Intriguing, disturbing, inspiring, exciting, inciting, sometimes annoying, and unexpectedly tender – that is A-Genre for me. This year’s theme was Home Sweet Home, co-curated by Artistic Directors Nitzan Cohen and Nava Zuckerman; with producer and assistant curator Tali Konigsberg. I saw both programs, back to back, immersed in the performative space that is Tmuna Theatre.

Let’s begin with intriguing…

In the bar, my eyes first met a bed of knives, surrounded by assorted tools and zip ties on the ground. I’m wondering: who is the prisoner? As What a Beautiful Day, created by Shimrit Malul and Iris Mualem, took shape, people helped insert all the knives into the slots, anchoring them with the zip ties, as two plates of nuts, dates, and a plate of tomatoes rested on the steel bed. Eventually, the food was removed and Shimrit Malul lay on the bed, as Iris Mualem placed the following sign on either side of the bed: “love is like a king who rules himself and I am ruled by passion/I will do as it tells me. What a beautiful day.” Shimrit ate of the tomatoes, juice running down the corners of her mouth, impaling them on the knives. A flowered cloth had been placed around the lit bed by Iris Mualem, making it resemble a funeral bier. Removing her dress, in the end, Shimrit lay nude, knives bound to each hand, her hands flailing, armed and helpless, unable to retrieve a thing. A striking, visually compelling work. Body as home of passions, meeting at the intersection of pleasure and pain.

Greeted by the warm scent of delicious food, four at a time, visitors entered the theatre’s tiny kitchen, where Yuval Meskin and Leslie Granot conjured an experience of memory, pleasure and the prick of awareness. Like Proust’s madeleine, the aroma of cooking evokes in me everything I felt as a child in my grandparent’s kitchen, surrounded by love and the expectation of something delicious. Memories of a more innocent time. Leslie moved with the grace and easy swiftness I recall, creating culinary wonders. On the menu: songs from Yuval’s childhood, written in his private code, which we could choose from. I chose Elvis Presley, and heard a lively rendition of something I remember from my own schooldays – inventing different words to a popular tune. The other songs touched on more somber notes. Kita Almonit http://www.zemereshet.co.il/song.asp?id=4418 (lyrics: Yehiel (Ali) Mohar, music: Moshe Vilensky) sings of soldiers marching near the border with a flame burning in their hearts and love inscribed on their banner, or Kadru Pnei Hashamayim http://www.zemereshet.co.il/song.asp?id=1665 (lyrics: Yehoshua Proshansky, music: Russian folk song) with its offering “Hills of Ephraim receive a new, young, victim.” I was struck by the violence they enfolded, the unquestioning acceptance of death as a way of life, to defend one’s home. Songs sung by Yuval as an eight-year-old, revisited. Childhood and its innocence re-visioned with older, watchful eyes. That is one of the complexities of home, that the love, comfort, and fun, can also be interwoven with conflict.

Transforming the personal into a work of art is an elusive pursuit. In A-Genre, there were two creative artists who made that leap from immersion in the minutiae and artifacts, the raw material of their own lives, into a work that communicates and resonates with those intimate strangers, the audience: Nadav Bossem and Alit Kreiz. Another quality shared by these two very different creator/performers is the wit and humor of their work, the symbolic equivalent of a jetpack, propelling them instantly into my welcoming mind.

Alit Kreiz invited the audience to join her on the ample stage where yellow tape marked out the floor plan of her current apartment. Little did I realize at first, to what extent we all really were part of the show. Riffing on her considerable list of former addresses, she closed with the statement: “there was not one of those apartments in which I lived with a partner.” From there it was almost a natural next step to ask the rest of us: “Who lives alone?” There was a show of hands. “Who wants to live with someone?” The questions continued to come, with Kreiz sending people to different rooms of her home according to their answers. Certain answers resulted in being sent offstage, to sit down and become observers once more. As the questions went on – “Is it important to you to stand up for your opinions?” – and the number of people still onstage grew smaller, it slowly dawned on me that this was more than a lively meditation on identity and the choices we make about how to live our lives, with the rooms of our house as a kind of metaphor for the affinity we feel towards others, how close we might feel to some, and distant from others. This was a search for a life partner in real time, with questions ranging from philosophical to nuances of feeling: “Do you notice when someone cuts their hair? Even if it’s just a trim?” Throughout, Kreiz displays a fascinating hold on her audience, creating a scene in which she has total control, because she understands the power of the unexpected, and makes room for it.

Nadav Bossem ventured into the innermost chamber of the theatre, the cycle, and there erected a memorial installation/performance dedicated to his mother, who died last summer, on July 26, 2016. In a manner similar to museum curation, the objects and artifacts from his mother’s apartment were displayed in the space, dresses, letters, books, records and other paraphernalia, the trivial and the intensely personal, with a view of her kitchen projected on one wall, and the image of floor to ceiling bookshelves on the facing wall. A beautifully designed set of cards (reminiscent of educational card games popular in certain Israeli homes) enabled visitors to play the game of Nadav’s mother’s life, with images of her childhood in Brooklyn, or favorite films.

The mother’s body is our first home; our concept and memories of home are formed by those who raise us. When a parent dies, that home is taken apart, both figuratively and literally. What is to be done with all the objects we leave behind after our death? Can one reconstruct the individual from what remains? This intense scrutiny, macabre, intrusive, funny, and insightful, felt like a way for Nadav to hold on, and to let go. It was a strange and moving experience, a wry celebration of a woman’s life with all her determination, passions, and quirks. After spending some time in the exhibit, I felt that I knew this woman I had never met. Although I can’t quite forgive the way she voted in 1977, I like her.

Noga Golan performed a dance in the bar – large, asymmetric, free movement, moving on different levels, with nuanced, articulated hand gestures. Then she turned on the monitor to show the origins of the dance: in her own uninhibited, free dance as a child, unfettered by genre, dance schools, or the gaze of the world. A vision of home as the urges of one’s own primary thoughts, feelings, movements.

Maayan Cohen Marciano performed in the bar, a dance whose initial movements were so repetitive and minimal that made it difficult for me to enter at first. Yet the intensity of her performance, the extent of her control, use of body percussion, and the inventiveness of her nuanced movements as the dance developed, drew me in.

Anna Zakarevsky’s work remained somewhat opaque for me, yet had a compelling visual allure, as well as a sense of the immigrant’s chaotic internal homelessness in which neither the country of origin, nor one’s adopted country is home.

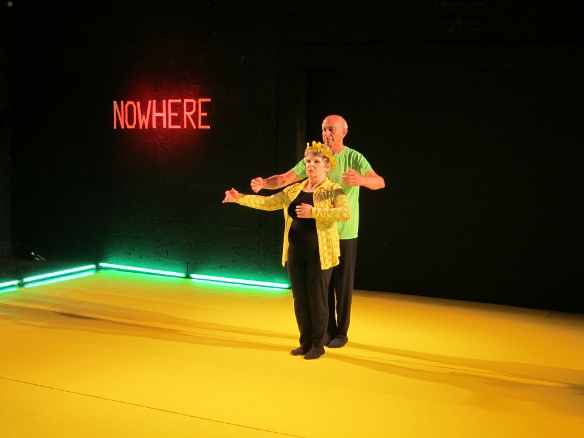

Galia Einey in a sense brought her home into the theatre – she threw her parents into the turbulent waters of performance, where they swam admirably. Anyone who takes the stage takes a risk, a big one, and it takes a lot of courage. The two performed a minimalist choreography while a soundtrack conveyed their self-introduction, and a conversation on performance art in general, as well as the one they were currently performing.

A small room with a large glass window facing the bar was the set for two very different works which the audience could observe from beyond the window. During one program, audience members could enter the room for a consultation with Ayelet Ben Zvi on designing the ultimate (as in final) home – their gravestone, while Ruti Shapira sketched out their ideas. Their conversation was conveyed to the outer area via the sound system. I heard fragments of conversation: “I hope to accomplish in my lifetime the things I set out to do, and what I do not manage to do [before I die], I accept that.” In the other program, the room was bare except for a single floodlight and a chair. Oded Liphshitz created an evocative, very open-ended text, that was narrated over the sound system, while actor Michal Weinberg performed different scenes to the accompaniment of the narration, creating layers of interpretation and feeling. The repetition of the looped text felt a bit frustrating for me, I love a good mystery, but I also really enjoy resolution. Michal Weinberg was mesmerizing, magnificent tour de force of metamorphosis – by turns queen of cool, seductive, mysterious, desperate.

The theatre’s foyer was dedicated to an unusual photography exhibit that had no photographs. Spotlights illuminated the blank wall, and each space had its label neatly marked, indicating the photograph’s title, date, and photographer. Yet for many of these photographs one did not need the physical presence to see the image in the mind’s eye: these were iconic moments, images imprinted on the collective cultural memory. Lunch atop a Skyscraper, with eleven men sitting on a girder high above the streets of New York, taken in 1932 and attributed to Charles E. Ebbets, John Lennon and Yoko Ono in their 1969 Bed-In in Amsterdam, and images of war: Roger Fenton’s Valley of the Shadow of Death taken during the Crimean War, the 1972 photograph taken by Nick Ut in Vietnam of the nine-year-old girl running with severe Napalm burns on her back, an Alan Kurdi, the three year old Syrian boy photographed lying dead on the Turkish shore in September 2015. These images are familiar to us, perhaps too familiar. Do we really see them? Or have we become so desensitized by the proliferation of images, and the safe distance of the various screens in our lives.

Relationships, history, geography, memory, body, and the body politic all came into play in Nofar Sela’s very engaging interactive performance. Invoking deep-rooted cultural memories, Sela whistled the tune to Shaul Tchernichovsky’s (1875 – 1943) poem: “They say there is a land/a land drenched with sun./Where is that land?/Where is that sun?” She cheerfully indicated that the audience is invited to join in and whistle along. Beginning by creating the map of Israel with her body, much like Israeli tour guides do for schoolchildren, Nofar led a warm and lively conversation with the audience. Drawing the map of Israel with coal on paper, she sought the precise locations of places, asking questions to evoke the memories, feelings, and associations.

Taking on the persona of the land of Israel, she asked: “Am I beautiful in your eyes?” and “What do you find beautiful about me?” More questions followed: “Do you love me the way you used to?” “Do you ever think about leaving?” Utilizing the language of romantic relationships to examine our relationship to the land of Israel was both engaging and provocative, encouraging the audience to respond openly and without inhibitions. Sela’s use of dialog was playful, witty, pointed, and precise. Locating Gaza on the paper and charcoal map, describing it as resembling a hand, she tossed around some Hebrew idioms that involve the word ‘hand’: ozlat yad – helplessness, and yad badavar – asking literally, do you feel you have a hand in this?

Einat Weitzman and Aziz Al-Turi’s work concerns Al-Araqeeb, a village north of Beer Sheva, unrecognized by the State of Israel. Aziz, with the help of four boys, constructed a home on the stage of Tmuna, from start to finish, in just half an hour. Barred by the court from hammering nails, Aziz watched the boys with a careful eye, offering guidance, while carrying on a conversation with the audience. At the time of this encounter, Aziz said that his village had been demolished 112 times. Each time their homes are destroyed, they rebuild, because they have no other home. Aziz said: “We have nowhere to go. We want to live, but with our culture. We want to live, but with our dignity.”

More photos from A-Genre on this link