Malenki Theatre’s new home is a black box with wings – and in it, they soar. Job, The Story of A Simple Man, adapted from the novel by Joseph Roth by Roy Chen and Igor Berezin, and directed by Igor Berezin, premiered in the company’s new venue – Tel Aviv’s Gay Center in Gan Meir, this past weekend.

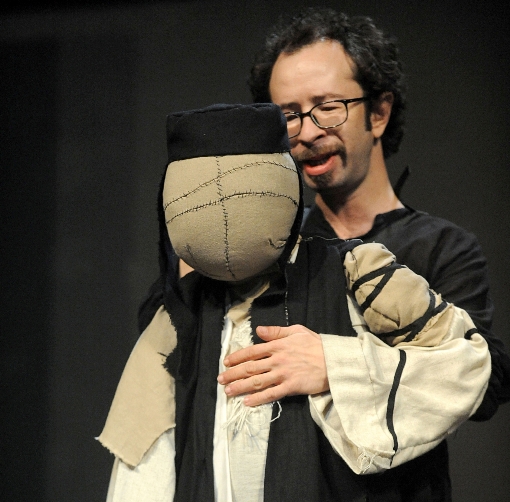

Malenki’s Job reaches far beyond the reworking of prose into dialogue; the novel has been brilliantly re-imagined as theatre. Embodying Rimbaud’s statement “Je est un autre” the actors work with large-scale fabric puppets desigend by Polina Adamov and made by Oxana Yanovitsky and Leonid Elisov. The puppets are strapped onto the actor’s torso, arms slipped through the sleeves of the garment with the actor’s hands emerging from the sleeves and feet revealed at the hem, they merge and move together, and yet remain separate.

The puppets are faceless; the entire first act takes place in the simple austerity of a black box. There are no illusions or pretense of realism – Job is a celebration of art.

Roth’s novel begins in the realm of myth – “Many years ago” and tells the story of Mendel Singer, a teacher of children “without notable success” in Zuchnow, Russia, with the Biblical story of Job as its frame of reference. Self-reflective at every turn, the play begins with two men holding up a large puppet, flanked by two seated actors: Dima Ross and Esti Nissim. Ross begins to recite the familiar Biblical text “There was a man in the land of Uz named Job,” setting up a multi-layered dialogue within the play from the very first moment. Soon he will literally step into a character as he straps on the puppet with its black skullcap, long black ear locks, black leather strap wound around the arm and white fringed tzitzit – literally embracing his identity as Mendel Singer.

Like a master puppeteer, Berezin makes a deliberate choice to begin with an act of connection – to the Biblical text, and the physical connection of the actor to the puppet, that is also an act of displacement. Just as the play refers to something outside itself, a prior text – the novel, we are reminded that the novel refers to a prior text, the book, the Bible. Refusing illusion, the casual strapping on of the puppets, recalling the everyday routines of getting dressed in the morning, tying on teffilin, implies that as an audience we are never allowed to forget that Dima Ross is and is not Mendel Singer – and Mendel Singer, is and is not Mendel Singer.

Who is Mendel Singer – a puppet, a character in a play, a man, a Jew? Actor and puppet are distinct in their appearance: Ross is dressed in functional, contemporary black shirt and pants; the puppet wears the traditional garments of a religious Jew. This daring and creative construction sets up a symbolic relation to Jewish identity, allows us to see it, and see the actors relating to it as a physical presence onstage. In situating Mendel Singer as a fictional character, a puppet – the audience is free to see beyond the familiar myths and stereotypes, into the absurdity and complexity of his humanity and the strange myth of identity itself.

Malenki Theatre has put on a terrific show that speaks in a multiplicity of voices and languages: verbal, visual, physical, musical. Hebrew, Russian, English, Biblical texts, Yiddish lullabies and an old song (Glory, glory, what a hell of a way to die) sung by American paratroopers to the tune of Battle Hymn of the Republic – their presence creates a many-layered discourse of associations. The first scenes establish a self-deprecating comic rhythm to the play, in the familiar scenes of Jewish life: the poor yet devout Mendel (Dima Ross), his pragmatic, complaining wife Dvora (Esti Nissim), and the children who tumble into their lives one after another: Jonah (Vadim Halif), Shemaryahu (Yonatan Bar Or), Miriam (Anat Gat) and Menuchem (Yefim Rinenberg).

The poetic quality of Roth’s novel is captured in movement, visuals and the use of text as sound. The comic, musical incantation of Dvora’s litany of complaints: “Why are the carrots small, why are there no eggs, why are the potatoes frozen,” is chanted over a tin washtub, jamming with Mendel’s recitation to his students. The rituals of daily life and the traditional elements of the Jewish story are performed with vaudeville-like physical humor within the frame of a contemporary sensibility. Yet Berezin’s strength as a director is most evident in moments when he takes the characters and the audience beyond words, penetrating the vast, hidden places of the soul: awakening in the night, Dvora tears through the fabric of her character, the comic density of the Jewish peasant woman, with a sense of wonder, discovery and loss, alone by the side of her sleeping husband Mendel.

Questions of identity, loneliness and desire dance through every beautifully choreographed moment in the life of Mendel Singer, his wife Dvora and their children. These puppets yearn to live, to be noticed, chosen, and loved. Within the familiar story of the European Jew – struggling with poverty, living in constant uncertainty in fear of the authorities, the tensions between Jewish and secular life, the security and suffocation of family life, the attraction of America and the permanent sense of exile – each character is and transcends the stereotype. Accompanying the physical doubling of identity between actor and puppet is the sense that there are always at least two different ways to look at anything, and meaning is transformed by context.

If at first the actors are as one with the puppets, merging and moving in unison, the slight distance between the face of the actor and the cloth face of the puppet becomes a crucial element in the play. At first comic, as when Jonah, the oldest son, discovers vodka and the actor looks on in slightly detached amusement as the puppet head flops into drunken oblivion. When two sons are drafted into the Russian army, the resourceful Dvora ignores Mendel’s injunction to surrender to God’s will, and turns to “people who can help,” but it turns out that her carefully hoarded money is only enough to buy out one son. Her pained announcement is broken by Jonah’s declaration: “I want to go to the army.” He takes off his puppet and puts it on the floor, saying: “I, thank God, have finished with being a Jew.”

To what extent can we choose, and to what extent are we manipulated by the cultural story into which we are inscribed? In Berezin’s hands, the story of a simple man is never simple; it is implicated with irony and suffused with the poetry of loneliness and desire. Like the puppets, sewn of rough scraps, working with a limited palette of black, white and cream revealing the sensual nuances of texture, their faces traversed with seams, like different paths to the self, our identities are constructs of myth, memory and desire. Mendel’s piety is set against Dvora’s pragmatism: “You always remember the wrong pasuk (Biblical verse).”

Setting up the puppet as a visual, physical repository and symbol of Jewish identity, it exists within the play as something external that can be regarded, examined, and even discarded. Towards the latter part of the play, Mendel and Dvora sit at the table in “God’s own country” America, and Dvora – now Debra, reprimands Mendel: “You are talking like a Russian Jew.” Mendel responds, “I am a Russian Jew; that is who I am.” Yet this claiming or acceptance of identity is spoken by the actor facing the audience, the puppet head is slumped forward, inert, like a wilted flower.

Constantly setting up expectations and confounding them Berezin and an excellent ensemble cast create a magical evening, with stand-out performances by Ross and Nissim. At the end, he sends us back to the beginning, and we realize that we can re-enter the story from a different path, transformed by the experience shared on the stage.

Job, adapted by Roy Chen and Igor Berezin, directed by Igot Berezin

Set design, costume design and puppet design by Polina Adamov

Music: Evgeny Levitas

Lighting: Misha Tcherniavesky and Ina Malkin

Puppet movement: Yaara Boym-Kaplan

Movement: Ilya Domnot

Sword movement: Andre French Yudshkin

Tech Manager: Mike Nikitin

Tech team: Dima Svetov, Andre French Yudshkin

Performers: Dima Ross, Esti Nissim, Vadim Halif, Yonatan Bar-Or, Anat Gat, Yefim Rinberg, Ilya Domanov

AYELET DEKEL

[…] Golem on Wednesday, September 22, 2011. The adventurous experimental theatre (Orpheus in the Metro, Job: The Story of a Simple Man) takes their talents to explore new […]

You are absolutely right that all elements combine to create theatre. Writing a review immediately after seeing a play, there are sometimes unfortunate omissions in the process of writing. I have amended the text to reflect all the credits. It is also interesting that people rarely feel the need to make positive comments, as when I noted the set design for “New World Order” at the Khan: http://www.midnighteast.com/mag/?p=4976.

Wow! They did it without stage-designer, without dalls-designer, and without musician too?

You think, that it’s not importent in this show?

Comments are closed.