The Mystical Shabbat, a virtual installation created by Israeli artist and filmmaker Maya Zack is currently showing in Tel Aviv. It is also on permanent display at the Jewish Museum, Vienna. Why are these facts mentioned at the start of this review? Because the core inspiration for Zack’s’ piece is the history of this particular Museum and, amongst its collection, a particular work by Hungarian-Viennese artist Isidor Kaufmann.

Kaufmann (1853-1921) is primarily remembered for his portrayals of life in the Chassidic shtels of Eastern Europe, folk paintings that were popular with the Jewish bourgeoisie of fin de siècle Vienna serving to remind them of their religious heritage. But of equal importance at the turn of the century – a time of religious enlightenment and public curiosity as to the lifestyles of different ethnic communities – was Kaufmann’s Shabbat Room, known as the Gute Stube. (1899). A travelling installation, it was exhibited at Jewish and non-Jewish venues in Austria and abroad before entering the collection of Vienna’s Jewish Museum. But its ‘wanderings’ did not cease there: between 1899 and 1911 the Museum and its contents changed location several times before moving to 6 Malgzasse, in the center of the city where it remained open till 1938. This was the year that the Nazis closed the Museum transferring its contents, including Kaufmann’s installation, first to the Natural History Museum and then to the city’s Museum of Ethnology where it served as a tool for anti-semitic propaganda.

Zack’s aim, effectively achieved, was to breathe new life into Kaufmann’s installation. Her vehicle: three large computer-generated prints (viewed through 3D spectacles) that are imagined reconstructions of the Gute Stube, at various stations on its travels. One of these is The Shabbat Room 1: Malzgasse 16 into which, as in all her staged environments, she has introduced furniture and ornaments identical to those in Kaufmann’s original installation, or in décor found in his paintings. But she has also introduced some meaningful imagery of her own into this scene. A packing case on the floor and others stacked on a high shelf hint at the further ‘journeys’ that the Gute Stube would be forced to take; while the presence of a glass showcase alludes to the fact that the handful of objects (10 out of 122) in Kaufmann’s original room that survived the Holocaust – – among them a candelabra, a spice-box, a broken vessel – are now on permanent display in Vienna’s new Jewish Museum.

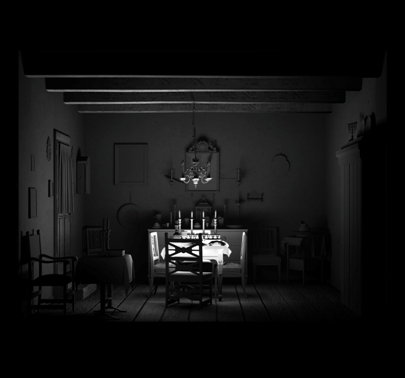

Zack’s has also introduced a painter’s easel into this interior. On it are ghostly traces of Friday Evening (1920), perhaps Kaufmann’s best known picture, now in the collection of the Jewish Museum, New York . In this composition, a woman sits alongside a table prepared for Shabbat (perhaps awaiting her husband return from synagogue). The candles on the table are lit but their light, as reflected in the mirror on the wall is transformed into wreaths of smoke. Identifying with Kaufmann’s attempts to make visible aspects of Chassidic belief is Zack’s fourth frame, whose title gives this exhibition its name. We see a room in darkness, the only illumination: the light that rises up from the Shabbat table.

A memorable exhibit that reaffirms in a highly imaginative way the continuity of Jewish life and thought.

Till March 28th, Alon Segev Gallery, 6 Rothschild blvd, Tel Aviv