Anton Chekhov’s The Seagull is one of my favorite plays, one of those that I turn to from time to time, to read again and relive. Now Ira Avneri has reworked Chekov’s play with vigor, shaking the social drama down from ten to seven characters, in a new translation to Hebrew by Prof. Harai Golomb, working with light designer Yaron Abulafia to place an emphasis on the visual aspect of the play. The play premiered in May 2013 at Tmuna, and was presented in a festive premiere at Tmuna Theatre as part of their October Festival, showcasing the creative work of selected directors and choreographers, pushing boundaries and exploring new artistic directions.

Avneri’s adaptation is so good that I don’t really care how it compares to the original, and yet, at the same time, I left the theatre at the end of the evening feeling closer to Chekhov’s play and characters than ever before. Perhaps it is because Avneri has succeeded in tapping in to the consciousness of our time, translating Chekhov’s world of internecine relationships and desires into a contemporary environment and sensibility, one that is perhaps more visual than verbal. In stripping the play down to the bare essentials, Avneri has touched its essence.

The black box of Tmuna Theatre’s “Hanaya” – a former parking area converted into a theatre hall, makes an ideal setting for this production. There is no curtain, backstage or wings, everything is exposed. As the audience sits on folding chairs waiting for the play to begin, a woman dressed in the black uniform of stage crews everywhere emerges from a door at the back of the stage area, holding a prop: a small square white wooden stool. She sets this at the front of the stage and as she starts rolling a cigarette, almost imperceptibly begins to speak, it is as if we are listening to her thoughts: “Why do you always wear mourning? I dress in black to match my life. I am unhappy.”

The Seagull takes place in the country, at the estate of Pjotr Nikolayevich Sorin (Avi Oria), an aging retired civil servant in poor health, brother to the actress Irina Nikolayevna Arkadina (Shiri Golan). Don’t worry about the long Russian names, you’ll get used to them. The glamorous Arkadina has come to visit for a while with her lover, the successful writer Boris Alexeyevich Trigorin (Dudu Niv). In the original, the estate is cared for by Ilya Afanasyevich Shamrayev and his wife Polina Andryevna, characters who have been omitted in this version. Their daughter Masha (Michal Weinberg) is the woman in black, and her ‘monologue’ which opens the play subsumes the dialogue of her ever-disappointed beau, the teacher Semyon Semyonovich Medvedenko, who has also been cut out of the play. Avneri has made his cuts freely and wisely, taking out the more marginal characters, yet utilizing their lines to flesh out other characters and relationships.

Masha is unhappy because she is in love with Kostya – Konstantin Trepliev (Benjamin Elder), Arkadina’s son, who is at the center of this tale of love. A would-be playwright, Kostya is about to premiere his first one-act play, a monodrama starring the girl he loves – Nina (Gaia Shalita Katz), cast as the ingénue in this exceedingly self-referential play. In this triangle, naturally, Masha is the stage crew, carrying out props, climbing ladders and arranging the lights; always on the sidelines, helping her beloved without hope of recognition.

The production brings The Seagull into the 21st century without fanfare. Avneri has a knack for bringing Chekov’s subtext to the forefront, yet without belaboring the point or over-dramatizing. It simply makes sense. The costumes are current, what you’d expect people to wear at home in the country. Arkadina is in a very sexy pair of jeans, trying to look young, while Nina is pretty in pink. Kostya employs a video camera in his debut production, as befits a young playwright advocating the search for “new forms.” Nina performs Kostya’s play for the assembled guests at the estate with her back to the Tmuna audience, a close-up of her face projected on the back wall.

Don’t let the technical aspects fool you, this is not a play that plays with form for the sake of form alone; this is a play of the emotions, it’s a play with heart. The Seagull is a play about love in all its seasons, variations, disappointments and sensations; it is a play about the love of one’s art. As for the cast of The Seagull, I simply cannot praise them enough. Avneri’s adaptation and direction, in the talented performance of the actors takes the characters from lines on a page, an artificial creation that might, in less capable hands, lend itself to mere caricature or cliché, a stage image distant from the audience, to another realm altogether. For that space of time, they become real, and one becomes acquainted with them, their desires, vanity, fears, petty jealousies and heartache. These are people one comes to know, and by the play’s end, one feels for them, and each, from the most foolish to the most contemptible among them, has, if only for a moment, invited one’s empathy.

Masha may be downtrodden and depressed, yet she is also keenly self-aware, and Michal Weinberg succeeds in conveying a fighting spirit within the very constrained margins of her lowly existence. Sorin is loveable from beginning to end, Avi Oria makes this humdrum civil servant into a hero of the small moment, imbuing him with life and warmth. Gaia Shalita Katz brings a refreshing sincerity and intelligence to Nina, and Shiri Golan delivers a highly amusing Arkadina, while revealing the vulnerability beneath the thin veneer of beauty and fame. Benjamin Elder gives Kostya room to grow within the play, from a self-absorbed young man to one who may never quite conquer his emotions, yet has acquired a greater awareness of others. Yoram Yosephsberg’s Dr. Dorn is quite the suave fellow with his deep voice, one is easily convinced that he won many a lady’s heart back in the day.

Trigorin, ah, Trigorin. Without Trigorin, really, there would be no drama, yet I’ve never really understood what Nina sees in him. Dudu Niv has changed all that. Niv is the sexiest Trigorin ever, bringing a geeky allure to this character with his soft spoken voice and quiet manner. Don’t get me wrong, I still hate the dude for being such a duplicitous sleaze-bag, but in Niv’s intelligent and penetrating interpretation I’ve come as close as I possibly can to understanding Trigorin as a writer and as a fellow, fallible, human being.

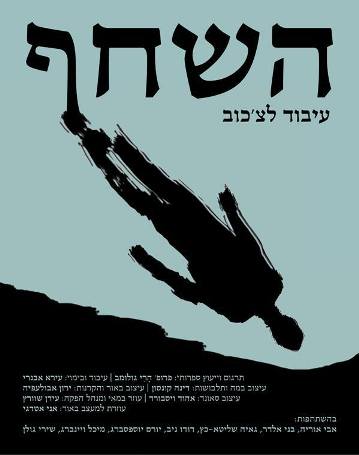

The Seagull by Anton Chekhov

Translator and literary consultant: Prof. Harai Golomb; Adaptation and direction: Ira Avneri; Costume and set design: Dina Konson; Lighting design and projection: Yaron Abulafia; Sound design: Ehud Weissbrod; Assistant director and production manager: Idan Schwartz; Assistant lighting director: Ani Ategi; Lighting: Amihai Elharar; Cast: Avi Oria, Shiri Golan, Benjamin Elder, Michal Weinberg, Gaia Shalita Katz, Yoram Yosephsberg, Dudu Niv.