If you’re going to take risks onstage, be prepared, be precise, and be powerful. Qualities the works presented in Intimadance 2016 all possessed, which is saying a lot for a festival of 11 new works. Under the artistic direction of Tal Yahas, Yair Vardi and Nava Zuckerman, Intimadance 2016 took place from July 21 – 24, with the theme “The Rules of the Game,” inviting choreographers to explore the changing rules of the game in the current Israeli social-political-cultural scene. Tmuna always takes a ‘total’ approach to the festival, utilizing all or most of the different spaces within the venue, and creating a theme-based program. This year, Ruth Gvili designed a wonderfully expressive visual concept for the festival and playful program, creating a new game for each dance piece. Visitors to the festival received a sharpened pencil along with the program – what better invitation to join the game?

Illuminated from above, striding on treadmills positioned in a circle, were Tal Alperstein, Tal Adler Arieli, Iyar Blomberg, Raz Gluzman, Merav Dagan, Nir Segal and Yehonatan Ron dressed in pastel hues of pink, yellow, blue, orange and green. Kol HaHalichonim MeYuashim (All the Treadmills Despair – a play on words in Hebrew as MeUyashim means ‘manned’ or ‘occupied’ while MeYuashim means ‘despair’) was a focal point of the festival. The official performance was in program Bet, but the treadmills and walkers were present throughout, with two empty treadmills for audience participation.

Visually compelling, the rules for this work were very precise. Microphones connected to the treadmills were activated by achieving running speed, in order to speak, one must run; if one runs, one must speak. Exploring the connection between speech and the body, the physical experience of discourse, this was a fascinating work. Immediately bringing to mind the caucus race in Alice in Wonderland, a multitude of issues and associations arose while watching the mesmerizing scene. The six characters in search of conversation exhibited magnificent endurance during the synchronized running, walking and interludes of romantic and playful treadmill choreography: “let me hear your body talk.” The performance centered on conversations about the future, with audience members invited to join in. A few brave souls ventured forth while I watched (I really wanted to join, but was too scared) and a very open, welcoming, and honest exchange took place, with exacting insistence on abiding by the rules. Watching the runners going nowhere fast, talking about the future, I pondered the connection of thought to breath and effort. In a social-political arena where whatever is said becomes truth, and words – whether written or spoken – are propagated with ease, the need to make an effort is intriguing to contemplate, literally requiring one to be ‘fit to speak.’

At the other end of the verbal spectrum, intensely physical and thought-provoking is Joel Bray and Oded Ronen’s Mechonot Shel Od (Machines of More – my translation from the Hebrew). The two spectacularly fit dancers explore the competitive world of dating (sex) apps and its scripted exchanges. Megaphone in hand, Joel Bray calls out – Ma HaMatzav (what’s up?), Are you still here? Sexy! etc – and Oded Ronen assumes the appropriate position. The sex chat is a warm up for a hyperbolic bragging session, with the uneasy equation of professional, financial and sexual success. These guys are clearly on top of their game, but then, the pace and mood shifts, one can almost see their bodies become somehow softer, more vulnerable, as childhood memories and tender longings emerge. The merging of text and movement in this hard-hitting piece, as well as the structure and pacing is meticulous. Just as one is drawn into a tender moment, the game is on again, as Ronen turns to the audience with a winning smile and irresistible offer; while in the background Bray flounders, lost.

Adili Liberman recreates the lecture/performance of Jean-Martin Charcot’s ‘Living Pathological Museum’ (Charcot’s term) in Mofa’ei HaHysteria (the Hysteria Shows) – in a harrowingly chilling performance that is terribly entertaining. Liberman, abundantly pregnant (bravo on the perfect timing!), takes on the role of the lecturer, informing the audience in a seemingly neutral tone of Charcot’s research and demonstrations of hysteria as a female pathology. Meshi Olinky , Karmit Burian, and Maayan Horesh in their demure Victorian gowns portray the stages of affliction, cued into action by pressure on the salient points of the body. Revealing the eloquence of the body as its speaks its suffering and desire, writhing, contorting, and ultimately reveling in its own power, finding an alternative path beyond the boundaries of an oppressive restrictive society.

While the contemporary perspective on Charcot understands his work with female patients as ignorant and confused at best, and verging on abusive, it is also instructive to consider that his neurology clinic at Salpêtrière was a respected place of research in its time, and Charcot is credited with identifying and describing multiple sclerosis and other neurological diseases. The most sinister aspect of his work with these “hysterical” women is that it took place under the auspices of legitimate scientific research, solidly within the guidelines of the scientific practice and discourse of its time. One might well view Liberman’s work as a challenge to examine the accepted tropes and forms of discourse in our own time.

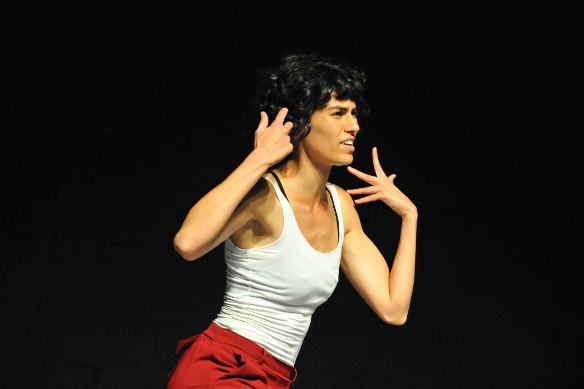

These works resonated most for me, yet all the works presented reflected a significant conception, process and execution. Tami Itzhaki took an exacting physical and emotional inventory of the body, its history and its future. There was a striking dissonance between the fluidity and precision of her movement and the spoken text enumerating the scars and vulnerabilities of the body, the bright fragility of its wishful future.

Ella Rothschild inhabited the post-traumatic raft of Nivi Elroy’s creation with survivor elegance, plumbing the artifacts of ruin and eking out an existence with no future visible on the horizon.

Noa Mark-Ofer braves a death-defying balancing act on the exposed cliff-face of parenting/mothering as it is rarely expressed in public discourse: the experience of becoming a mother to a child with special needs that must be fulfilled in an extremely precise manner to ensure his survival. Created by Noa Mark-Ofer and Dana Ruttenberg, with dramaturgy by Renana Raz, this work explores with sensitivity and compassion what happens when the rules of the game change all at once.

Maayan Cohen-Marciano performs the conflicts of an identity formed in the struggle between conflicting cultures. She embodies the tensions between Bach and Fairuz, the necessity and pleasures and resentment of assimilation in the dominant culture, the feelings of betrayal, the fear of not fitting in, the fear of fitting in all too well. There are some lovely moments here, especially in the dissonance between the music and the movement.

Dror Liberman and Kazuyo Shionoiri present a violently physical manifestation of the independent artist’s fight for survival in Here Comes the Hit (speaking of games – nice play on words). The two wrestle with impressive physical prowess and impeccable timing in an arena governed by unspoken, unwritten, yet very emphatic rules.

At the other extreme is Rotem Tashach, who has established a signature form of lecture/performance. An articulate, amusing, text is accompanied by an illustrative and evocative movement language, as he questions, probes, and provokes. Questioning the place of art, the relationship of art and its ability to influence the social-political arena, the consumption of world events – war, the plight of refugees – as entertainment, art as a means for social-political expression and change, art as escapism; Tashach analyzes, discusses, and calls into question specific examples from the Israeli dance scene. It’s highly provocative, yet he does not exempt himself and his own work from this disturbing reflection. It is, perhaps, most fitting that this work began with the question posed in Carole King’s song: “Will you still love me tomorrow?”

The ultimate, perfect, guest performance for this year’s festival was Yossi Berg and Oded Graf’s Come Jump with Me, performed by Yossi Berg and Olivia Court Mesa. A clever, entertaining and eviscerating exploration of Israeli existence, with outstanding performances by Court Mesa and Berg, one finds in this work many echoes and refrains from themes raised in “The Rules of the Game.”