‘Coming Home’ should be the title of Naftali Bezem’s major retrospective. Not just because this artist, now 86 years old, returned to this country in 2009 after 15 years self -imposed exile in Europe, but because he has come home in a deeper sense. After years of frustration and disappointment, the art establishment now seems ready to offer Bezem a solid place in the history of Israeli art. What was the situation before? From the 1940s onwards, Israel’s mainstream artists adopted international- abstract art to the exclusion of all other trends. Figurative painting like Bezem’s was considered obsolete. In addition, they scorned Bezem’s unswerving intent to produce art with a Jewish, historical or social agenda. This exhibition – the opening attended by more than 900 people – proves that the judgment of the art establishment was seriously flawed.

Out of scores of paintings and drawings that Bezem has produced in the last 60 years, either in Israel or Europe, curator Ruthi Ofek has made a clever, tight selection that showcases the best of Bezem. Included are several iconic pieces that have not been exhibited in public for years. The works are grouped around three major themes: social criticism of life in Israel, the family of the artist, individual and collective memories of the Holocaust, and Bezem’s key motif – The Boat.

Bezem’s life story is integral to understanding his art. He was born in Essen, Germany, into an orthodox family who had emigrated from Poland. But in 1938, his family were expelled from the country and forced into a refugee camp. At the age of 14, just days before the outbreak of World War II, his parents succeeded in sending him to Palestine under the auspices of Aliyat Han’oar (Youth Immigration). For years, Bezem lived in constant fear for the safety of his parents, eventually learning that they had perished in Auschwitz. He was left alone with his memories.

In the mid 1940s, he studied at the Bezalel School of Arts and Crafts in Jerusalem where one of his teachers was the extraordinary Jewish symbolist painter Mordechai Ardon. Imbued with the ideals of HaShomer HaTzair, a Socialist-Zionist youth movement, Bezem saw his future as an artist with a social agenda. Believing that mural painting was the best way forward, he left for Paris to study in a Catholic school that specialized in teaching wall painting techniques. In1951 he returned to Israel with his wife Hannah and infant son Yitzhak, and became an illustrator and art teacher for the Kibbutz movement.

Presented under the title We Have Come to Build – and to be Built in Return (a phrase taken from a pioneer song) are examples of Bezem’s work from the 1950s in a social realist style. These include charcoal drawings and paintings documenting life in the transit camps set up after the war. Eye-catching, in particular, are a bird’s eye view, in jewel-like colors, of the geometric layout of a camp; and a touching portrait titled The Madonna of the Ma’abara showing a young woman, eyes lowered, feeding her baby in the shelter of a tin shack.

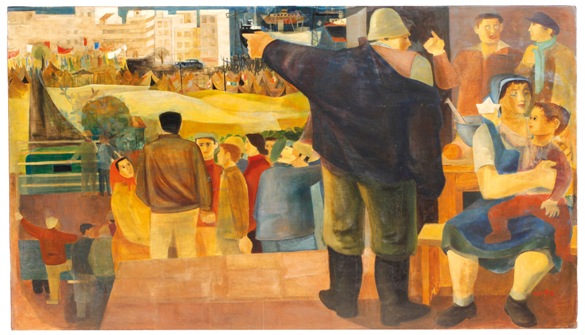

To the Aid of the Seamen (1952) Bezem’s best known social realist painting created a public uproar when it was first exhibited. The artist was berated for daring to criticize a government decision to end a seamen’s strike through the use of force. In this picture, which derived inspiration from Italian and Mexican mural painting, strongly modeled figures are set against flat areas of color. Depicted is the moment when laborers and kibbutzniks are leaving to join the strikers, who are seen in the distances, flags flying, marching beyond a cluster of tents.

Amongst paintings that take the Bezem family as their theme, there are many realistic examples: portraits of his parents (as he remembered them), a study of his wife reading and sketches of his two sons. In general, Bezem treats the Holocaust largely through symbols, but some paintings, like Mass Grave showing a religious Jew digging his own tomb, are shockingly realistic. But progressing through the exhibition one notes that from 1960 onwards Bezem abandoned realism and overt social criticism. Instead, he opted to paint mysterious scenes in which the objects are amorphous, suggesting rather than defining their identity. Or else, he created well-planned surreal compositions in which his personal lexicon of symbols relating to Jewish and personal history, emigration and settlement, are clearly stated and intertwined.

The Table (1960) is a fine example of one of his dream-like paintings. It is part of a group, the latest completed only a few months ago, that relates to Bezem’s memories of the last Shabbat spent in his parents’ home. In this particular work it looks as if a softly colored veil has been drawn across the scene, blurring many details. Clearly shown is a woman (Bezem’s mother), dressed in blue, standing beside a table filled with an assortments of objects which are not identifiable, save for a pair of a candlesticks, and the body of a rooster – a sacrificial symbol. To the left Bezem has painted in an upright ladder, his personal symbol for Aliyah; while on the right is a cactus plant, symbol of new beginnings in the Land of Israel. High up, perhaps heralding a brighter future, a hand stretches out to touch a deep-red sun.

.

Lion Gate, conceived mainly in a palette of grays, deep blues and purples, is a striking example of those paintings in which Bezem presents his signature motifs with clarity, even though the overall meaning is often beyond one’s grasp. In the upper far corner, small white figures are grouped at the entrance to what appears to be a gas chamber. Below, is the nude body of a woman, representing the Universal Mother. In her hands she clutches candlesticks in the shape of plowshares, one is unlit in memory of Bezem’s son Yitzhak who died in 1975 in a terrorist attack. To complete this composition, in which past and future are welded together, a warrior like figure clings to a circular ladder, and another set of candles sprout from the head of the Lion of Judah – Bezem’s symbol for a survivor.

Just visible at the top of the Lion Gate painting is a tiny boat. Its ‘captain’, the artist, wearing a fedora hat – Bezem’s symbol for a European immigrant. This is the same boat in miniature that appears in one form or another in so many of the paintings on exhibit to represent flight or a journey on the way to settlement in the Land of Israel. But in addition for this show, Bezem has constructed a whimsical three-dimensional version of his boat from painted wood. In it, he has placed his own likeness: a face with a curly beard made from twists of copper, and a figure whose body ends in the tail of a fish. Black and white stripes recalling phylacteries cover his wing-like arms. Present too are other familiar symbols: the ladder, plants, and, of course, the ubiquitous candlesticks. Paddles and oars jut out from this boat, striking the ground. Bezem has arrived home.

A warmly recommended exhibition.

Till April 2, 2013. Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 27 Shaul Hamelech Blvd, Tel Aviv.

This fascinating article is very well written and will be of great help when viewing the exhibition: it provides an understanding not only of the expressions of the artist, but also of the artist himself.

Comments are closed.