Prepare for shocks and surprises if you visit “Honey I’ve Rearranged the Collection” – a selection of works from the Phillippe Cohen collection of contemporary art, curated by Ami Barak. A believer in the questionable statement that ‘Painting is Dead,’ Cohen is an ardent collector of conceptual – ideas – art. In fact one of his star possessions is an artwork that does not exist in material form. By the British-born artist Tino Sehgal it comprises a performance from 2002,’ bought’ from the artist in which a man walks up and down a room repeating “This is Technology” in the clipped diction of an electronic voice. (The sale of this ‘work’ consisted of the artist speaking to the purchaser in front of a notary and witnesses.)

Don’t, however, dismiss Sehgal’s work too quickly, for it is for pieces like this – employing voice, language and movement as raw materials -that Sehgal was recently awarded the 2013 Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale, the art world equivalent of the Nobel Prize.

Cohen has mostly amassed contemporary French, North American and Israeli art. Just about half of his collection is on view here – some 100 works in a variety of media. The focus is primarily on the interaction between texts, language and imagery, with photos and video pieces – the moving image – prominently represented.

Introducing the show is The Cabinet of Unforgettable Components, a wall hung with small objects that are evidence of the warm links between the artists and the collector. Items range from two exquisite paintings of fireflies by Philippe Parreno (2012) which are titled Drawings for a Friend, to a stark photo of a tooth by David Shrigley (1997), a Scottish artist known for his quirky humor. This image, with Vote Tooth printed on it, references Cohen’s ‘other’ profession as a dentist.

Inside the galleries, the works are grouped under fanciful titles, which like the overall title of this exhibition Honey I Rearranged the Collection are quotes from the titles of individual works that are on exhibit here.

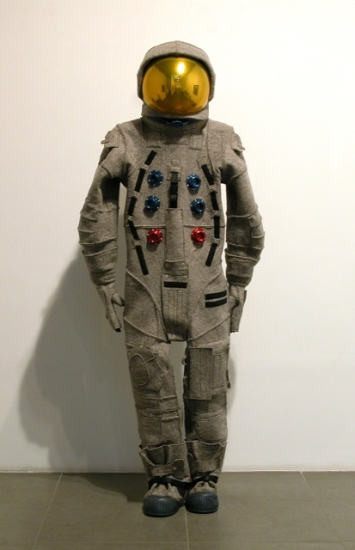

Installation (10 costumes) and video. The visitors had to get dressed with the Pinocchio suit before entering the screening room and watch the video.

43’50”

Edition 3/4

Courtesy the artist and Galerie Air de Paris, Paris

While there is some overlapping of themes, the groupings are quite meaningful. For example, Nothing is True, Everything is Permitted brings together works with humorous overtones but having a subversive content. This is best illustrated in Paul McCarthy‘s Pinocchio installation where visitors were asked (not in Israel) to approach a rail of clothes and put on yellow overalls, red plastic shoes and a mask with a long tube for a nose. They then enter another room to watch a video in which Pinocchio – McCarthy himself – is covering himself with chocolate and tomato paste and indulging in peculiar antics. This all starts out as fun, but as the film progresses, the audience (myself included) began to realize that this was no harmless fairy tale, but a scene suggesting perversion and chaos.

There may also be deeper connotations to Miri Segal‘s installation Whatever you Say which comprises a video showing two parrots tripping back and forth on their perch. Visitors to this gallery can speak to the birds through a microphone, and they respond (without comprehending a word, of course.) Segal, in fact, may be commenting on the behavior of humans not birds, making reference to a tendency for people to copy the actions or words of their friends or their leaders without any real understanding what they are doing.

Wool, felt, aluminium, steel, plastic,

183 x 66 x 61 cm

Edition 2/3 (+1 AP)

Photo Adam Reich

In the section I’m making Art, a characteristic of contemporary art is highlighted,: the borrowing or reinventing of images derived from the work of other artists. One interesting example is Matthew Day Jackson‘s Apollo Suit made from felt, a material associated with the late and very famous German artist Joseph Beuys. During War II, as a gunner in the Luftwaffe plane, Beuys was shot down on the Crimean Front, claiming later that he was rescued by Tartar tribesman who wrapped his body in animal fat and felt and nursed him back health. With his choice of felt for this mythical astronaut’s suit Day Jackson appears to concord with Beuys’s belief that this material has magical properties that would, in this case, ensure the space traveler’s safe return to earth.

Another fascinating appropriation (exhibited in another section) concerns two early 20th century (?) portraits of a bourgeois couple owned by Hans-Peter Feldman, an artist who specializes in the collecting, ordering and re-presenting objects. Sticking blobs of red paint on the noses of the man and his wife, Feldman turns these staid people into clowns, and, at the same time, he is clearly mocking the venerable traditions of portrait painting.

With Alice Laitner, Youngblood’s girlfriend and alibi witness at trial

Served 8 years of a 10.5-year sentence for Sexual Assault, Kidnapping and Child Molestation, 2002, Chromogenic print, 121, 92 x 157, 48 cm,

Edition 5/5, Courtesy the artist and Almine Rech Gallery, Paris-Brussels

Many of the photos, videos and independent objects exhibited under the title No More Reality highlight the flaws of contemporary society, especially the rule of law. The most striking exhibit, Larry Youngblood, comes from The Innocents, a photo series by Taryn Simon featuring the lives of people who served time in prison for violent crimes they did not commit. Wrongful conviction can often be a case of mistaken identity. If this is the case then photos may play a major role. Simon’s documentations illuminates the failure of this medium to reflect the truth, and its terrible consequences.

This exhibition abounds with thoughtful, clever and original works. So, if we are to believe like Philippe Cohen that “Painting is Dead,” here is proof that there is a wealth of talent out there already replacing it.

Petach Tikva Museum of Art, Yad Lebanim complex, 30 Arlozorov St., Petach Tikva. Tel: 03- 9286300.