mormon sex in chains case’. As Miss McKinney tells it, she was a pretty young girl looking for love, when she came upon Kirk Anderson, a tall, overweight missionary for the Church of the Latter Day Saints. They were engaged to be married, when Anderson disappeared off the face of the earth.

The heartbroken McKinney hired a private investigator to locate Anderson. This private investigator located Anderson in England, where he appeared to have been guilted and forced into joining a Mormon mission, and was well on his way to becoming a priest of the church. The undaunted McKinney put together a group of bodyguards and friends, and freed Anderson from the brainwashing he received at the church through compassion and unorthodox love-making.

Once freed from the shackles of the church, Anderson willingly went with McKinney to London, where he was once again abducted by the cultish Mormons, and was forced by his church and family to make up vicious lies about what had happened.

So much for McKinney’s side of the story. The other version of the story, the one that fuelled the British tabloids, is somewhat different in nature. This version has it that the demented and sexually deviant McKinney was infatuated with Anderson, scared him away, took hired thugs and emasculated sycophants who gradually abandoned her, once they realized her goals: to kidnap Anderson, rape him, become impregnated from him and marry him.

This bizarre and disturbing tale would hold enough morbid fascination in and of itself, but is only one of a number of tales this film has to tell.

When it broke, the story was so juicy that it immediately sparked a sensation, made something of a celebrity of McKinney and started a rather relentless quest by the tabloids to uncover as much of the sordid details as possible. Soon after skipping bail in England (by disguising herself as deaf-mute), McKinney sold her story exclusively to the Daily Mail, which painted McKinney as a love-struck romantic. This did not sit well with their competitor, The Daily Mirror, which uncovered a treasure trove of material the quite graphically dispelled the notion of McKinney as a poor damsel trying to free her lover from the evil cult that had abducted him. The circus that ensued is where the film got its title, but is still not the end of the story.

The last episode of the film is too surreal to even go into, and shows that whether or not Joyce McKinney was not entirely healthy and well-adjusted before the scandal, the ensuing sensation absolutely caused something to go amiss. This would be purely pathetic, us in the audience following Morris’ gaze in leering at this human freak-show….if not for the fact that throughout the entire film, Morris’ peerless interviewing skills keeps us utterly and shockingly aware of McKinney as a human being. And that is the most shocking and surreal thing about this film. The material this film is built on is not the archive material, but McKinney herself, being interviewed by Morris, guiding us through every step of her very public life.

Morris has a long history of giving people the chance to explain themselves in front of his camera, and often hang themselves in the process. McKinney might be his most pitiable subject to date. Initially, she seems like a bubbly old grandmother with a homey and slightly mischievous laugh. And, as we begin with her side of the story, this seems like it’s going to be an expose about the dangers of Mormonism. But as the story gradually peels away, it becomes more and more apparent that McKinney has been lying to us and deluding herself, the latter taking central stage as the story progresses. It is hard not to feel sad when watching a woman who is not evil or inherently mean or unkind absolutely demolish herself on screen, and seemingly utterly unaware of what on earth is wrong with her story.

So, in the end, Tabloid is not really about Tabloid journalism. Although, perhaps Morris’ most scathing and devilish addition to the story are the people he chooses to tell it. Two of the interviewees for the film are tabloid journalists- a writer for the Daily Mail and a photographer for the Daily Mirror. The photographer comes off only slightly less sleazy than one would imagine a Tabloid photographer, but the journalist for the Mail is the most sane person in the film, and the most clear-eyed. He is crass, but has sympathy for McKinney, and has a terrific sense of humor about the whole affair. It may just be me…but featuring a Tabloid Journalist -who is, at least theoretically, a loathsome creature to most of the audience- as the audience’s surrogate is one of the great sick jokes of this strange, uncomfortable, tantalizing and terrific film.