Agnieszka Holland’s biographical feature Mr. Jones depicts the courage, perseverance and dedication to the truth of an unsung hero, Gareth Jones (1905 – 1935), a Welsh journalist who was one of the first to report on the Holodomor, the man-made famine of 1932 – 1933 in the Soviet Ukraine. Yet it is also an incisive commentary on the role of journalism in shaping world events, the responsibility inherent in that role, and the importance of journalistic ethics. For those who think that “fake news” is a modern invention, the film is quite an eye-opener.

Working as a Foreign Affairs Advisor to former Prime Minister David Lloyd George, Jones possessed the ability to confront the facts and understand where current decisions may lead. In reporting on his interview with Hitler, conducted in flight, he wrote: “If this aeroplane should crash then the whole history of Europe would be changed.” He was also possessed with a passion to investigate incongruities, and noting Stalin’s extensive expenditures, he resolved to go to Moscow to find out where the money was coming from. His experiences in the Soviet Union, the harsh reality he found there, and the subsequent controversy over the publication of those findings, form the essence of Holland’s film.

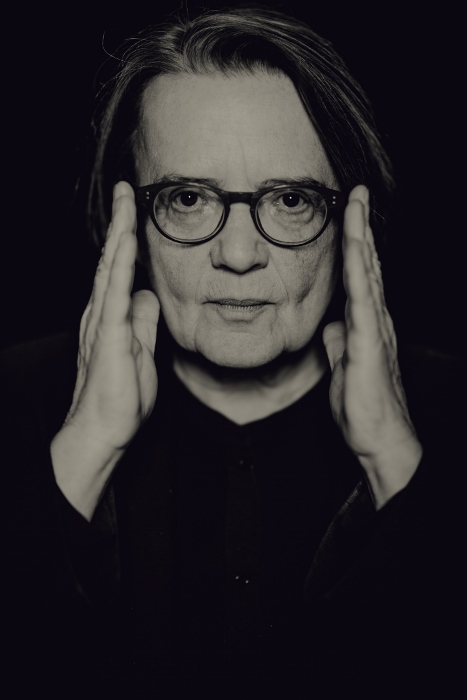

Following the film’s screening at the Haifa International Film Festival, Agnieszka Holland discussed the film and her work in a masterclass moderated by film critic David D’Arcy. Holland said that she became acquainted with Gareth Jone’s story in Timothy D. Snyder’s book Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin, published in 2010. Although Jones’ story is not generally well known, Holland commented:

“He was better known in the Ukraine, after the long silence about the Holodomor, the silence which took practically 60 years. In the new country of the Ukraine, the independent state of Ukraine, of course they started to speak of it, and it became a very traumatic memory of their own past, because the memory of this famine was practically in every family, but the people had not been talking about it, first because it was forbidden and second because it was too traumatic, and too humiliating. But when I was shooting in the Ukraine, the scenes in the villages were shot in the Ukraine, in the places which looked exactly like 70 years ago. The villages have been mostly abandoned but there were several old women living there, and all those women remembered the famine as girls. Some of them talked to us about it, and two of them talked about it for the first time in their lives.”

Holland discussed the role of media in influencing opinions and events:

“I’ve been thinking for a long time that the filmmakers and the television people forgot very easily Stalin’s communist crimes and that those crimes stayed untold, and the victims of these crimes have been speechless, have been silenced, and I think that it influences somehow the current political and moral situation, in Europe at least…I wanted to raise one question. I think is very relevant in our days the question about journalism – what the media means in a divided, polarized world and ideologically rooted in one or another bubble or camp, the objectivity of the media is necessary. What journalism means, what is its responsibility, what is the meaning of true information, regardless of what it means for my camp. What does fake news mean? That for me was a very important question.”

David D’Arcy asked Holland to comment on the experience of growing up reading Polish newspapers, on the assumption that she was extremely mistrustful of that media. Holland responded:

“Well, communist media was like a wall. Somehow the main Soviet party newspaper the name was Pravda, it means truth. It was the opposite of the truth, it was like in Orwell’s 1984 the truth was called lies, the lies truth, war was called peace and so on. So, because it was as simple as that, somehow it was quite easy to realize that it was pure propaganda and to read it backward. Most of the people didn’t believe in official party propaganda and the journalists. My parents were journalists and they tried to pass as much of the truth as possible. They were writing about foreign politics, the education in the countryside. And people had the access, which was quite difficult, to some press and some books and also Radio Free Europe have been broadcasting the news practically all day and night and the authority have been blocking it, making some noises over that, but with good radio you can hear at least half of those. And it meant, journalists meant something…The people had some confidence that it could change their life if they know the truth. And today we are in much worse situation because you have so many truths and so much fake news and so many bubbles, so you don’t have something which makes democracy strong with the public media in Europe. For example, you don’t have the platform and the people of different political opinions can gather together and discuss the facts, and they trust that the facts were not distorted. So, you don’t have it anymore. In any country practically.

It’s why the fake news now are so efficient and why the propaganda can be so dangerous. It’s just the question of money and some intelligence, which for example, Vladimir Putin has very strongly, and you are able to completely change the political situation in one or another country. You know the story of Trump’s elections and influence of Russians in that. You know the story of Brexit, is pretty well documented how it was placed based on fake news. Of course the propaganda always uses some real fears and some real problems but after, it can do whatever they want. But all the propaganda is not enough to build up the danger of the totalitarian regime. I think you need three factors: one is the corruption of the media, and the opportunism of politicians, and the third one is the indifference of the general audience. When we have the three of them anything is possible.”

Asked by David D’Arcy, what she would want the audience to take from the film, Holland replied:

“Not planning like to change the world or something. When I feel that some questions or some experience is important to share, I’m pushed to do the film about it, especially if I have the script which helps me…fictional cinema, by building up some kind of empathy, it can open people’s eyes to some extent. Of course, not everybody, but some small amount of people. What concerns for example the Holocaust, I don’t think that it will be so well known in the US or even Germany if not for some films, even some kitschy films or TV series which are touching people’s hearts. Cinema can play some role in raising some questions and waking up the moral conscience or emotional connection to the work of others.”