Modern Times, an impressive collection of 50 masterpieces from the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) opens tonight at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art. Spanning a period of about 90 years, from the end of the 19th century to the mid- 20th century, the exhibit will be shown in the Sam and Ayala Zacks Pavilion from October 12, 2018 through February 2, 2019. Curator Jennifer Thompson, The Gloria and Jack Drosdick Curator of European Painting and Sculpture at PMA and Suzanne Landau, Director and Chief Curator of the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, offered insights into the exhibit in a preview tour for journalists.

“It truly has been a remarkable collaboration,” said Jennifer Thompson, and indeed, as the exhibit was originally designed to be shown only at the Palazzo Reale in Milan, where it recently closed on September 2, 2018, the swift and smooth transition reflects the close cooperation between the museums. Organized essentially in chronological order, in a spacious and serene setting within the Tel Aviv Museum, the exhibit offers visitors an opportunity to follow the development and different expressions of those artists now recognized as masters, who were considered rebels in their time.

Although the first painting in the exhibit is a Manet, the eye is almost immediately drawn to Mary Cassatt’s Woman with a Pearl Necklace in a Loge (1879). Illuminated by the lights of the Paris Opera, the woman (Cassatt’s sister Lydia) appears lit from within, a slight smile of anticipation dancing on her lips, as she sits in a pink evening gown with her back to a mirror, the grandeur of her vista – the opera and its colorful audience, seen as a reflection behind her.

This is where Suzanne Landau chose to begin the tour, because, as she said, “I think really she’s a hero, not only of the collection of the Philadelphia Museum but also of this exhibition.”

Mary Cassatt (1844 – 1926) is well known for her portraits of mothers and children, yet this exhibit not only serves as a reminder of her landmark role as a woman painter invited to exhibit with the Impressionists, but reveals the significance of her role in collecting and introducing others to the Impressionists. The Philadelphia Museum opened in 1876, and was, as Jennifer Thompson explained, “largely a museum of decorative arts, furniture and textiles and ceramics. It wasn’t until the 1920s that we became a fine arts museum and our painting collections started to form… largely with the Impressionists… Mary Cassatt, who was (of course from Philadelphia) a great painter who went to Paris to train and to live out her life and her professional career, but never lost her ties to Philadelphia encouraged collectors to buy Impressionist art.”

Cassatt trained at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts before coming to Paris. As a woman, she was not admitted to the École des Beaux Arts, and studied privately, as well as copying from paintings in the Louvre.

“Cassatt arrives in Paris in the middle of 1870s, submitting works to the salon and having uneven success and within a few years meets Camille Pisarro and Claude Monet, and in particular Edgar Degas, and they invite her to join their group,” Thompson explained, adding that the Impressionist exhibits were “an opportunity for the artists to show their work because they were rejected by the salon.” The painting Woman with a Pearl Necklace in a Loge was exhibited by Cassatt at the 4th Impressionist Exhibit in 1879, along with several other works. Thompson noted that the painting, currently set in an ornate gold frame, was probably originally in a flat, green frame (most of Cassatt’s original frames were lost over time). At that exhibit, Cassatt, who came from a wealthy family, purchased two paintings, one by Monet, and one by Degas, intended as a gift for her brother Alexander. The Degas, The Ballet Class, hangs next to the Cassatt, the proximity of the paintings reflecting the close working relationship between the two artists. Thompson recounted the painting’s quirky backstory: when Cassatt bought the painting, Degas asked to have it back so that he could work on some details. He then kept the painting for an entire year, altering almost every aspect of the painting. Eventually, the painting made its way to Cassatt’s brother in Philadelphia, where it introduced people to these different approaches to art.

In the center of the room is a bronze scupture by Auguste Rodin, and Thompson pointed out the Impressionist qualities of the sculpture in the attention to “light falling on the body, the muscles, something very temporal…[Impressionist art is] very much about a particular moment in time, Rodin quite effectively translates that into the human body.”

“The sitter, Sam White, grew up in Philadelphia,” said Thompson, “He’s the only Philadelphian who is known to have modeled for Rodin. White was a body builder. As a young man he attended Princeton University and then went on to study in Cambridge England. While he was in Europe he was introduced to Rodin who was very taken with White’s physique and asked White to model for him. This is something Rodin often did, he didn’t like to hire professional models, he liked people off the street, people who were untrained, because he felt they were more natural. You got a better sense of their personality and humanity… In gratitude for his work, Rodin presents him with this bronze. For White this sparked an interest in art.” Thompson noted that in the collection there are several pieces later acquired by White, who upon ending his bodybuilding career entered the family business of dental equipment, and with his wife the artist Vera McEntire, became a collector of art, ultimately bequeathing a collection of over 400 objects to the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

The exhibit as a whole is an exhilarating visual experience. Several of the works are also interesting in what they reveal about the artist’s process and development. The juxtaposition of a still life by Vincent Van Gogh, most probably painted before he visited Paris, and his bold, bright Portrait of Camille Roulin (1988), the postman’s wife, holding their baby, is striking.

Another glimpse into an artist’s process is afforded in Winter Landscape, a painting by Paul Cézanne, that in its unfinished state highlights Cézanne’s distinctive “Constructivist” brushstroke, and whose provenance makes an intriguing story. As Thompson recounted, Cezanne worked on this painting when visiting Monet in Giverny, around 1894. Monet hosted dinner parties, inviting his fellow artists, such as Cassatt, Sisley, and Renoir, for, as Thompson noted, by this time the Impressionists had “started to enjoy a more positive reputation, they’re feeling financially a little more secure, for Cézanne it’s still a moment of struggle because he’s one of the later artists to reach that level of fame and building his reputation. There’s reportedly a dinner at which Monet raised a glass to toast Cézanne and said how much we all admire you, we just want you to know that we have great faith in you. And Cézanne for some reason just took it badly and he thought that they were mocking him, because he didn’t believe that they had that much respect for him. So he departed in a huff. He departed the dinner party, he left his hotel, he abandoned this canvas at the hotel. He partly didn’t pay his hotel bills, so the hotel proprietress kept the painting. It was found in the attic about 20 years later by a pair of collectors, they were American painters who’d gone to Giverny to study with Monet.”

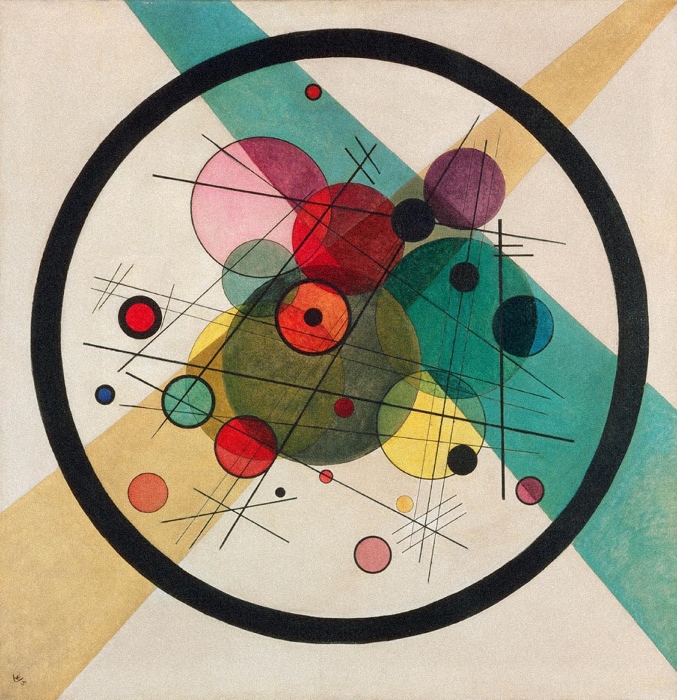

Modern Times features works by Pierre Bonnard, Constantin Brancusi, Georges Braque, Mary Cassatt, Paul Cézanne, Salvador Dalí, Edgar Degas, Paul Gauguin, van Gogh, Juan Gris, Vasily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Édouard Manet, Henri Matisse, Joan Miró, Claude Monet, Pablo Picasso, Camille Pissarro, and Auguste Renoir. The exhibit connects well with a visit to the Tel Aviv Museum’s galleries of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Art.

Additional information may be found on the Tel Aviv Museum of Art website.