Imprinting on Clay, the Seventh Biennale for Israeli Ceramics, is billed as a contemporary overview, this year’s subject expressing links between culture and memory. But since representatives from different generations are amongst the 66 participants, this show may also be viewed as encompassing the whole local history of this medium – and this is what makes this presentation so interesting, besides the presence of many high quality works illustrating a variety of approaches to the central theme.

This display of more than 200 works has been skillfully assembled by curator Anat Gatenio. No easy job. Historically, a starting place might be a model for a monumental work by Gdula Ogen, head of the Ceramics Studies Department at Bezalel between 1962-1980, and a pioneer in the field. Now, as then, her designs draw inspiration from nature, local history and archeological findings. In this instance she shows Taboon, a structure that derives its shape from dolmans, the Bronze Age burial structures that are part of the landscape of Northern Israel. Ogen’s intention here may well have been to create a modern-day makom, a holy place in Nature for meditation.

Traditional pottery shapes are the lift-off point for many excellent pieces. Among them Shlomit Bauman‘s distinctive vessel resembling the broken shell of a giant egg. This object, the result of firing red clay and porcelain together, signifies a merger between a material representing the early days of local ceramics and a ‘fine’ one, associated with quality European wares. In a comparable vein is Shulamit Teiblum-Millar‘s sturdy water jug with its worn and mottled appearance. Her results are achieved by the use of a wheel thrown technique characteristic of this region but employing materials – porcelain, volcanic and crystalline glazes – that have their origin in Western ceramics.

A number of appealing works pay homage to European culture, or else, symbolize memories of a place, a country or a family. Several artists create icons, of one sort or another. In Canned, for example, a distinctive piece by Cohavit Ben Ezra Goldenberg, fragments of a carpet preserved in schematic bottles represents memories of Jewish life in Iran and Turkey, as passed on by her family. Talia Tokatly displays a unique ‘heirloom’, a revolving piano stool fashioned from clay, suspending it upside down from the ceiling. This, strange ‘chandelier’ is apparently, an item of furniture that Tokatly identifies with the home of her Jewish-Viennese grandparents, although she never knew them. Her exhibit is accompanied by a sound piece that relays the voices of family members recounting their personal memories.

A significant group of artists take us into the 21st century, some of them producing works termed by the curator as “markers of material and technological change.” Here one finds Lisbeth Biger‘s intriguing Time is Slipping that deals with collective visual memories. Made from clay and glass, it comprises a collection of items that are almost obsolete today such as a spool of film, letter-writing paper and a transistor radio. The impression given is that these items have become frozen in time and are now museum pieces. Into the same category is Chevi Ben-Barak‘s homage to her father who worked as a typesetter on Al Hamishmar, a newspaper that closed in the mid 1990s. Striking in its simplicity, her offering consists of outsize letters of the Hebrew alphabet conceived as stylized ceramic forms.

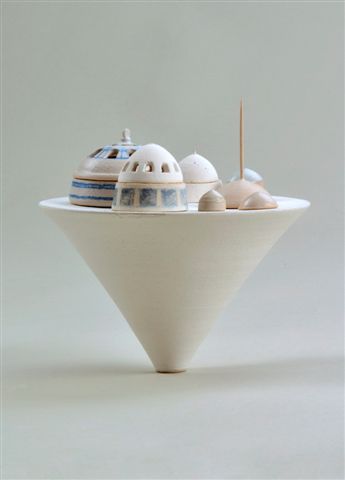

Exhibits linking ceramics with architecture are all worth a close study. They include Michella Lena Rochwerger‘s pristine ‘landscapes’ in which miniature domes, roofs and spires rest on bowls or on objects resembling spinning tops. For this outstanding work, it seems as if Rochwerger, (who graduated last year from Bezalel) has envisaged a bird’s eye view of the buildings of Jerusalem, compacting their memorable features.

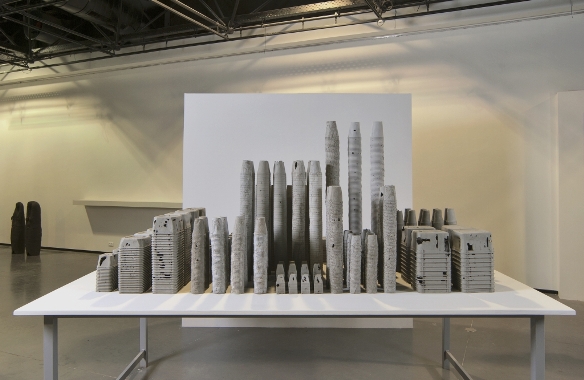

Another ‘architectural’ piece, this time in a critical vein, closes this review of a large and successful exhibition. It is Haimi Fenichel‘s intriguing ‘take’ on an urban skyline dominated by high-rise buildings. From the distance, this all-grey cluster of buildings appears to be made from solid concrete. But coming in close one finds its components are in fact torn paper cups and disposable boxes, all made from cement, but nevertheless, appearing vulnerable to destruction. Like other works on display here, Fenichel’s installation expresses the transient nature of almost everything we create.

Closes Nov. 10th 2013.

Eretz Israel Museum, 2 Haim Levanon St., Ramat Aviv