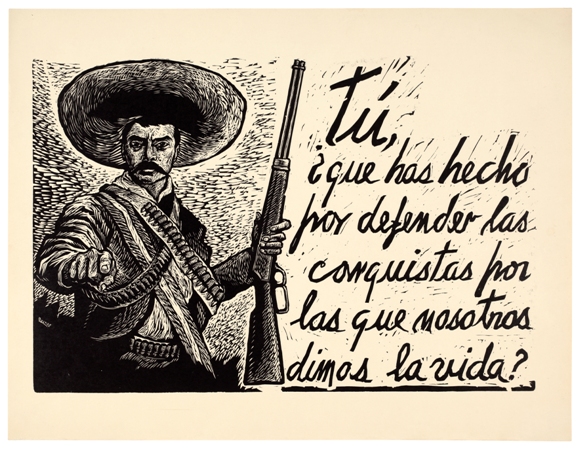

You, what have you done to defend the conquests for which we gave our lives? This question incorporated into a portrait of Mexican revolutionary leader Emilio Zapatas by master printmaker Arturo Garcia Bustos provides a compelling introduction to a selection of drawings and prints on paper by 17 notable Mexican artists, drawn from the collection of Tel Aviv Museum. Their work, produced in the spirit of the Mexican Revolution, and in a style associated with Social Realism, acts as a visual response to just this question. Working decades after Zapatas’ death, these artists harnessed their skills for the good of their countrymen and in order to press for justice and social equality.

Most of the works on display produced between the 1920s and 1950s, were printed at the Taller de Gráfica Popular (TCP) – the People’s workshop. Founded in Mexico in 1937, it was then a collective that advocated the use of art to advance revolutionary social causes. Mexico, in general, is a country with a rich history in the field of graphics, specializing in prints, posters and pamphlets that are cheap to produce and easy to distribute. The satirical, politically engaged style employed by many TCP printmakers looks back to a tradition that originated in the late 9th century tradition with the work of José Guadalupe Posada, the father of Mexican printmaking.

This link between centuries is nicely highlighted, thanks to a loan of two etchings by Posada from the collection of Moshe Gat, an artist who has lived and worked in Mexico, and was associated in the 1950s with the Socialist Realist movement in Israel. Both prints give a fair idea of the character of Posada’s work. One shows a skull-headed drunkard, the other is a ‘portrait’ of a dandy from the wealthy classes. Portrayed as a skeleton, he is nevertheless dressed in the height of fashion and smokes a cigar.

Leopoldo Méndez, one of the founders of the TCP, is represented by a number of strong pieces, all of them linocuts. This was the medium that he and many of his colleagues preferred since it enabled them, apart from its positive commercial aspect, to cover the whole area of a composition with sharp strokes, achieving a variety of tones, textures and patterns.

His linocut Corrido of Stalingrad, reveals a debt to Posada both by way of its satirical content and the introduction of skeletons that were such a feature of Posada’s work (and of the ancient Mexican Cult of the Dead.) In an expression of his opposition to Fascism, he depicts a Soviet general in the guise of a skeleton, the hoofs of his horse trampling on the skeletal bodies of German soldiers.

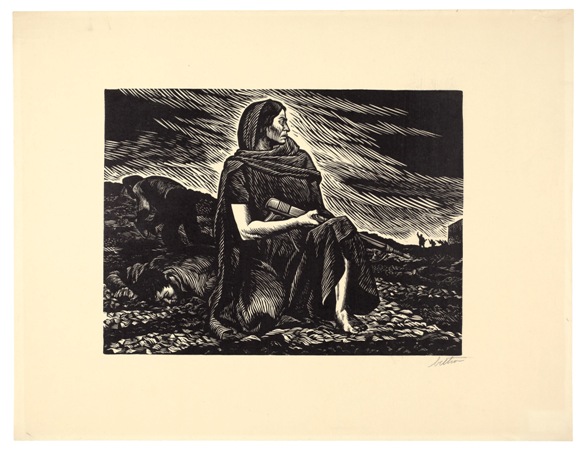

Messages relayed by other artists were also universal in character, sometimes protesting the suffering or exploitation of people living far beyond Mexican territory. This is true for Alberto Beltrán‘s rendering of Manuela Sanchez, a freedom fighter who died in the struggle against Franco’s Fascist forces in Spain. She is pictured against a blackened landscape lightened only by a halo over her head that spreads out to form lines in the sky suggesting flames. Gun in hand, she crouches on a rocky ground littered with bodies, turning her head to look at figures fleeing a building.

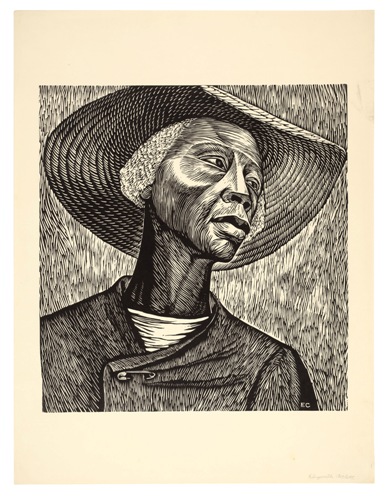

American-born artists were also associated with the TCP, among them Elizabeth Catlett, an African-American sculptor and printmaker, who lived, worked and taught in Mexico for many years. Her best known print, on display here, is Sharecropper – the reference being to former slaves who, after the American Civil War, worked on rented land for an agreed share of the crop as payment. In actuality they were caught up in a cycle of poverty. In Catlett’s print, an anonymous woman, skin rough and leathery from years of working outdoors, is transformed into a noble, heroic figure.

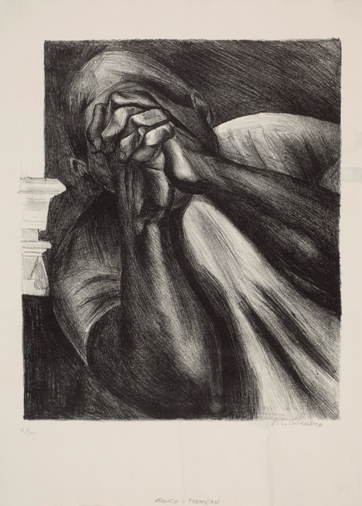

A small selection of prints by Mexico’s three greatest muralists –José Clemente Orozco, David Alfaro Siqueiros and José Diego Rivera – are also included in this selection, the most striking being Orozco’s lithograph Grief, a detail taken from his mural The Revolutionary Trinity (Mexico City 1923). Featured is a person (man or woman, its not clear) whose body leans sideways, hands locked to the front of his/her face as if to block out the reality of a situation. As Emanuela Calò, the curator of this exhibition, notes in her fine catalog text, the pillar depicted next to this grieving figure is copied from the building where the original mural was painted, thus indicating the monumental size of the original figure.

This exhibition, curated by Emanuela Calo, in the Gina and Gabriel Katri Gallery of the Tel Aviv Museum, is open until Sept. 28th 2013.