Classic cinema, it should be said, does serve a higher purpose than filling television schedules on wet Saturday afternoons. (Not that I’m knocking this completely; my familiarity with Hitchcock is largely due to the vagaries of the British climate; that and the awkward mid-afternoon slot on Britain’s BBC2, with lots of spare airtime and no live sports to show.) Classic cinema is in many ways the oral (and visual) literature of our age, the prompt that there really is a causal connection between the past and our present.

Running for a second year at the Tel Aviv, Haifa and Jerusalem Cinematheques, Another Look: The Restored European Film Project works to encourage engagement with the depth and range of classic European cinema. It also, beyond this, highlights the importance of cultural preservation; think about it as a living museum of sorts, a multifaceted audiovisual archive, a reminder that our political and social concerns are not necessarily unique to our age.

This year, the selected films have been curated along two interlinked strands. Facing the Real, as the name suggests, contemplates how filmmakers have confronted social, political and psychological concerns in uncompromising fashion; a look at the cradle of social realism in cinema, one could say. By contrast, Flights of Fancy embodies a certain whimsy; avoiding direct confrontation, films that rather using humour and irony as tools for social commentary.

The Fireman’s Ball is an excellent example of the latter. In a small Czechoslovakian town, the local fire department’s management committee are trying to arrange a party to celebrate the 86th birthday of the former chief. Things go awry from the start. Someone is stealing the gifts earmarked for the raffle at the end of the ball; the decision to crown the evening’s festivities with a beauty contest veers between the misconceived and the tawdry. And then there is a small matter of everyone except the ex-chief himself knowing that he is dying of cancer…you know the old insult about the guy so incompetent, he couldn’t arrange a piss-up in a brewery? Well, these fellows couldn’t put out a fire even if were right above their heads. Literally.

Milos Forman is best known for films that portray flawed everyman fighting the system – Jack Nicholson’s McMurphy in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Woody Harrelson as pornographer Larry Flynt in The State Vs Larry Flynt, Jim Carrey as the irascible Andy Kaufman in Man in the Moon. This observation piece dates back before all these though, made in 1967 in his native Czechoslovakia. On the surface, it is gentle, absurdist humour; scratch a little under the surface though, and a satirical undertone becomes apparent, a merciless send-up of communist corruption and inefficiency. The film was quite prescient in tone, considering the outbreak of the Prague Spring (and its violent suppression) the year after its release. In any case, it seems that Forman did not disguise his intent enough – or chose not to – as The Fireman’s Ball was banned in the Eastern Bloc for many years, and Forman was effectively forced into exile. Our gain, one might surmise.

Romania’s A Bomb was Stolen, from 1961, thumbs its nose at the establishment, and in this sense shares the same satirical DNA as The Fireman’s Ball. But there is a darker element: the threat of nuclear annihilation, social deprivation, the indistinguishable culpability of professional criminals and the military. Oh, and a love story, just to mix things up a bit.

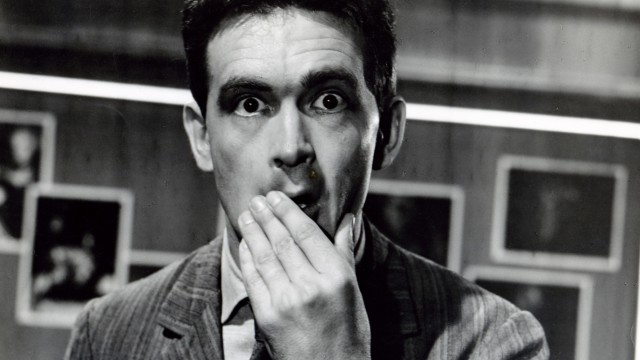

Ion Popescu-Gopo, animator and film-maker, made this silent film in the shadow of the Mutually Assured Destruction military principle of the Cold War. (Take a moment and think about the acronym of the principle. Please.) Our hero, a nameless everyman out of work and down on his luck, accidentally takes delivery of a stolen atomic weapon in a briefcase. Cue slapstick chases, as both the military police and thieves try to retrieve the goods with setting the weapon off. But the humour is tempered by a disturbing mise-en-scene, suggesting a moral and social corruption that somehow puts the trifling matter of a nuclear bomb in the shade. After all, if our hero drops his package accidentally, we’ll all be wiped out and that will be that. Poverty and deprivation don’t go away quite so easily.

Hunger, the 1967 film based on the book of the same name by Knut Hamsun flips the emphasis of A Bomb is Stolen: Social realism is the dominant key, absurdism the minor. Pontus, our principal, is a struggling writer who doesn’t seem to get very much writing done. (To be honest, this sounds a little familiar.) Instead, he wanders the streets of Christiania (today Oslo), seeking inspiration and salvation from a world he is ill-equipped to negotiate. The superiority complex that many writers seem to embody can also often be the trigger for their downfall. (Again, this sounds uncomfortably familiar.) Pontus’ arrogance bequeaths him a sense of noblesse oblige, the feeling that his privilege demands concomitant social responsibility. Truth is, his naturally abrasive temperament doesn’t help very much. And with scarcely to pennies to rub against one another, he’s fairly lacking on the noblesse front. It is this disjuncture that spells his doom; too proud to ask for help, he subsides into a twilight of mental collapse. His only anchor with reality is infatuation with fragrant Ylajali, but the chances are, this will remain unrequited…

Directed by Henning Carlsen, Hunger is considered a masterpiece of social realism. It is also, I think, a sobering cautionary tale: There, but for the grace of God (or whatever deity one subscribes to) go us all. Community, camaraderie, the simple luxuries of friendship and support are immensely important props on the journey through life. Without them, like Pontus, we would all be lost.

Chantal Akerman has the unusual capacity of turning the camera into a confrontational tool just by its simple presence. News From Home, filmed in the summer of 1976, is an audio and visual reconfiguration of her experiences when she first moved to the United States in 1971. The leitmotif is a static camera, capturing seemingly random scenes: the platform on a subway, a street corner, kids playing ball, the middle of the street. By doing nothing, she forces her anonymous respondents into doing something. The camera can never be overlooked, I think. All the while, she reads letters sent to her by her mother, enquiring after her welfare and keeping her up to date with the quotidian detail of everyday life in Belgium. The news from home, which ebbs and wanes as Akerman embeds herself deeper in her new home.

News From Home is a surprisingly beguiling film. Nothing really happens, after all. At least so it seems. There is a lot to contemplate, as it happens: the hypnotic quality of the ambient soundscape, the existential concern for Akerman’s accidental characters, even the unusual sight of a run-down New York, far from the glittering metropolis we all think of today. it is not conventional film-making in any sense, but if one allows it even a few moments, it begins to pull one insistently into reverie. Which, I suppose, is as good a reason as any for projects like Another Look. By removing us from the insistence of the moment, it affords us a small space to think.

Another Look: The Restored European Film Project #2

15-31 January, 2014, at the Tel Aviv, Haifa and Jerusalem Cinematheques

A full list of films and a schedule can be found at www.anotherlook.co.il