“I am not responsible for what you see on the screen. Not a bit.”

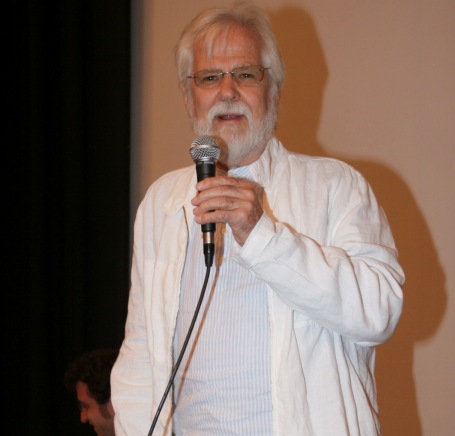

Jan Harlan

In a career in film spanning 40 years, the list of Jan Harlan’s credits in fiction films is a rather short one. Executive producer of five films; assistant to the producer on another. That may not sound particularly impressive…but look at the titles. ‘A Clockwork Orange’, ‘Barry Lyndon’, ‘The Shining’, ‘Eyes Wide Shut’, and ‘A.I.- Artificial Intelligence’.

Jan Harlan’s career in film is inextricably linked to a single, towering figure- that of Stanley Kubrick. While filming ‘Paths of Glory’ in 1957, Kubrick cast Harlan’s sister, Christiane, to be in the unforgettable final scene of that film. The two were married shortly after that. A decade or so later, Kubrick asked his brother-in-law to join the small group of collaborators with whom he made films, and ever since then, Jan Harlan has been known to film-lovers as one of the few people in the inner circle of one of the greatest and most enigmatic film directors in history.

According to Harlan, his main artistic contribution to the films he worked on was suggesting music. And it was music that was at the core of his 90 minute lecture, given at an auditorium at the Tel-Aviv Cinematheque that was packed with burgeoning filmmakers. Harlan was a special guest of the Tel Aviv Student Film Festival, and decided to talk about a few of the cinematic principles that he regularly teaches in film schools across Europe, and particularly the use and value of music in film.

As a judge at student film festivals, Harlan bemoaned the darkness that is pervasive in many of the films he sees, and the coldness of the outlook of the young directors. One of the ways to inject more life into them is through music. Harlan gave ample examples, from Mendelssohn to the score to ‘Titanic’, of the structure of melody and how a good, malleable melody is the most effective base for a film score.

Harlan also spoke about the art of visual story-telling, using a number of film clips from ‘The English Patient’, ‘Spirit of the Beehive’ and the short film ‘Lost Paradise’, which was directed by Israeli directors Mihal Brezis and Oded Binnun, and found time to expound on his theory about the great importance of the opening 3 minutes of a film. But he always came back to the importance of music in film.

After the lecture, I sat down with Harlan at the Cinematheque Café for a brief conversation about Stanley Kubrick and music for film.

Harlan, in fact, inspired one of the most iconic uses of music in film history- “I recommended ‘Zarathustra’ to him for ‘2001’. I don’t take credit for it- I just knew it, and he didn’t.”

The use of ‘Thus Spoke Zarathustra’ and ‘The Blue Danube Waltz’, as well as music by Ligetti and Penderezcki, was not Kubrick’s original plan for the music for the film. Kubrick hired Alex North, with whom he worked to great success on ‘Spartacus’, to write a score for 2001. The score was recorded and has been released on CD, but Kubrick decided to go another route, and continued to compile the music for his films almost entirely from pre-existing works.

“The story is very simple- he had Alex North, Alex North wrote a very decent score, nothing wrong with it, but it didn’t totally satisfy Kubrick- typical of him.”

Didn’t have the same mythic connotations?

“No. And when he heard Strauss- And Thus Spoke Zarathustra- wow! That’s what he really liked.

And of course it’s also great music that comes to an end. Don’t have to fade it out.”

It has a definite shape that is set.

“Wonderful shape. It’s a fanfare. He was both clearly aware of his abilities, but also very respectful of other artists, and wouldn’t want to cut the music. He would edit the film to the music, not the other way around. Very respectful of good work.”

Music, Harlan says, “Was my only artistic contribution to the films. Of course we discussed the film, but basically my job was to negotiate, to make deals, to make contracts.”

Harlan’s training, in fact, had nothing to do with filmmaking. “My training, in New York and in Zurich and in Vienna was business planning”. The professional relationship only came when Kubrick needed help organizing a difficult shoot in Europe. Until the late 60’s, Harlan says “I had nothing to do with him- I mean, I saw him regularly because he was married to my sister, so we played with the children and talked about music ect..But I hadn’t the slightest interest in working with him. Nice guy, interesting, liked music, but I was deeply involved in my career. And then I went back to Zurich, and only in 1969 he asked me to join him for a year to go do ‘Napoleon’.”

‘Napoleon’ never came together, and became one of Kubrick’s legendary aborted projects. On Kubrick’s next film, ‘A Clockwork Orange’, Harlan got his first screen credit “as an assistant. After ‘Napelon’ didn’t happen, I stayed. I loved England, I loved him- one thing was leading to the other. But I was basically dealing with finances and planning, legal stuff. I bought rights to books.”

Harlan became part of the very tight-knit community surrounding Kubrick, who for the remainder of his career made his films in and around England. Kubrick’s lack of public appearances and travel to the US caused a somewhat extreme portrait to be painted of him in the American press- that of an obsessive hermit, a cold and distant artist and human being. While quite extreme, this idea of Kubrick gained momentum as his films became less frequent, more controlled, and his main characters seemed more and more like blank slates, as opposed to vital participants in their own existence.

Harlan, on the other hand, is convivial and vivacious, expressing pragmatism, yes, but also great romanticism. When I asked him about the seemingly clashing temperaments, Harlan responds “Maybe that’s why we got along so well” and that talk of Kubrick’s coldness as an artist were not reflective of him as a human being. He “was surrounded by family and animals. He was a very warm man”.

Speaking of opposites, one of the most curious and fascinating creative partnerships Kubrick had, was with a filmmaker with a diametrically opposite reputation- Steven Spielberg. “He loved Spielberg, because he was so totally different from him. Great artists always love totally different, equally great, artists.”

The film that resulted, ‘A.I. Artificial Intelligence’, is the last film (to date) the bears Stanley Kubrick’s name. It was highly anticipated when it came out in 2001, but its reception was extremely mixed. Some found it to be terrible. Most found it to be kind of interesting but ultimately boring, with a schmaltzy ending that they interpreted as a happy ending forced in by Spielberg. The film did find a strong group of supporters, however, and its reputation has slowly gained in stature since its release.

To the accusation that Spielberg messed with the implications of Kubrick’s concepts, Harlan responds that “Spielberg was very faithful to Kubrick’s concept. It’s basically a dark film. Very dark film. I mean- we are gone! Humanity has disappeared. Never mind why- it’s taken as fate accompli, we have no chance to survive the way we behave. It’s our machines that survive as the only remnant of our ingenuity.”

“We don’t know how much longer humanity exists after little David gets trapped- 200 years, 500 years…suddenly it goes forward 2,000 years. Now comes a very important scene that many people don’t understand. When the robots find little David, like an archeological find, they all touch each other, and at the same time get the information, transmitted from one to the other. So there’s no hierarchy, no envy. It’s envy and hierarchy that finishes us all. It was very much Kubrick’s thesis.”

I asked Harlan about the music for the film, which was composed by John Williams, which makes ‘A.I’. the first Kubrick project since ‘Spartacus’ to have a full score by a single film composer.

“I can tell you exactly, because it was already decided- we had decided to use a Strauss waltz in the film. The waltz from the second act of ‘Der Rosenkavalier’. We had a scene where David learns to play it on the piano. Spielberg had to adapt the project to his own imagination. He loves Williams- terrific. Kubrick wouldn’t have used Williams, but that doesn’t mean it’s better or worse.”

Although inextricably linked to Stanley Kubrick, the Harlan family has another known filmmaker in its midst. Veit Harlan, the uncle of Jan Harlan and Christiane Kubrick, was one of the most famous filmmakers of the Nazi era, second only to Leni Riefenshtal in his stature in the Nazi film industry. Last year, German documentarian Felix Moeller made ‘Harlan – In The Shadow of Jew Süss’, a documentary about Veit Harlan and his most infamous propaganda film. Moeller interviewed many of Harlan’s relatives, including Jan Harlan and Christiane Kubrick. I asked Harlan about his feelings about the film.

“Well, I contributed to it, I’m in it. I think it’s a story that should be told, as often as you can. I think the guy did a very good job. He let others say what they feel about it, instead of coming up with some theories. I don’t mind at all. I think the topic should be repeated again and again. It’s a good topic to be mentioned and repeated. The Nazis…it is so unbelievable. In fact, it is not understandable. When the director asked me to be in it, I said ‘absolutely’. So did my sister, and the whole family, they all spoke. Nothing wrong with it- it’s not our dirty laundry. Sometimes I’m asked to give an interview about Veit Harlan, and I say I know much more about Stanley Kubrick.”

SHLOMO PORATH