The interpretation of any story or play depends upon the perspective of the person receiving that story, the viewer, as much as its creator. In the Cameri Theatre production The Tank, directed by Irad Rubinstain, there is a Rashomon-like telling of five different characters. Each man has his own memories of the same historical event – the Syrian tank stopped at the gates of Kibbutz Degania Alef in 1948; each one believes that he is the one who stopped the tank, changing the course of the war. The play, written by Yoav Shutan-Goshen and Irad Rubinstain is based on the book The Tank, by Assaf Inbari. Inbari’s book, in turn, is based on his research of the event. The five men depicted in the play – Baruch Bar Lev, Shlomo Anschel, David Zarchia, Shalom Hochbaum and Itzhak Eshet – share the names of the men who were involved in the historical event, but the play does not claim to be a representation of true events, on the contrary, it declares itself as fiction. As such, it takes its place in the making of Israeli myth, and what one makes of this myth, is up to the viewer. Is this a narrative of heroism? If so, who is the hero? Is it the person who stopped the tank, whoever he may be, or perhaps there’s more than one hero, or more than one way to understand heroism?

Each of the play’s five parts follows one man, revealing the way the story has accompanied him over the years, impacting the trajectory of his life. David Zarchia (Yoav Levi) is eager to pass on a tradition of heroism to his son Shabi (Dolev Ochana), a sensitive youth who excels in chess. He’s proud of Shabi, but wants him to learn to hit back, to stand up for himself despite his fear, and repeats the story of the Syrian tank as a guide for life. Time passes and the scene shifts to 1973 and the Yom Kippur War. Shabi is now an officer with a tank to command. Dolev Ochana’s demeanor and body language convey Shabi’s transformation from a gangly youth, slightly insecure and easily impressed, to a confident, capable young man. Yoav Levi delivers a moving performance as the father whose adulation of heroism is challenged by his encounter with the reality of war.

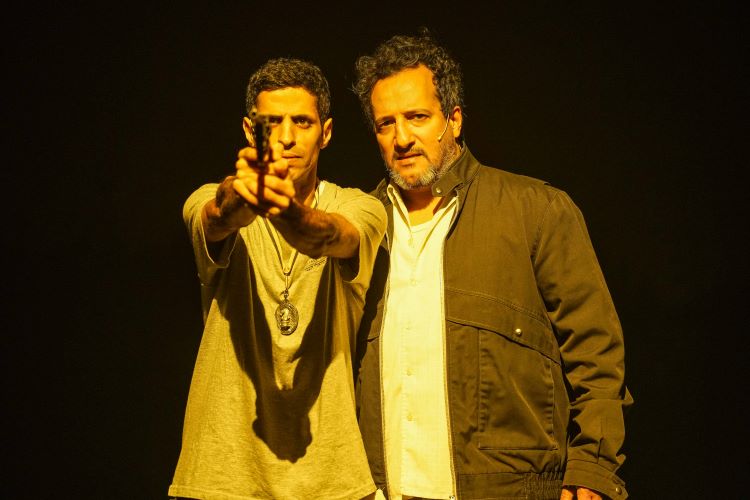

The visual concept for the play is evocative and powerful. The set and costumes, by Eran Atzmon and Modi Mednik respectively, share a unifying element for all five stories. The floor of the stage is a muddy, rocky, ground, with the mud reaching part-way up the walls, and all the costumes have mud on their shoes and lower part of the trousers, stockings, or legs. This image of mud, that covers everything and cannot be cleaned off, raises so many associations and possibilities for interpretation. The land, the ground of Israel is an integral part of Israeli history, politics and myth. All the characters in the play are of this land, this muddy earth, and imprinted with it; they are implicated in its story, they cannot evade it.

Each chapter, centered on a different individual, is conveyed in a different manner and style. The experiences of Baruch Bar-Lev (Nadav Assulin) include a song-and-dance routine between Borke and Idi Amin, and reflects the ability of the political party in power to manipulate events and their documentation. For some of these men, like Eshet (Dudu Niv), the story of the tank was an anchor for their self-esteem, when all else goes wrong, they can cling to the memory of this success. When the myth meets the reality of war, as Eshet volunteers for reserve duty during the Yom Kippur war, a reassessment must be made, and a task that appears meaningless, shifting duffel bags from one place to another, suddenly takes on grave meaning. Anshel’s (Simcha Barbiro) story is told entirely as musical theatre. Anshel is a driver with a bus load of war veterans with disabilities, each singing out his story in a scene that challenges the popular Israeli assurance of “yehiye beseder” (it will be OK). Shalom Hochbaum’s (Micha Selektar) situation is very different from the others. Siegfried, a Holocaust survivor, arrives at Kibbutz Degania to begin a new life with a new name. Of the five men, he is the only one who wants to forget the past. Yet when the kibbutz declares him a hero, he is compelled to tell his story over and over again. Selektar delivers a moving performance of a man desperately trying to overcome the trauma of his past, and fulfill his responsibility to the place where he found refuge.

The Tank is not structured as a mystery. One follows the stories of these men, not to discover the “real” hero, but to become acquainted with their characters, the harsh reality of war, and the impact it has on their lives. The play ends in what might be a surprising way, yet for this viewer, felt that it brought a welcome sense of closure in its refusal of closure.

The Tank

By Yoav Shutan-Goshen and Irad Rubinstain

Israeli myth adapted from Assaf Inbari’s book

Director: Irad Rubinstain; Set: Eran Atzmon; Costumes: Moni Mednik; Music: Roy Yarkoni; Lighting: Avi Yona Bueno; Movement: Amit Zamir; Cast: Yoav Levi (Zarchia), Dolev Ochana (Shabi), Micha Selektar (Shalom Hochbaum), Simcha Barbiro (Anshel), Tal Weiss (Ami), Moran Arbiv-Gans (Aliza), Gal Seri (Yehudit), Dudu Niv (Eshet), Nadav Assulin (Borka), Sean (Chonsella) Mongoza (Idi Amin)*all cast members portray several characters in the play, I’ve only noted their primary or first character