Remembering, a new exhibition at the Israel Museum brings together, for the first time, works by two cultural icons of the 20th century: German multi-media artist Joseph Beuys(1921-1986); and Polish artist and revolutionary theater director Tadeusz Kantor(1915 -1990). The initiative for this juxtaposition came from Jaromir Jedliński:, a guest curator from Warsaw, who organized this show in collaboration with Suzanne Landau, the Museum’s chief curator of Fine Arts (shortly leaving to take over as Tel Aviv Museum’s new director)

60 works are on display, many loaned from major public collections. They range from installations and found objects to painting and drawings. Also well represented are photos and films documenting performance or theater pieces. In the case of Beuys, this visual documentation is very well known.

The life experiences of Beuys and Kantor were quite different, Beuys served in the German Luftwaffe during World War 11; Kantor lived through two World Wars, the annihilation of Polish-Jewish life, and later, the repressive influence of Communism. He grew up, he once said, in a Polish town “in the shadow of both a church and synagogue.”Nevertheless this presentation clearly illustrates that there are many parallels. Both men extended the boundaries of art through an emphasis on performances, happenings or theater pieces. Also, the themes that they dealt with were similar: war and its aftermath, Polish-German- Jewish relationships, myths and classical mythology. Memory, personal and collective, its retention, repression and distortion of the truth fuelled the artistic activities of both artists, as did their strong social consciences.

While Kantor’s prime concern was bridging the gap between the theater and real life, Beuys saw his central task as a pedagogue or shaman. “To be a teacher,” he famously said “is my greatest work of art.” Behind his work there was always a theory, philosophy or social aim. One example is the filmed performance How to explain Pictures to a Dead Hair (1965). Here, Beuys, his head coated in honey and gold leaf, is seen cradling the body of dead animal, eventually moving round a room with pictures hanging on the wall – a scene that is an ironical comment on attempts to explain or teach art. It has also been suggested that this happening was a metaphor for art as a healing process in a world seeking new hope for the future.

Beuys introduced the term Social Sculpture to illustrate the ability of an artwork to shape or represent society. A striking example of this genre is his installation End of the 20th century. (1983-85). It consists of 44 basalts blocks laid out in a large gallery space. Some pieces are laid on top of each other. A small cone – a sort of wound – has been drilled out of their top surfaces, and later plugged with clay and felt. As a historical commentary this work appears to allude to the terrible devastation, moral as well as physical that took place in Europe during the last century.

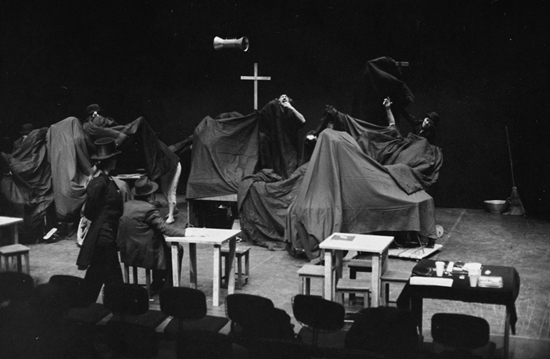

The exhibits are arranged so that this installation by Beuys converges on an equally pessimistic work by Kantor. It is Assemblage for the End of the Twentieth Century (1988), a photo still from his 1988 theater production I Will Never Return Again. One sees a darkened stage, an illuminated cross, and figures covered by a black shroud with only their arms projecting – a scene suggestive of hopelessness and suffering. The actors in this production were members of the experimental CRICOT 2 Theater that Kantor founded in Krakow in 1956 and became world famous.

Both Kantor and Beuys were fascinated by death, some of their darker memories surfacing in the form of archeological art where ‘artistic’ relics signify the remains of human existence.

The Dead Class (1975) one of Kantor’s best known theater pieces is represented here by rows of mannequins seated on worn, dusty schoolroom benches. This installation was only part of this production in which Kantor played the role of teacher presiding over a group of elderly people whom he confronts with ‘dead’ figures representing their younger selves.

Beuys’ installation Palazzo Regale (1985) also speaks of death. It may be likened to a royal mausoleum. We enter a room with brass panels covered in gold dust on the walls. It houses two glass cases containing objects associated with Beuys personal biography; in particular, references to the much repeated story of his rescue by Tartars when his plane was shot down in 1943 on the Crimean front. Tribesman apparently saved his life by wrapping him in fat and felt, materials which he would use repeatedly in his work.

Displayed in one of the glass cases are items immediately identified as his such as a rucksack and a walking-stick. The other vitrine contains the iron head of a man, recycled from an earlier performance, and a fur coat where the body should be. A pair of cymbals (also used in a previous happening) and a conch shell, an insignia of royalty in many cultures, completes this miscellany of objects. The throat of the blackened head is marked with an X, as if to indicate that this body lost the power of speech. This piece, Beuys last major work, was installed in 1985 at the Museo di Capodimonte in Naples. It seems to have presages his death. Beuys died in Düsseldorf the following the year.

A distinguished exhibition that opens up new perspectives on two great artists of the 20th century.

The exhibition will be open through October 27th 2012

Israel Museum, Jerusalem

Amazing! Mind Boggling!Provokes a lot of thinking

I wish I knew more about The 2 artist prior to visiting the exhibition.

Will try to visit again

Cant wait!!

Comments are closed.