I was in the middle of a rehearsal in a dance studio when I felt my phone vibrate. The dancers were taking a break, so I put my guitar aside and picked up the phone. It was a producer I knew, calling from London. He told me about a new project of Time Warner’s: they were starting a new TV channel in Great Britain. They were looking for a composer. He said that if I wanted to be considered for the position he would email me instructions for preparing the five music samples which should be completed and sent by the following morning.

Two hours later I was already in the recording studio, reading the instructions and beginning to compose. I worked late into the night and when I finished I emailed the new music files to the producer. I got the job.

This was the way we worked for the next few months: each day the London production people wrote, shot and edited original videos that would serve as the marketing package of the channel and the talk shows. At the end of the day the videos were converted to files that could be sent via email. I received them within minutes and began composing music for each video according to the accompanying instructions. Sometimes I received 5, 7 or even 10 videos in one day. After a long night’s work I sent the new music to the producer who then gave me his feedback. I, in turn, sent him my corrections.

We worked like that for six months. The people I worked with every day had never met me face to face. Although we had developed a connection over time and even a sort of friendship – they did not know me and I did not really know them. Between our two continents there was daily communication that was fast, creative and very intense. A few weeks later as I sat on a plane to London to participate in the launch of the new channel, I thought about the people I was about to meet and the creative process we had shared. I thought about the technology that had enabled us to create something together in this unique way.

Technology and creativity had merged into a compound and were inseparable. Two aspects of the work depended on technology; the most important was communication. Our ability to be in constant, continuous and immediate contact – sending material in real time from England to Israel and back, turned the term “global village” into an amazing reality that shrunk the world to the size of a computer keyboard. At no stage of the process did I feel that there was any difference between working with a production company in London and working with one in Tel Aviv.

The other element was my method of working and composing the music.

In the not-too-distant past, a composer had to imagine the arrangements of his works and write them down without having heard them until the composition is complete; musicians receive the score and perform the piece. At this stage a new problem arises because each musician plays in his own style and to a certain extent alters the role that the composer envisioned for that particular instrument. The situation is more extreme in classical music due to the large number of musicians with vastly differing abilities and the inability to ask the composer what his intentions were for a particular piece. The conductor and musicians then become the interpreters of the composition in a process that is lengthy and dependent on many variables.

Today many musicians have their own professional computer-based studio. This enables the musician to play and record many instruments while still in the process of composing, using recording and editing software and samples of a variety of instruments, such as: wind instruments, string instruments, and drums. In a way, the contemporary composer has joined his colleagues the painters and sculptors. A painter has all his paints and brushes at hand and is able to choose among them as he works. The painting changes throughout the process until the artist decides that it is complete. He can go over lines he has already drawn, change their color and form. So can the contemporary composer.

When I compose I can record an infinite number of tracks, edit, and change or delete any one of them at any time. I record drums and percussion, then record bass and guitars “over them”, add the colors of horns, viola or piano. Then I go back over the material and examine the previous roles I assigned the different instruments in light of the newly recorded material. This potential to create does not even take into account electronics and electrical instruments that add an infinite range of sounds and rhythms.

Sometimes I can have 50 or 60 tracks in one composition. To put this number in context, consider that until 1968 all records (yes, even The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper) were recorded on a 4 track tape!! The computer frees the mind from technological constraints and determines a new way of working. Contemporary methods enable me to compose without fear. Any idea, extreme or strange as it may be, is played, recorded and assessed in real time, the results can be played within minutes.

While not all composers play a variety of instruments and must therefore hire musicians to perform their works, even under this constraint the speed and relative ease of recording affects the process of composing and arranging. It is important to emphasize that the computer does not write the composition, just as a good guitar does not compose for the guitarist. The computer, although complex, is merely a tool, and does not eliminate the need for creative and performing talents.

The amazing possibilities that opened up for me with the advent of computers in my daily work as a musician forever altered my horizon of expectations and my dreams. My ability as a musician to compose, arrange, play, record, edit, mix, master and burn has transformed me. I am not dependent on large, expensive studios, musicians, and producers. I can quickly and easily create music for a wide variety of purposes in a world job market that is wide open.

One occasionally hears the criticism that the ease of production has led to a saturation of the market with mediocre music. In the past, without record companies that selected artists and financed expensive studios and technicians for a select few, there was no way for an independent composer to publicize his work. Talented artists were not always able to find a way to reach the public. Today an amazing variety of music of all genres, styles and quality finds its way to the broadcast channels and the internet, for free.

Technology is constantly moving forward, it exerts a force of its own. It is a part of our world that does not need to wait for our approval to confirm its presence or necessity. It is developing at a fantastic rate, often much faster than we can comprehend, and whoever does not recognize the power it conveys, consigns himself to remain outside the fence that surrounds a giant, perhaps infinite, playground.

In conclusion I would like to quote Brian Eno, one of the most important and respected musicians in contemporary music history. Over the past four decades, Eno composed, produced and collaborated with some of the greatest musicians in the world. He played a role in the creation of dozens of albums with musicians such as: David Bowie, U2, Coldplay and David Byrne. The quote is from an essay Eno wrote in 1979 when magnetic tape was a technological breakthrough and computerized studios existed only in the realm of science fiction: “I think there is a difference in kind between the kind of composition I do and the kind a classical composer does. This is evidenced by the fact that I can neither read nor write music, and I can’t play any instruments really well, either. You can’t imagine a situation prior to this where anyone like me could have been a composer. It couldn’t have happened. How could I do it without tape and without technology?”

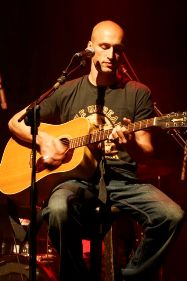

Didi Erez is a singer, songwriter, musician and contributing editor of Midnight East. He has composed music for dance, theater, movies, animation and TV. His CD “Kol Mabat” appeared in 2007, receiving excellent reviews and nominated for “song of the year” and “discovery of the year”.