There is so much to write about Avigdor Arikha, artist, art theorist and curator who passed away in Paris in April of this year. Firstly, his life story is full of interest. Born in Romania in 1929, he was raised in a cultured home until the age of eleven when he and his family were deported to a concentration camp. There, already a talented draughtsman, he made drawings of what he saw and experienced. The scraps of paper he drew on survived. Eventually rescued through the intervention of the International Red Cross, he and his sister, now orphans, were brought to Palestine in 1944 under the auspices of Youth Aliya to live at Kibbutz Ma’aleh Hahamisha. Studies at Bezalel followed, and in 1949 he was awarded a scholarship for further studies in Paris, the city where he would live from 1954 onwards, together with his wife Anne Atik, the American poet and writer.

And then there is much that could be written about Arikha’s artistic journey that garnered him international fame and respect. Over the years his style underwent changes; at first he was a figurative painter, turning to abstraction in the early 1950s. Later he would stop painting completely, confining himself to drawing and printmaking for seven years. His return to color and to painting in 1973 heralded the production of an extraordinary body of work: portraits and self-portraits, landscapes of Israel and still life renderings of everyday objects. It was Arikha’s custom to paint directly from his subject in natural daylight with no preliminary sketches, finishing whatever he was working on – whether a painting, drawing or print – in the space of a day.

Paying homage to the memory of Arikha is a two-part exhibition showing at the Tel Aviv Museum, curated by Mordechai Omer, a specialist in Arikha’s work. The first part comprises a 19-piece selection of remarkable self-portraits dating between 1948 and 2001; the second, the endearing illustrations that Arikha completed in the 1950s for A Stray Dog, a story taken from Only Yesterday, an epic novel by Nobel Laureate S. Y. Agnon, first published in 1945.

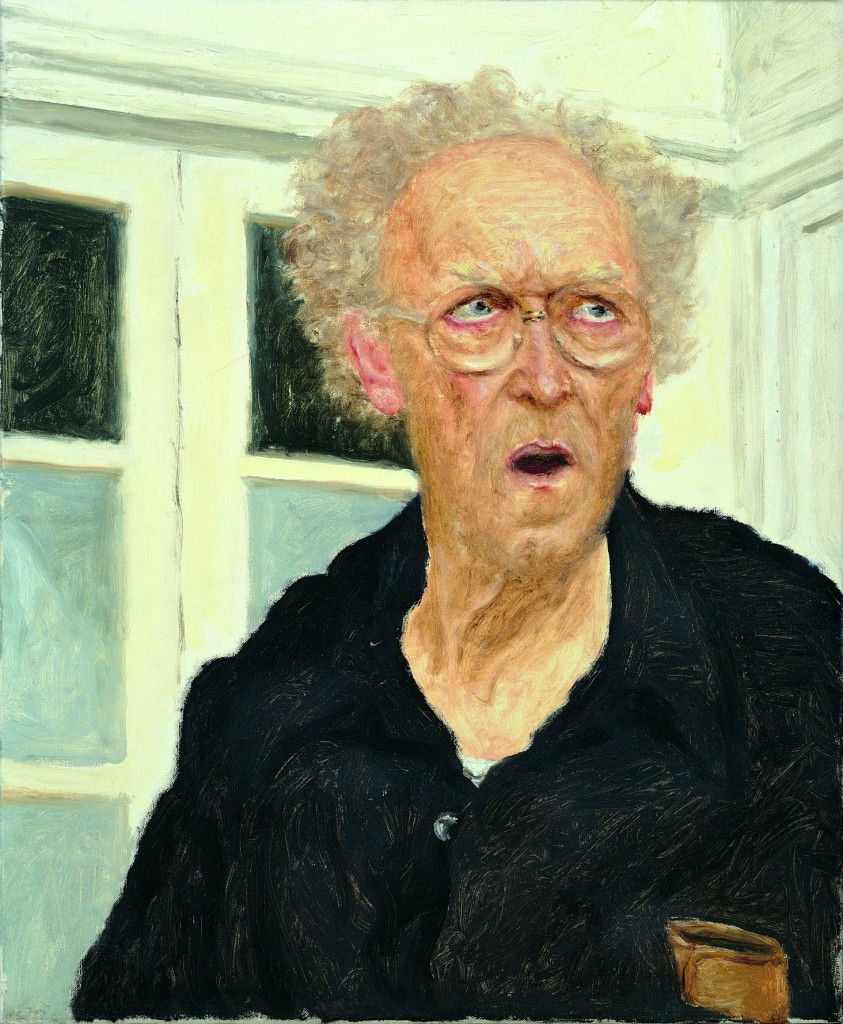

As his self-portraits attest, Arikha was a master of this genre. Many artists are able to capture their own likenesses, but very few possess the skills to express within their paintings the intensity and emotion involved in the creative process. Arikha not only bared his emotions to the viewer, but also, quite often, his body as well; as in Self-Portrait from the Back in Underpants, (where the artist used two mirrors to correct the image reversal.) This detailed painting of his skin traces a scar in the area of the spine, remnant of the serious wound he sustained as a soldier fighting in the War of Independence.

Self-Portrait in the Studio is representative of a number of self-portraits in which Arikha depicts himself in a state of distress, mouth gaping open. Omer relates that Arikha first saw, and was deeply affected by, the image of a crying mouth in a 1965 exhibition at the Louvre where paintings by the Italian baroque painter Caravaggio were on display, his depiction of a screaming Medusa being an especially memorable example of this imagery.

.

In all his self-portraits, Arikha has frozen some momentary gesture or expression on his face: there one moment, gone the next. In doing so he raises the question of what is reality all about and can an artist truly pin it down. Art critic Robert Hughes has related this feature so fundamental to Arikha’s art to the fact that this artist is “charged with curiosity about the world out there and motivated by an excruciating awareness of how provisional seeing is, how mutable, how rarely final in its deductions.”

Arikha’s Stray Dog illustrations comprise five woodcuts and 16 drawings produced in the 1950s employing ink and pen or a fine brush. ‘Introducing’ this series are some pencil portraits of Agnon, and also several of Dr. Moshe Spitzer who was instrumental in bringing Agnon and Arikha together, and whose publishing house Tarshish in 1960 brought out the book that featured Agnon’s story about the dog together with Arikha’s illustrations.

These prints and drawings present a unique opportunity to illuminate another aspect of the skills of an artist who Hughes considered to be “the best draughtsman of his generation, perhaps the best to have emerged in Europe since the death (in 1960) of Giacometti.”

In these illustrations Arikha remains faithful to Agnon’s descriptions in a story whose ‘hero’ is Isaac Kumer, a disenchanted immigrant of the Second Aliyah. In the course of this young man’s wanderings, he finds a stray animal and paints the words Crazy Dog on his back. (The dog plays an allegorical role in this story which is about destiny and fate, hope and disillusionment.)

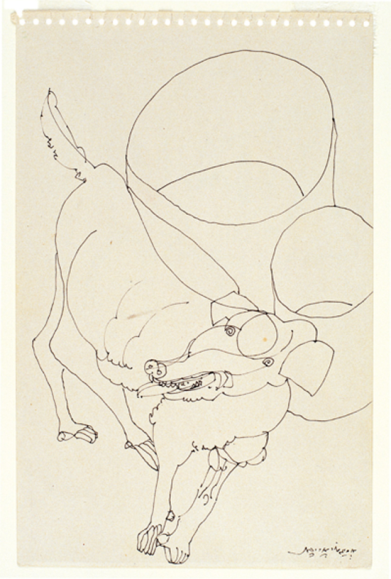

This animal makes its first appearance in a pen and ink drawing by Arikha executed in his characteristic style of fine continuous lines skimming his papers. According to Agnon’s description, he gives the dog cropped ears and a mangy tail, but instead of painting words on the animal’s back, Arikha marks his forehead with a circle that Omer in the exhibition’s catalog text aptly describes as the Mark of Cain.

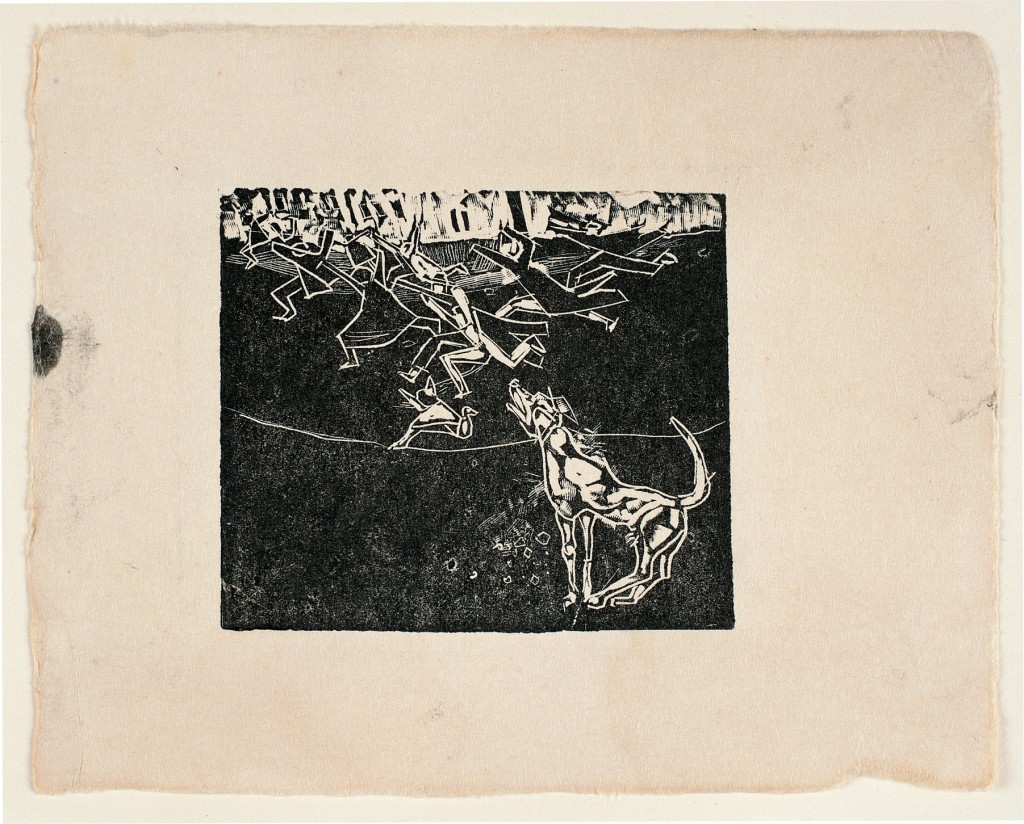

A trio of woodcuts relates to the next part of the story in which the dog standing in a Mea Shearim street creates panic, adults and children running away. Arikha renders these figures in flight as stylized geometric shapes. People start to stone the dog who of course has no idea why he is being treated so brutally. Eventually he goes mad and bites Isaac Kumer.

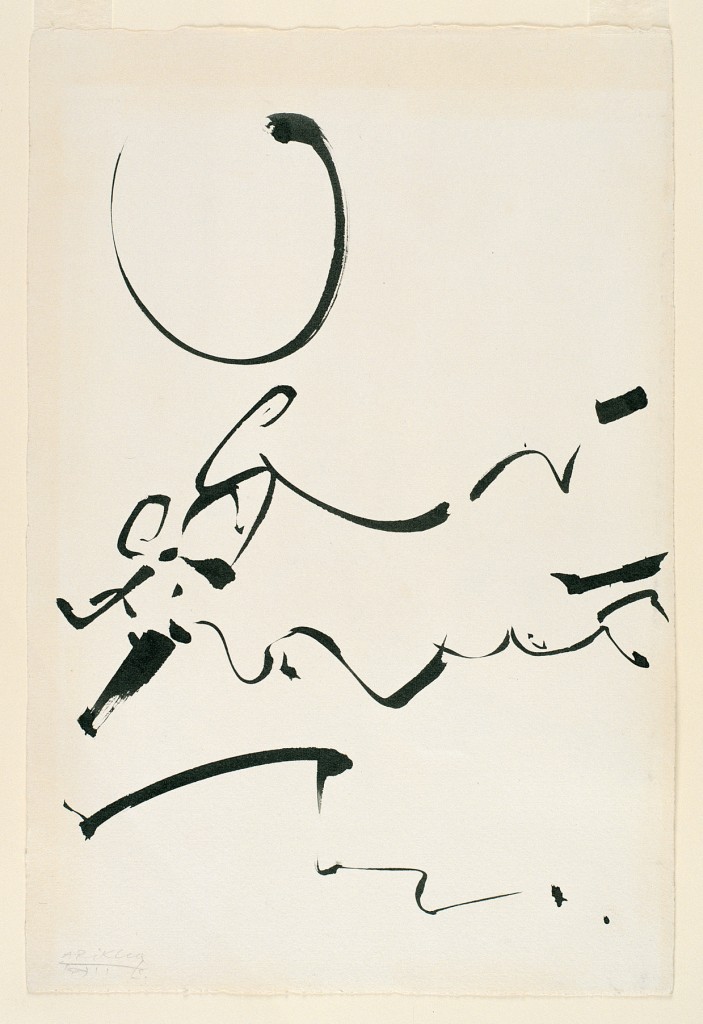

The last part of this story is rendered in brush and ink drawings that are abstract in style, but of great beauty; their economy of touch and calligraphic presence recalling Chinese brush paintings. It is fascinating to see that Arikha was able to make these reductive drawings so highly expressive, evoking in a few curves, lines and black patches, the dog’s rippling body as it charges aggressively forward.

ANGELA LEVINE