The timing of the Israeli theatrical release of Spielberg’s Lincoln could not have been more auspicious: January 24, 2013 – just two days after the elections. Time enough to recover from the inevitable after-effects of euphoria/despair or baffling combination of both, and seek solace and enlightenment where they can best be found: in the dark, gazing at the larger than life figure of Abraham Lincoln.

The timing of the Israeli theatrical release of Spielberg’s Lincoln could not have been more auspicious: January 24, 2013 – just two days after the elections. Time enough to recover from the inevitable after-effects of euphoria/despair or baffling combination of both, and seek solace and enlightenment where they can best be found: in the dark, gazing at the larger than life figure of Abraham Lincoln.

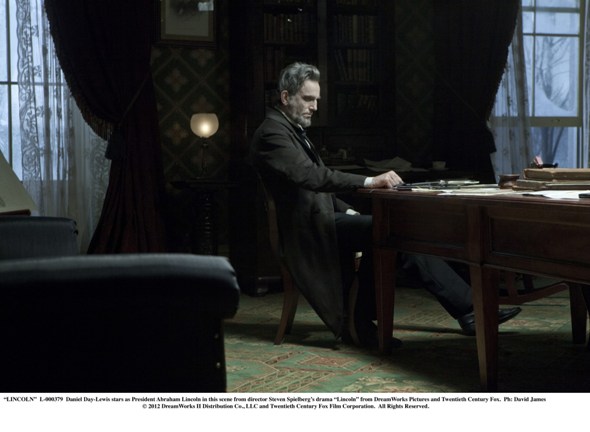

Set in the last four months of Lincoln’s life in 1865, the film focuses on the political arena as President Lincoln pushes for the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery. Observing the legendary Lincoln, with the Civil War as a backdrop, and a pantheon of Hollywood stars, one might easily imagine Lincoln becoming a historical extravaganza, with lavish period sets and battle scenes taking precedence. Happily, this is not the case. Instead, one is treated to a very intimate look at the people who were at the front lines, in the front parlors, and the smoky backrooms of a critical moment in history.

Daniel Day-Lewis presents an articulate, Shakespeare-quoting president, with equal measures of political acumen and folksy charm. One sees a weary President, who has led the country through years of war tearing the country asunder; one sees the man, the husband and father, who struggles with some of the same decisions facing any parent. When son Robert abruptly leaves his university studies at Harvard to enlist and fulfill his civic duty, Lincoln’s dilemma, knowing that the wrong decision either way might cost him his son – whether through war or emotional estrangement, and the ensuing argument between Lincoln and his wife Mary Todd Lincoln (Sally Field), might be the dilemma of any father.

Yet it is Lincoln the politician, as he contends with associates and adversaries, who provides the thrills and suspense. The mounting pressure to end the war, weighed against the concern that once the war is over and the Southern states rejoin the Union, the issue of slavery may be all too easily cast aside, strengthen Lincoln’s resolve to pass the Thirteenth Amendment without any further delay. There is immense pleasure in Day-Lewis’ portrayal of Lincoln as a strategic thinker capable of bold moves and quirky alliances (James Spader as the blithely immoral “we need money for bribes” Bilbo is a delight). Watching the film, the pleasure was pure and unsullied for this writer, as it was easy to concur with Lincoln and his cohorts that slavery must be outlawed, and by any means possible.

Reflecting on the film in this election week, this intimate view of the political machine, whose human face has been little altered by the passage of time – political strategy and alliances in 2013 are much like those of 1865 – heightens one’s awareness of the dangers inherent in political power, as it might be played in the hands of a leader of vision and morals, such as Lincoln, or in the hands of those less knowing, and less responsible. What if a man of Lincoln’s stature, with his wit and skills, had set his mind on other goals? Would I still be sitting in the dark, applauding his subterfuge and verbal dexterity with as much glee, easily conceding that the ends justify the means?

Lincoln has been nominated for twelve Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Actor for Daniel Day-Lewis. Daniel Day-Lewis was awarded the Golden Globe for Best Actor in a Motion Picture Drama for his performance in Lincoln. Lincoln will be showing in Israeli theatres as of January 24, 2013.

Lincoln has been nominated for twelve Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Actor for Daniel Day-Lewis. Daniel Day-Lewis was awarded the Golden Globe for Best Actor in a Motion Picture Drama for his performance in Lincoln. Lincoln will be showing in Israeli theatres as of January 24, 2013.

Lincoln (US, 150 min, English with Hebrew subtitles)

Director: Steven Spielberg; Screenplay: Tony Kushner, based on Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Team of Rivals; Producers: Steven Spielberg, Kathleen Kennedy; Music: John Williams, Cinematography: Janusz Kamiński; Editing: Michael Kahn; Starring: Daniel Day-Lewis, Sally Field, David Strathairn, Joseph Gordon-Levitt, James Spader, Hal Holbrook, Tommy Lee Jones.