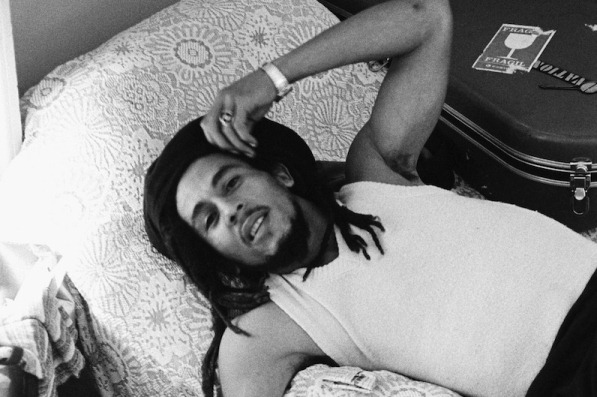

1978, the One Love peace concert in Kingston, Jamaica. After leading the country perilously close to the brink of anarchy, Eward Seaga and Micheal Manley – the patrician leaders of Jamaica’s two main political parties – shake hands on stage uncomfortably. It is stage-managed, admittedly: but after years of fraction, fighting and fratricide, no one is going to complain. And the man who brought them together on stage? Rastaman and musician Bob Marley, soft-spoken but charismatic; who had returned from self-imposed exile in England because he believed that he had a higher duty – to his people, the marginalised and disenfranchised poor of Jamaica. He was right: the people adored him, loved him, needed him to heal the country because no one else could.

But all this is almost besides the point. The question is, how did the self described “country boy from St. Ann’s” become the most popular – and quite possibly the most significant – cultural and social figure in all of Jamaica’s post colonial history?

Kevin McDonald’s new documentary Marley does a good job of joining the dots together. Much of Marley’s personal history – from his humble beginnings in rural Jamaica to his untimely death from cancer, at the age of 36 – is a matter of public record. But McDonald’s patient, unwinding retrospective fills in a lot of the gaps: interviews with some of the closest people to Marley, archival footage and recordings of Marley’s musings on his life and his responsibilities combine to create the fuller picture.

McDonald – the Oscar winning director of Touching the Void and The Last King of Scotland – is largely a conventional filmmaker. This is not meant slightingly; it’s an observation about the attention he places to the classic building blocks of documentary filmmaking, first person accounts and primary sources taking precedence over the often cloying and self-conscious interject of the filmmaker as interpreter. It certainly helps that McDonald had access to many of the prominent names in Marley’s past: Bunny Livingston, Chris Blackwell, Rita Marley and Cindy Breakspear, to name a few.

I mention these four for different reasons. Livingston, a childhood friend and latterly Marley’s step brother, particularly understood the effect of Marley’s mixed Anglo-Jamaican parentage on his self perception. He was singled out, not for being born out of wedlock or having an absent father, but for having a white absent father. Marley, we understand, grew up an outsider. Self reliance became an important part of his emotional make-up.

Marley was competitive, fiercely ambitious, with a drive that outstripped most of his contemporaries. Already reasonably popular in Jamaica, but with neither cash nor connections to show for this, Blackwell – the owner of Island Records – gave Marley and his group, the Wailers a chance to crack the big time when nothing was working their way: £4000, no questions asked, to record their breakthrough album, Catch a Fire.

But Blackwell was also an astute businessman, and had every intention on cashing in on his invaluable investment. He commissioned overdubs on the finished record, to soften the reggae vibes and to fit his marketing strategy of the Wailers as black rockers. He pushed them to tour incessantly, not for money but to engage with new audiences. Tosh and Livingston, two thirds of The Wailers, were not terribly happy with this. But Marley understood the need for give and take. He could keep his eye on the prize, and it was this difference that ultimately led to the break-up of the original Wailers line-up. Marley, the evangelist, needed to get his message to the people.

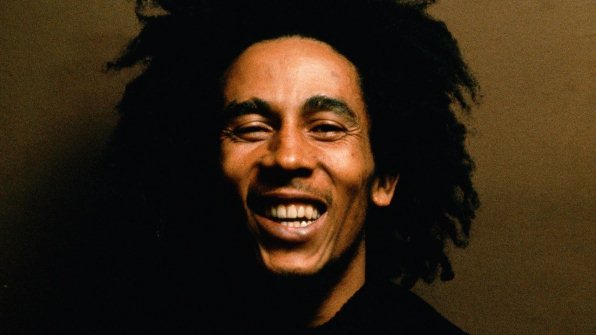

What was this message? Love, pretty much as simple as that. Marley embraced a Rastafarianism relatively young, with all that the spiritual message of then still nascent creed dictated. Love overflowed from Bob, metaphorically as well as literally – in his lifetime, he had 11 children from seven relationships. McDonald talks at length with Rita, Marley’s wife and Cindy Breakspear, his most notorious conquest: but one can’t help but wonder if McDonald might have missed a trick at this point. There is such a glaring contradiction between Marley’s humanism and his complicated relationship with women, and the film never quite resolves this satisfactorily. One doesn’t doubt that Marley never set out to hurt anyone: but with Rita and with others, the scars show.

Love and harmony and all that Kumbaya aside, being a music megastar in the 1970s was a tad complicated if one was (1) Black and (2) tended to speak in Jamaican patois. Marley – as archival footage shows – was articulate, good humored and quick witted: when an interviewer asks him if he is worth millions of dollars, Marley merely smiles. “Me no measure my riches in dollars,” he replies, “My richness comes from life.”

Anyhow, some people tended to rub up the wrong way against him. Take the British tabloid press, not particularly known for its sensitivity and racial awareness. “Beauty and the Beast,” declared one paper about his relationship with the (in the general sense) better known Miss Breakspear, 1976 Miss World. The ganja smoking and dreadlocks masked the opportunity to engage with Marley’s simple message of universal brotherhood.

Ironically, Marley always fretted about not making the headway with black American audiences that he did with their Caucasian counterparts. And, although McDonald is too nuanced a filmmaker to telegraph this overtly, one can’t but wonder whether this might have in some form contributed to his death. Marley toured incessantly across the States, striving mightily to break new audiences. He was on a mission from God, he genuinely believed. And, like most prophets, personal neglect follows from answering to a higher authority. Melanoma had been diagnosed in Marley’s big toe in 1976. It was treated, but checkups were never followed through. And by the time its re-emergence made itself clear, during a tour of the United States in 1980, it has spread to his brain, lungs…there was nothing more to be done.

Marley is a sympathetic portrait; it is also a comprehensive one. There are few people who would survive the through scrutiny of their whole lives without losing some of their credibility. That Bob Marley – Rasta, singer, visionary – emerges from this film with his reputation intact says much about him and his documentarian.

Marley is screened as part of the Docaviv International Documentary Film Festival 2012, the next screening will take place on Wednesday, May 9th. From May 10th, Marley will have special screenings at Orlando Cinema, ZOA House Tel Aviv.

Marley (2012, US/UK) Directed by Kevin McDonald. 144 mins, Eng (Heb subtitles)