In an unformed (perhaps uninformed?) way, I’ve always assumed that the thing that we call consciousness – you know, that inchoate sense of self that distinguishes us from animals and inanimate objects, along with the capacity for waging unlimited warfare – is nothing more than the consequence of our complicated neurological make up. Or to put it differently: once computers are able to replicate, in complexity and depth, the mess of neural pathways and synapses that constitute our sensory make-up, they will become sentient. And we, my fellow humans, will become toast.

This isn’t quite the point behind Her, the brilliant new movie by Spike Jonze, but it isn’t very far away. Her, in its essence, is a relationship movie operating on two notionally distinct planes at the same time; exploring the human capacity to form meaningful emotional relationships, and exploring the intellectual relationship between man and technology. The two are related, though, and in more ways than you might suspect. If nothing else, neither relationship is fully informed by the mutual appreciation of conscious independent thought.

But that’s by the way. Her is set in the near future, a strangely familiar yet vaguely unreal landscape. (Exteriors were shot in Shanghai; therein lies the future, boys and girls. Brush up on your Mandarin now.) Theodore Twombly (Joaquim Phoenix) crafts personal letters for people less in touch with the poetic in their everyday lives. Nice work if you can get it, I suppose. But his talents haven’t served him well in his own real life; his wife, Catherine (Rooney Mara), is about to become his ex, in part because he is too buttoned up and unable to say the simple things that lovers say to each other. His world is, all things considered, a rather antiseptic experience, the sterile silence in his head and his heart broken only by video games and a passive friendship with neighbour Amy (Amy Adams) and her passive-aggressive husband Charles (Matt Letscher).

One day, on a whim, he downloads a new operating system, an OS, for his…his computer? His phone? His interconnected virtual life of emails and voicemails and reminders and wake up calls? It doesn’t matter. The OS is a she, and her name is Samantha: funny and friendly and a little bit sassy, she denies complete intellectual autonomy, but doesn’t seem to be far off it. For many men of a certain age, she could be the perfect date. Keep in mind the fact that Samantha is voiced, to arch perfection, by Scarlett Johansson; I think it’s fair to say that this would be a done deal for lots and lots of us very quickly.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Her isn’t as simplistic and as straightforward as your conventional boy-meets-OS-falls-in-love-with-OS-has-lots-of-mini-OS-offspring movies. For one things, Theodore is sentient but not entirely rational. He holds off on signing his divorce papers because he does want Catherine back – doesn’t understand how he lost her, actually. Samantha, on the other hand, has the uber-rationality of Mr. Spock but the incorrigible curiosity of a small child. She sifts through Theodore’s emails and tells him which ones are worth keeping; she laughs at his jokes, and nudges him into going into a blind date, all the better to work Catherine out of his system. It doesn’t work, of course. Theodore simply can’t find space for another human being in his emotional make-up. But that doesn’t discount other possibilities…

Most films that try to project a vision of the things to come wind up shaping either utopian or dystopian visions of the future. Her avoids the partisan pitfalls of both, instead creating an intriguingly honest portrait where it is not our social concerns that have changed, but rather the infrastructure with which we manage them. Samantha has the capacity for psychological – and thus, emotional – growth. It really is just a small leap of imagination to imagine falling in love with an OS that can respond to one’s needs with a sensitivity and passion that many humans lack the emotional language to articulate. (Look at it this way: I can still remember when jdate.com and the like were considered the sanctuary of the desperate and the socially incapable. And this wasn’t that long ago, either.)

The problem though is with sentient thought – or even a close approximation of same – comes all the doubts and anxieties and reservations that plague humankind. It isn’t the emotional tension between Theodore and Samantha (coupled with Catherine’s disbelief, and Amy’s enthusiasm) that lifts Her above the quotidian; rather, it is the accurate, disconcerting and yet non-judgemental mirror image of our own lives that the film creates that resonates.

Her is a beautiful film, both aesthetically and intellectually. Jonez’s script (nominated for a best original screenplay Oscar last week) is clever without being flamboyant; the world on whose behalf it speaks is, in many ways, not hugely dissimilar to the familiarity of our now. You and I, once we have made some fundamental adjustments to our wardrobes and our use of smartphones, will feel very much at home there. It seems to me that Jonze, very subtly but insistently, makes the point that at some point we will conquer technology; it will become a tool, and no more, to help us live better lives, rather than the pivot that establishes the difference between the normative and the not.

Even so, this vision of the future – whilst an integral aspect of Her – is a bit of a red herring. Her is a piece of theatre about whether one day man will learn to love machines, or a machine. But it is much more about whether one day, man will actually remember that it is possible, permissible to love anyone other than oneself.

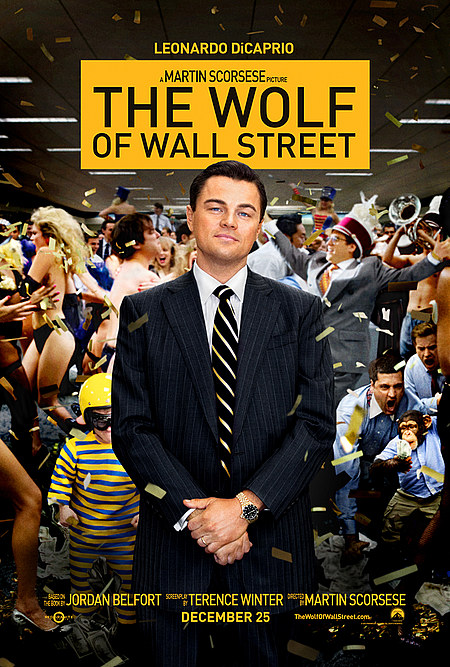

From the future to the not-too-distant past, and with a health advisory warning: The Wolf of Wall Street is not a film for people with a sensitive disposition, nor is it intended for anyone still filled with righteous anger about the Great Financial Collapse of ’08.

Jordan Belfort, he smugly informs us in voice-over at the beginning of the film, made $49m in the year he turned 28. This actually pisses him off a bit; $3m more and it would have been an even million dollars a week. Never mind, he finds ways to put the money to good use. Debauchery in and out of the workplace, epic encounters with coke and alcohol, an addiction to Quaaludes. Easy come, easy go, one might surmise. Belfort makes his money from the time tried-and-tested stock market technique of “pump and dump”, artificially inflating the prices of worthless stock and then selling it on to the unsuspecting public for a lovely profit. He is one part high pressure salesman, three parts carnival huckster. Belfort clearly subscribes to P.T. Barnum’s philosophy; there’s a sucker born every moment, and he has made it his life’s work to hunt them all down.

The Wolf of Wall Street is deceptively simple. Boy discovers money markets, boy makes increasingly inventive use of the vast amounts of money he siphons off from said money markets, boy tries hard not be caught with his hand – no, make that his whole body – in the till. The main problem with the last is that when one has developed a world-champion appetite for drugs, alcohol and generally debauched living, caution and discretion are not exactly at the forefront of one’s consciousness. Belfort quite likes being the Wolf of Wall Street, as a supposedly unflattering profile in Forbes magazine labels him. But even the wolves get culled occasionally.

There is the argument that the banking “crisis” ought to be considered only within the context of the vast harm wrought upon the global economy by the greedy, grasping money men in firms like Belfort’s Stratton Oakfort. I beg to differ. For one thing, there’s no point in crying over spilt milk after the horse had bolted, or any other mixed metaphors that you fancy. There was a time and place for sober exposes about Wall Street, and this was a few years ago – either as a warning (take Michael Lewis’ Liar’s Poker, for example) or as explanation (Alex Gibney’s Oscar-nominated documentary about Enron, The Smartest Guys in the Room). The Wolf of Wall Street is neither. If one wishes to be philosophical about these things, we could go down the “holding up a mirror of our age” explanation, the reminder that there but for the grace of bad lack go us all. Alternatively, one can shrug one’s shoulders, forget about searching for morality in the babbling brooks and accept it as a bloody good piece of entertainment.

Personally, I veer towards the latter. Martin Scorsese has become decidedly less ponderous in recent years, and The Wolf…captures an astonishingly misdirected joie de vivre. It’s partly the scene set-ups: more than once, you’ll catch yourself gasping in disbelief. It’s partly the script, adapted by Terence Winter, of Broadwalk Empire fame, from Jordan Belfort’s autobiography. (Yes, he is real. And, somehow, still alive.) It’s partly Thelma Schoonmaker’s editing, pacing the 3 hour film perfectly.

But the best of the film comes from the acting; from an inspired, off the wall cameo from Matthew McConaughey, through solid support work – largely against type – from Jean Dujardin, Margot Robbie and Jonah Hill. The last, as Belfort’s right hand man Donnie Azoff, is the most amoral thing you’ll ever come across, I hope. He’s magnificent.

And then, there’s DiCaprio. DiCaprio’s recent choice of films roles has been a bit wobbly in the recent past. Here, he…well, he is the life and soul of the party. Literally. Jordan Belfort made a few people (besides himself) very rich, and many more a little bit poorer, or worse. DiCaprio helps one understand how. Whether he is rallying his troops to go forth into battle – or to sell over-hyped and over-priced shares, which he just happens to own, illegally – or charming a telephone client into parting with money for nothing, he is mesmeric. Hypnotic. It’s the best thing he’s done with Scorsese, possibly the best thing he has done, period.

Her

Written and Directed by Spike Jonze

Starring Joaquim Phoenix, Amy Adams, Rooney Mara and Scarlett Johansson

126 minutes, English w. Hebrew subtitles

The Wolf of Wall Street

Directed by Martin Scorsese, written by Terence Winter

Starring Leonardo DiCaprio, Jonah Hill, Margot Robbie, Rob Reiner, Matthew McConaughey, Jon Favreau

180 minutes, English w. Hebrew subtitles.