The Vakhtangov Theatre production of Our Class, by Tadeusz Słobodzianek, is a very striking, thought-provoking, and moving play. Director Natalya Kovaleva has created a very vivid, fast-paced and physical interpretation of the text, with creative use of movement, music, and props to convey complex situations and consider issues of moral and emotional ambiguity, with excellent performances by the ensemble cast. The play was performed at Habima Theatre in Tel Aviv as part of the M.ART Festival of Russian Culture in Israel.

Słobodzianek’s play is based on a historical event: the massacre of Jews in Jedwabne, Poland on July 10, 1941, described in the book Neighbors: The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne, Poland, by Jan Tomasz Gross (Polish edition, 2000; English edition, 2001). This horrific event is even more difficult to comprehend, as the Jews of Jedwabne were tortured and murdered not by the Germans, but by their fellow Poles.

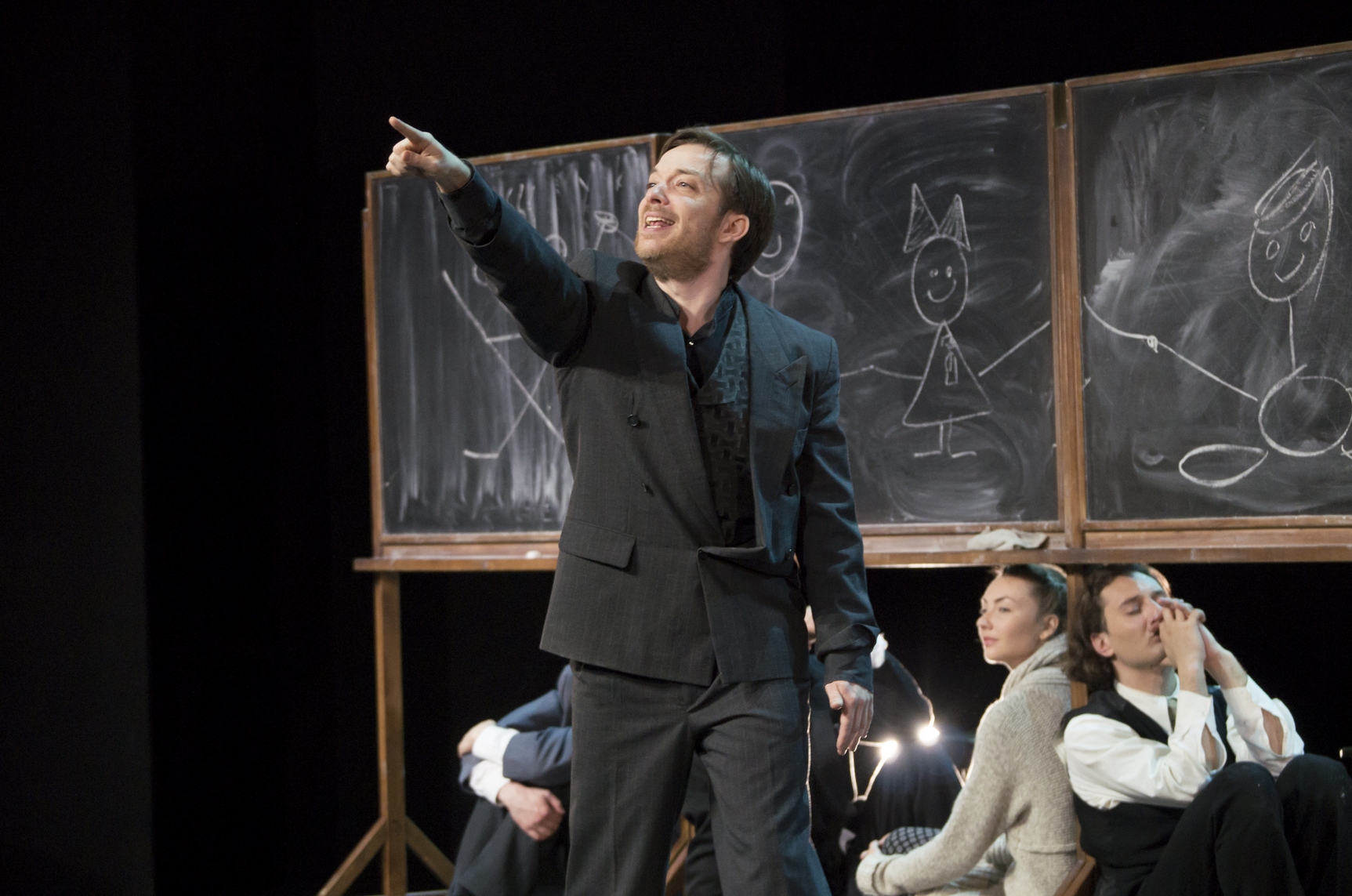

The play explores these issues through the intertwined narratives and fates of ten classmates, the five boys and five girls, Jews and Poles, who comprise Our Class. Divided into 14 Lessons, scenes in the lives of these ten classmates play out over the years, from their shared school days, through the harrowing historical events of Soviet occupation, WWII, and the aftermath of the war. The bare facts of their destinies are known: some will not survive. This is reflected in the deceptively simple set design by Alexander Borovsky, as ten individual blackboards mounted on stands with wheels, represent each student, with a chalk drawing – an outline of a head – accompanied by date of birth and date of death. Small wooden stools that will be put to myriad uses rest under the blackboards. Opening with one actor seated at a large desk, such as might be used by a teacher, the atmosphere of a typical classroom is established. Instantly, the rest of the cast emerges and bursts into song, evoking the folk songs and games of the schoolyard. In this moment, they are a blur of activity, reflecting the exuberance of youth; if not for their names, one would not be able to distinguish between Jew and Pole.

Yet by Lesson Two the differences emerge. Risiek reveals his love for Dora by making her a Valentine. He is quite aware of her “Jewishness,” it is problematic for him, yet he is still drawn to her. There is a tension between his feelings as an individual, and his sense of identity as a Christian Pole. When the others find out, they all make a huge commotion, teasing the two, surrounding them, calling out “Jewish” phrases – “menorah”, “mohel” – and laughing uproariously. It’s all in fun – or is it? What is the boundary between playful teasing and bullying?

Risiek is specifically targeted for having a crush on a Jewish girl, and made to suffer for it. Anti-Semitism is already in the classroom. The teasing turns rough, and he ends up in tears, saying “they laughed at me.” The scenes play out in a duality, as the characters live the action, yet also comment on the events. Even the characters who die in the course of the play, remain onstage, usually on the sidelines, yet still coming in to comment and participate. Towards the end of the scene Dora says, in a tone of regret, “What could I do?” This question that is not a question, implying that there was nothing she could have done, and had no choice in the matter, reflects a recurring motif in the play: what is the responsibility of the individual? Can an individual affect the course of events? Does an individual have the agency to make choices in every situation?

Running approximately three hours (including intermission), Our Class is a very long play, and it demands much from its audience. Yet the length is necessary in order to convey the nuances and complexity of the moral issues and emotional terrain it explores. Yet despite the harsh events it depicts, the experience of viewing the play is not bleak. A beautiful musical motif recurs throughout the play, as do different renditions of the folk song Tumbalalaika, which changes its tune from playful to nightmarish, according to the situation it reflects. Movement and dance have an impact far beyond words, from a stand-out jazzy number to the tune of Let My People Go that accompanies Abram’s description of his arrival in that promised land – America, to the ominous rhythmic approach of Zygmunt to Vladek, as he dances towards him, offering his help in a manner most threatening.

As the lives of these ten unfold, the focus is on the changing circumstances with which they are confronted, and the choices they make. They speak often of loyalty, and the sense of belonging they feel as classmates, even saying that a classmate is like family – yet their lives are replete with compromises, secrets, lies, and betrayals. Acts of courage and compassion, as when Zocha hides Menahem in her home, thus saving his life, are complicated by actions motivated by helplessness and fear: when Zocha sees Dora, who is Menahem’s wife, on her knees in the city square, commanded to scrape out weeds with a spoon, she tells her that she cannot help her. “What could I do?”

Our Class

By Tadeusz Słobodzianek

Director: Natalya Kovaleva; Set designer: Aleksandr Borovsky; Composer: Klavdiya Tarabrina; Main Musical theme written and performed by Daria Scherbakova; Choreographer: Irina Filippova; Cast: Zocha – Polina Kuzminskaya; Rachelka – Kseniya Kubasova; Dora – Daria Scherbakova; Jakub Katz – Eldar Tramov; Rysiek – Yryi Polyak; Menahem – Vladimir Shulyev; Zygmunt – Vladimir Logvinov; Heniek – Aleksey Gimmelyreyh; Wladek – Pavel Popov/Denis Samoylov; Abram – Maksim Sevrinovsky