Justin, Roei, Elfar and Houcine don’t have very much in common, at least at first blush. The first is a quiet American, the second an acne scarred youth, all gangly arms and legs, from Jaffa. Elfar, with rounded features that shave three or even four years from his age, is Russian; Houcine, a few years older, is from the Banlieues skirting Paris, with the swagger and assumed street smarts familiar to anyone who has passed oneself off as a little older and a little more mature than the truth.

They’re all kids though, and it’s this along with the fact that they’re on the verge of commencing military service that pulls their disparate stories together in the brief, somewhat oblique documentary Enlistment Days, directed by Israeli Ido Haar. Strange as it may sound, we are in a period of almost unprecedented calm at the moment. The key is relativity, of course: Iraq was not Vietnam, Afghanistan hardly the battlegrounds of western Europe (and I do say this with full knowledge of casualties incurred by all sides). But there are campaigns still to be prosecuted, soldiers still needed to place their lives on the line. The question is how to bring people round to the notion that army service and imminent risk to the person are not necessarily two sides of the same coin.

Haar’s film – the director’s eye recording without interjection or commentary – follows its four principals in the days before they sign up for service. Roei and Alfer are commencing the compulsory conscription attendant upon all (ok, upon most, but this is a matter beyond the scope of both this film and this review) 18 year olds in their home countries; Justin and Houcine are signing up for their respective professional armies, albeit for very different reasons.

The narratives which inform the choice or justify the necessity are very different in some respects. Alfer and his father have a masculine heart to heart. The father can buy (illegally, at considerable expense) an exemption for his son. But he needs to hear the son ask for it. Duty is a word that the father uses a lot. Given the notoriously challenging conditions faced by Russian conscripts, I suppose this social imperative has to be hammered down firmly, early and often. Still, Alfer is a kid and it’s a little unsettling to think about the weight of responsibility that has been placed upon his shoulders. A touching conversation with his girlfriend only serves to remind quite how unprepared he will be for the weight – literal and metaphorical – that comes with a gun’s cold steel.

For Roie it is duty too, but it is also a Mitzvah, one that even brings Simcha. Domestic viewers are probably be familiar with the Israeli conscription process. Even so, I was a bit surprised when a serving officer, not much older than Roei himself, visits the home to inform on the opportunities that he might be able to avail himself of, once in uniform. A video is played: another callow youth (yeah, I am being unkind but seriously, these guys are babies) rhapsodises about how at his age he is already responsible for a tank and its crew. But Israelis never do the stiff upper lip terribly well; at Roei’s good bye party, it is hard to stop the tears forced through by uncertainty and, I suppose, fear.

The French experience seems rather slapdash, less committed, in comparison. Houcine is on his third attempt to sign up; the first two times he backed out at the last minute. “I’m tired of getting in trouble,” he muses. “I’m 23, I need a place of my own.” But then: “I didn’t even learn the national anthem.” One can’t but wonder at the commitment he has to a cause that perhaps he can hardly identify as his own. Not to say that the reception from the receiving officers seems much more involved. They recite, almost by rote, the opportunities that the army will offer its newest recruits. See the country, visit foreign places. One imagines that there might very well be other stuff involved, like the (as The Onion once put it) core objectives of, you know, killing other people. Houcine smiles wryly when his signing up officer tells him that he will be available, day or night, if Houcine suffers from a crisis of confidence. Even if he is in bed with his wife. “I heard you say that to the last guy,” Houcine retorts. They both laugh, hollowly.

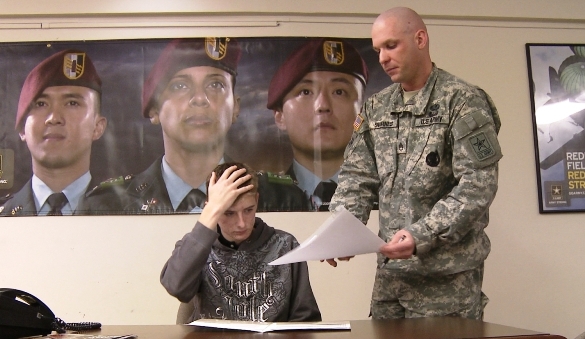

But I think the heart of the matter comes through Justin. He is guarded, says little about himself. He reads a thick paperback about military history, speaks shortly with his parents by mobile telephone. But it is what happens around him that counts for much more. When recruitment officers cold call prospective recruits, college seniors, they try very hard to sell the specious benefits of joining the professional army of the United States. “Have you thought about how you are going to pay for college yet?” Well, not specious in all circumstances.

Later, Justin and his fellow recruits swap information about their expected financial compensation. The salary for a recruit has just been increased from $1300 to $1600, which seems very nice. That’s good, but salaries are revised upwards every year, the recruiting sergeant chips in. Later, another recruiting officer cites himself as an example of the good the army can do. An African-American, he grew up in Mississippi, on the wrong side of the tracks. He signed up, 30 years past, because the army offered the best chance to make something of himself. And it did. You can tell.

And that, more than anything else, holds firm throughout the film. It is no accident that the majority of the young soldiers we see are drawn from the lower reaches of the socio-economic pool. When opportunities for social progression are so limited, is it right or fair to pretend that choice actually underpins the decision to join up? I don’t really think so. For better or for worse, the conscripts at least have an underlying ideology that they can try to embrace. Elsewhere, less so. But either way, the concept of a democratic and egalitarian army is weakened by the end of the film. Which, perhaps, we didn’t need Enlistment Days to tell us. But it does the job, and does it competently.

Enlistment Days is currently showing in Israeli theatres, follow updates on the facebook page here.

Enlistment Days (Israel, 2012, 54 min, English, French, Hebrew & Russian with English subtitles)

Directed by Ido Haar