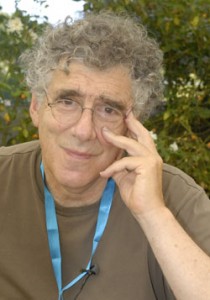

Elliott Gould comes to the interview in a brown T shirt, brown shorts, socks and sneakers. He smiles his famous half-smile as he eases himself into a chair. His eyes appear only partially open behind a pair of round, wire-rim eyeglasses, and his voice is soft and low. He appears to be totally relaxed, the very image of “calm.”

I, on the other hand, am sitting across from him in quiet turmoil. I have to interview this guy, and I am not quite sure I’m up for this. I have interviewed God-only-knows how many people in the past five years—some actually famous—but this is my first “legend,” my first “icon,” my first “star.” As if that weren’t enough, I have, so I’ve been firmly told, “exactly-one-half-hour-and-not-one-nanosecond-more” to ask a few questions of someone whose films and occasional TV work have entertained and inspired me since 1968.

Evidently reading my face like a film script, Gould leaps in and begins the interview by interviewing me. With videotape rolling, he is asking superbly probing questions about me, my marriage, my wife, my kids, my educational background—even about the tattoos on my arms. The damn thing about this is that he seems not only genuinely interested but focused. As the ticking of my cheap Seiko wristwatch seems to become louder than my voice, I am aware that, sooner or later, I have to somehow gently change the focus of conversation from me to him. It isn’t easy. As he continues to ask me about me, he is engrossed and amused by the fact that my wife is Filipino, a convert to Judaism, and far more religiously observant than I am.

Before long, this segues into a discussion of Jewish identity, and I am now talking to Elliott Gould about Elliott Gould. He says, “I have very deep roots. I don’t deny my roots. I was brought up as a Jew and always will be a Jew. I consider myself to be unorthodox. I work with some orthodox people. In recent years I was asked by the New York Jewish Theater to consider doing a staged reading of a play called Mea Shearim, and to play the ultra-orthodox Jewish rebbe. I learned a lot. I learned that there’s so much more to learn for someone like me—someone who is not orthodox and who was brought up…you know, people who go to shul only on the High Holidays. But I’m one of ‘us.’ And I am the way I am, and I don’t deny it.”

I then note that he has played a significant number of explicitly Jewish characters, the first one—to the best of my knowledge—being Hiram Jaffa in Move (1970), a quirky, somewhat peculiar movie that came on the heels of his early successes, Mash and Bob, Carol, Ted and Alice.

This leads us away from Jewish identity to a discussion of Move, a film I have liked since I first saw it almost 40 years ago. Again, Gould seems genuinely grateful for my interest in the film. “It was my first failure. The theme and composition of the film weren’t consistent with the product the film had to be. It was based on a book, called Move, by Joe Lieber. It was about responsibility They brought in comedy writers, but it wasn’t about comedy. It was serious, about a man who was lost, lost in his ignorance and inability to commit to the responsibility of being in a relationship. It was directed by Stuart Rosenberg who had done Murder Inc. and Cool Hand Luke. And comedy wasn’t his strongpoint. The picture didn’t work, because it couldn’t make up its mind. But one of the things that meant a lot to me with Move was that it was produced by Pandro S. Berman. And Pandro S. Berman was an iconic Hollywood producer who had produced Top Hat and Gunga Din.”

Gould begins to describe, in minute detail, the making of the film. He seems to remember not only every scene, but every shot. Evidently noticing my look of awe—I can’t remember most of the things I wrote last year—he says, “I have a really good recall. And I’m grateful for this and, I think blessed, which also goes back to our roots—not to forget, and not to deny.”

He ends his discussion of Move with an interesting anecdote: “The cinematographer was a guy named Bill Daniels, who was an ‘elder.’ He was, I was told, Greta Garbo’s favorite cinematographer. Well, when we are young, and especially if we are succeeding, we become a little arrogant and egotistical. So he said to me, ‘What about makeup? You’re not using any makeup.’ And I told him that I had discovered that once the camera is rolling, and the sound is on and the director says, ‘Action!’, the blood comes a little closer to the surface of the skin. And so I would look a little different on film than I did to the naked eye, and that he would see more color in me than he did at that moment. And he, who was more experienced than me in all kinds of ways, said when he looked at the film that I was right. Now, I’ll do what the departments want me to do, as far as being able to fit in more with people. I have to trust more. Because you cannot work in this field without trust.”

Of which of his films is Gould most proud? He replies, “Well, I believe that a grain of pride is good for the heart but no more than that. It can be blinding. I say to people—students, children and friends—that some of the pictures I’ve been in are better and some aren’t. But that I could look at any one of them and find a reason for being there.”

I wanted to ask him when he knew he was going to be an actor. I got as far as, “When did you know” before he cut in with, “I never knew.” He then recalled his early childhood pastime of doing pantomime to records, and went on to recall his early days in the chorus of Broadway productions. “I loved being in the chorus, I loved the movies and I loved listening to the radio.” When I asked if there wasn’t some moment of epiphany when he knew that acting was his destiny, he replied, “That’s bullshit!”

Pursuing a different train of thought, Gould says, “Even after working with Ingmar Bergman, I thought, ‘Well, I’ve got all the goods.’ I knew I had talent. I thought it was about being talented. What I didn’t know was that it was all about business. Business and politics. And that’s where I got into trouble. And I had to give up or let a great part of my career be taken back. But I didn’t know how to—and I was unwilling to—compromise. And I was so successful through that initial period of time that I really thought I had control. I even produced a picture then, Little Murders.”

Asked what kinds of compromise he was unable or unwilling to do, Gould begins to answer before the question was finished. His voice raises and his face becomes animated, almost angry, as he replies, “Being able to accept the ignorance, the callousness, the shallowness of the business quarter who are responsible for financing what I want to do!”

In spite of this, however, Gould maintains that he is not dissatisfied with his body of work. “I’m so glad you liked Move,” he says to me. “Because I find that my work has been appreciating from my having endured and survived and continued to do it, and from not to allowing ego or vanity to interfere with the possibility of doing something more. And I do believe wholeheartedly in modesty and humility. Ego is toxic. Ego and vanity. But not wanting to be a hypocrite, I’ve had to accept my own. I’d just like to be as selfless as possible and continue to work more.”

At this point, an earnest young woman comes over to announce that our “exactly-one-half-hour-and-not-one-nanosecond-more” is up. Gould breezily waves her away, informing her, “We’re talking here.”

As I finish silently thanking God, the interview continues with my asking Gould if he was planning to direct. “It would seem to be unlikely, but I don’t give up,” he says. “I have nothing to direct, no one has asked me, and I have nothing to prove. But I know something. I understand chemistry, and now I understand composition and orchestration. Each film is an orchestration unto itself. I would just want to work with those of us who are on the filmmaking team, knowing that no one of us can be any more than the least of us.”

Despite the frustrations and compromises of his long career in films, Gould has apparently not given up on Hollywood, or actually what Hollywood does. Gould remains enthusiastic about Hollywood’s ability to communicate. He says, “Hollywood is an industry. Hollywood is not necessarily a place. Hollywood is the industry of perpetuating and projecting imagination, projecting thoughts. These are things to share. I believe that there’s nothing of value other than what we have to share. And it’s one thing to share goodness and accomplishment, but it’s another thing to share a problem. Once people are willing to communicate, we can see that no one of us can have a problem that one of us didn’t have before.”

So what’s ahead for Elliott Gould? “I’m going to do a picture with a young French writer–director named Bartholome Grossman. And I’m going to play a character for him in a French film that’s being done in English based on a book entitled Out, about a financial world with all kinds of unsavory characters. I’m playing a kind of Bernie Madoff character.” Long term, Gould says that he is toying with the idea of doing a remake of the 1975 hit comedy The Sunshine Boys; as well as a sequel to The Long Goodbye, the 1973 film based on the novel by Raymond Chandler and directed by Robert Altman, in which Gould delivered a completely new take on the character of private detective Philip Marlowe.

My final question to Elliott Gould is what he would like to do if he weren’t an actor. I expect at least a second or two of surprise and hesitation, but Gould returns my serve faster than Venus Williams. He replies, “If I could really be educated and had the discipline, I would love to be a doctor. I would also be interested in studying and practicing law. I’m very interested in education. If there’s a future, then it’s probably in education and science. At a film festival in Port Townsend, Washington, where they were showing a few of my films, I was asked to talk with 11th and 12th graders. I went into the classroom and they had a big poster of Albert Einstein with a picture of him that I hadn’t seen. And it was with a quotation which was, ‘Where the world ceases to be the scene of our personal hopes and wishes, where we face it as free beings, admiring, asking and observing, there we enter the realm of art and science.’ I admired the poster so much, they gave it to me.”

The interview finally ends with Gould giving me his email address and urging me to write to him. He promises to send me a poster and other publicity material from the film Move. He wanders of, mumbling vaguely about possibly getting a couple of hours in a swimming pool. I sit for a few minutes after he is gone, attempting to absorb my moment with Elliot Gould, legend, icon, star, and—as it turns out—mensch.

Image credit: Elizur Reuveni

Carl – that was a great article – you showed the ‘real’ and ‘human’ side of him. I really enjoyed reading this (by the way I usually don’t like magazine articles about famous film stars but this was really interesting)

Great interview by one who is clearly a gifted interviewer. Thanks for the insightful picture of one of Hollywood’s most gifted actors.

Ah, my wonderful friend! You have written an entertaining and informative article that has allowed me to better know this great actor. I look forward to the next one.

Carl. Great interview. You really showed us who Gould is — A mensch.

Horef tov

Well done, Carl! Enjoyed the article very much. I didn’t think I’d be able to finish it before having to leave for work, but you snagged me and pulled me in! I look forward to reading more by you.

So glad you posted this!! Haaretz had an interview, but only in Hebrew. I read about half and ran out of time (I’m VERY slow in Hebrew). So it was great to read this. Apparently he’s a real mentsh and an interesting guy. I’m very glad, because I’ve always enjoyed watching him in the movies, but so many actors are really really not very interesting at all.

beautiful article, and I read every article/interview of Gould because he’s simply my favorite actor of all time but you more than all the other interviewers nailed it with this one, excellent work.!

Why didn’t you mention that he was the receipient of the award of excellence in cinema at the Haifa film festival, (or perhaps he asked you not to mention it??)

Comments are closed.