“French Connection” a panel discussion between French cartoonist Plantu, Israeli cartoonist Michel Kichka and Palestinian cartoonist Baha Boukhari took place at the Animix 2011 festival at the Tel Aviv Cinematheque on August 18, 2011, at the end of a day that had been marked by news broadcasts of the terror attacks in southern Israel. Introducing the panel, festival artistic director Nissim (Nusko) Hezkiyahu noted that is the first time that the Animix festival is hosting a cartoonist from Ramallah.

Political cartoonists are uniquely suited to create bridges in situations of conflict, positioned as they are between hard news and humor, text and visual expression; seeing a situation from more than one perspective is a defining aspect of their work. Politics tempered by empathy and a sense of the ridiculous, humor is their weapon and defense, usually allowing the cartoonist a greater measure of freedom within the newspaper. Baha, Kichka and Plantu are all members of the organization Cartooning for Peace, and have worked together in that context. Their long standing acquaintance with one another contributed to a warm and informal atmosphere, despite the inevitable barriers of language and politics. The three cartoonists sat together on the low stage with a laptop, showing their cartoons on the big screen while conversing about the images and related political issues.

As the local representative, Kichka hosted the event, and began by asking Baha to talk about his career path, which has taken him to Syria, Kuwait, and Tunisia before arriving at his current position as cartoonist for Al-Ayyam in Ramallah. Baha said that he began as an amateur in Syria and got his first big break in Kuwait. He made a cartoon for a newspaper there and as a result the newspaper was shut down. “Al Rai Al A’am heard about the crazy cartoonist,” said Baha and he then worked at Al Rai Al A’am for over twenty years. Kichka commented, “You told me that the newspaper closed down 17 times because of your cartoons,” and Baha shared several of those stories with the audience.

The conversation often focused on the issue of freedom of speech, its limits and interpretations in different countries. Referring to Baha’s work in Tunisia, Plantu said, “In Tunisia one is not allowed to draw against Ben Ali [Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, President of the Tunisian Republic 1987 – January, 2011].”

“Not Ben Ali and not another,” said Baha. He said that on arriving in Tunisia he was told at the newspaper that they want to take advantage of his experience to improve the look and layout. He worked with them on layout and was kept so busy that he eventually complained “I haven’t time to draw cartoons.” At that point, the underlying truth became apparent, and Baha told the audience, “They can’t mention very clearly [that one is] not allowed to draw cartoons in Tunisia.”

Baha said that he had experienced different forms of censorship in the past, in the form of creative editing. Talking about his five year sojourn at Al-Quds, Baha said “I used to draw with aquarel. When they scanned [the drawing] they feel free to change the caption. I finally quit.” Referring to his current affiliation with Al-Ayyam in Ramallah, Baha said, “Talking about margin of freedom, freedom of speech. They usually publish my cartoon as it is. They rarely remove the caption, but don’t put another thing.”

Many of the cartoons related to the “Arab Spring” and its implications:

Kichka described a cartoon showing demonstrators as saying, “We have shown how we can destroy tyranny…how can you build democracy?”

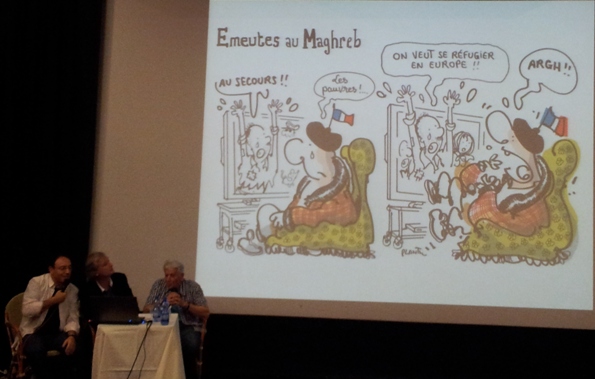

Every country and culture has its own taboos and part of the cartoonist’s task is to play with those limits to provoke thought and discussion. Looking at his cartoon of a French person watching news of the Arab Spring on television, feeling sympathy for the revolutionaries until they seek refuge on his turf, Plantu said, “It is not easy to print this cartoon in my newspaper. We have to prepare in Europe for the future and they don’t want to see this aspect. I am skeptical about the future of democracy in Arab nations.”

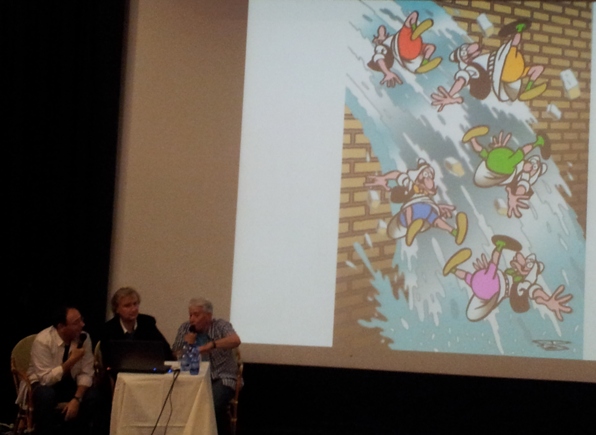

When Baha’s cartoon showing Arab leaders falling down a wall was shown, Plantu commented, “I think about you. In Ramallah, Palestine, your leader [looking at this cartoon] thinks: maybe he is thinking about us.”

Baha replied, “We are not a state yet. Where I work they understand the margin of freedom of speech. They give the journalists the right to criticize anything from their neighbors, but not locally.”

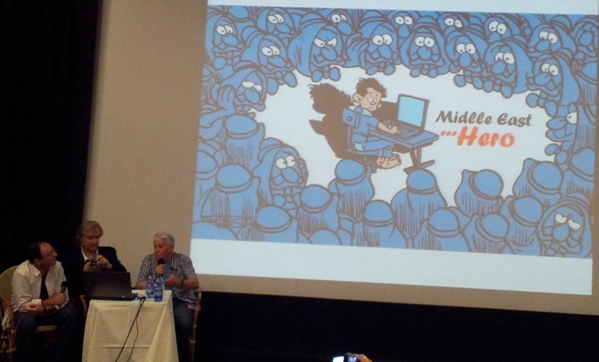

Speaking of cultural differences and taboos, Kichka commented on his cartoon depicting the internet’s role in revolution, “In America you cannot even make a cartoon with f…”

Referring to a cartoon in which he based the graphics on engravings in the style of the French Revolution era, Kichka commented, “In all revolutions there is an after revolution where the revolutionaries become also terrorists.” To which Plantu responded, “It is good for the debate.”

Despite the overall friendly atmosphere, there were some tense moments. One occurred when Kichka pointed out Plantu’s homage to cartoonist Naji al-Ali [a Palestinian cartoonists shot and killed in London on July 22, 1987], including the signature figure of Handala in the corner of a cartoon. The conversation inevitably veered to the difficulty of determining the responsibility for al-Ali’s killing. Why would anyone have an interest in assassinating a cartoonist – there are different versions of the story on the internet and elsewhere, some blame Arafat and some blame the Israeli Mossad. Kichka addressed the impossibility of knowing, saying “There is no truth.” Baha, a friend of al-Ali’s from their days in Kuwait, countered with the question, “Why was Ghassan Khanafani killed [by a car bomb in Beirut, 1972], if you can answer that question?” Kichka replied, “I can’t.”

Later, Baha described a cartoon showing a blue Star of David surrounded by flowering jasmine as the effect of the Arab Spring on Israel, prompting a member of the audience to ask, “The idea is that yasmin [jasmine in Hebrew] will destroy the shield of David? Plantu joined the conversation, pointing out that the Star of David in the cartoon is not destroyed, but does have some cracks. Plantu said, “It is good for debate. You can have 10 or 20 answers with a cartoon. Maybe one day all the revolutions will make trouble for Israel.” Suggesting that there are many possible underlying forces instigating the current revolutions and the uncertainty of the outcome, he said, “What is the real reason for all manifestation? They can win the war for fundamentalism…that is not a smiling future.”

Baha said, “As a Palestinian we are all looking for September. We are demanding our right to be free as a State. It’s time to implement [Oslo agreements]. We are not asking something impossible.”

Kichka responded, “It is not so simple. Today there were five terrorist attacks on Israel made by Hamas.”

Baha said, “I condemn them, nobody supports them.”

The discussion closed with comments on the Israeli “Rothschild Revolution.” Plantu said it is “sympathique, because it is without violence,” adding that it is good for those in Europe with anti-Semitic leanings to “understand everyone is not full of money.” In terms of the way Israel appears to the world, Plantu also said that the current three-way discussion presents a different aspect of Israel, saying, that people in France “cannot imagine it is so easy to have this debate with a friend from Palestine and a friend from Israel.”

“It was not so easy to bring Baha here,” Kichka replied, and said that he had help from the Peres Center for Peace in receiving the required permissions. Kichka and Baha then discussed a cartoon that the latter had drawn in relation to the “Rothschild Revolution.” Unfortunately, the cartoon was not available for view because Baha had hesitated to bring it with him. Kichka said, “Next time, don’t be afraid to bring your cartoons.”