The retrospective exhibition of Moshe Gershuni, newly opened at the Tel Aviv Museum, is a major event in the cultural of life of this city. For 40 years, as artist and teacher, he has been a highly visible force, expressing his identity as an Israeli and a Jew in a way that no other artist before him has done.

Gershuni is a man of moral strength. Awarded the Israel prize in 1993, he refused to attend the ceremony (and the prize was eventually revoked) since he would then have to have shaken hands with Arik Sharon and the ministers of a government whose policies he abhorred.

The exhibition presents a large and impressive chronological selection of Gershuni’s art, with drawings and documentation from the 1970s heralding a feast of paintings drawn from every period in his career. Also displayed, and in the opinion of this writer, a lapse into kitsch, are his “Jewish Ceramics”, the swastika- decorated plates he produced in the late 1980s. In addition there is a set of strange sculptures, shown in public for the first time.

From the start of his career, Gershuni, was an artist with a mission. As a conceptualist in the 1970s, he explored alternative materials for making art, as illustrated, for example, in a painting contrived from blobs of cooking oil. On display, among these experimental pieces, is a small sheet of paper with its edges painted black, inscribed with the words: The paper is white outside, but black inside. This little drawing makes a point that Gershuni would later expand into the realm of symbol-laden, expressive painting – that seeing something is quite a different matter from understanding its meaning.

Gershuni catapulted onto the international arena in 1980 when he represented Israel (together with the artist Micha Ullman) at the Venice Art Biennale. In contrast to previous Israeli artists who exhibited there who wanted to appear ‘Western’ and international, Gershuni represented himself as an outsider, fearlessly revealing his feelings about Europe’s “sick past”. According to Sarah Breitberg-Semel, the curator of the present exhibition, he had an “open score to settle with Europe and had no intention of being polite or on his best behavior.” The installation Red Sealing/Theater was the result, documented in this exhibition through slides of the event.

Leaving untouched the pool of water that had accumulated on the floor of the Israeli pavilion during Venice’s rainy season, Gershuni sealed off the edges and corners of the gallery with red paint that quickly seeped into the water giving it the appearance of a bath of blood. The impression that something terrible had occurred in this place was heightened smears of red ‘blood’ and words like Arbeit scrawled across its walls. Among the few artifacts placed inside this space was a photo of Gershuni as a child taken on an Israeli beach in 1939; its presence there bonding Gershuni, and perhaps all Israel, with the persecuted Jewish children of Europe.

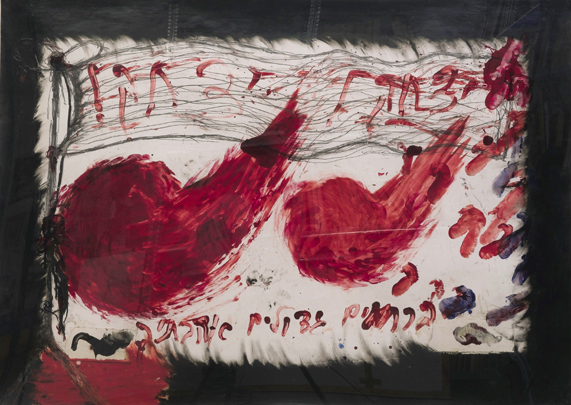

From this slide show one moves into the first of four large galleries where the tempestuous paintings that Gershuni produced on his return home are on display. Conceived in a harsh palette of blood-reds, blacks and sickly yellows, these works were not painted with brushes. Instead, he employed his whole hand to swipe glass paint, industrial varnish and oils onto white papers spread out on the floor.

The scribbled phrases, quotations from biblical texts and evocative images such as flags, uprooted trees and the Star of David that Gershuni integrated into these passionate works convey his horror and fear regarding the advent of war and the inevitable loss of young lives. In some cases, as in Yitzhak, Yitzhak, he focuses on a single repetitive image, in this case, a blood-red shape recalling the bloodied wing of a bird or a moving ball of fire. Effective parallels are made in many of these works between the Israeli soldier en route to war (‘I’m Coming I’m a Soldier’ is written into one painting) and Isaac, son of Abraham, journeying to the place of his sacrifice. In Gershwin’s view both are passive victims.

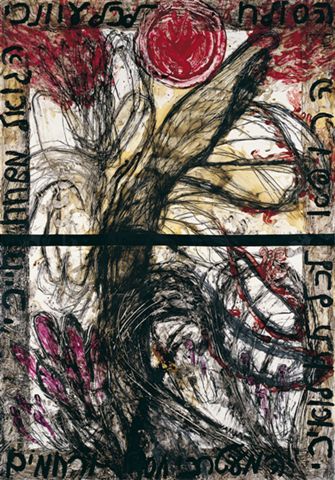

In Hai Cyclamen, the best known and most lyrical of all Gershuni’s painting series, Gershuni, employs cyclamens as an alternative image for Israeli soldiers. This exchange in identity is not new. In Haim Guri’s poem Bab al-Wad made into popular song commemorating the battle for Sha’ar HaGai in the War of Independence, “cyclamens will one day bloom” on the spot where soldiers fell in battle.

In this series, Gershuni’s frenzied approach has died down; every work is carefully ordered. The main motif of these paintings is not the flower itself, but the magnified forms of black roots, fronds and human limbs interspersed only here and there with the head of a flower or an individual leaf painted crimson. Each piece is edged with a dark border on which is inscribed a phrase or prayer.

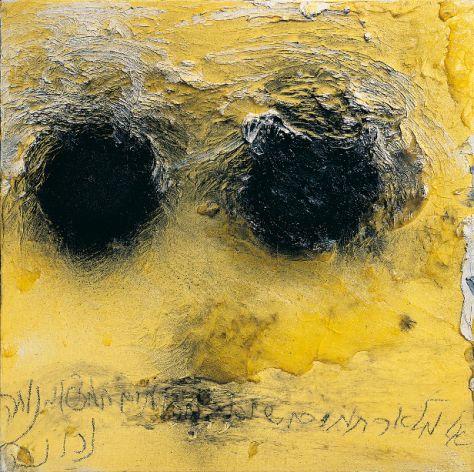

Into the 1990s, color drains out of Gershuni’s paintings and he tends to focus on motifs set against neutral backgrounds, having ambiguous meanings. Among them is a set of charcoal and oil renderings of wreaths (burial or victory symbols,) and paintings of black holes or blind eyes among them the mixed media piece God full of Mercy. This particular painting forms part of a mini-series titled Give Praise only to the Lord in which the words Ani Yodea? (Do I know?) taken from Ecclesiastes (3:21) is scrawled on the final piece. Is Gershuni, intimating here that there are things ‘twixt Heaven and Earth that he will never comprehend?

As noted above, the young Gershuni was intrigued by the concept of surface appearance vs. hidden content. Now, nearly 40 years later, when he turns his attention to sculpture for the first time, it seems that his interest in this topic was revived. A professed admirer of the Italian artist Medardo Rosso, a sculptor of figures whose features are invariably veiled over, it is perhaps not surprising to find that Gershuni tried for equivalent effects.

Selecting ready-made sculptures that the workmen in a bronze casting factory had already covered with clay in order to make a mold, Gershuni had these shrouded forms cast in bronze (without knowing what lay beneath.) The resultant pieces, some with sprues thrust into the ‘necks’, have a bizarre appearance. Gershuni calls them Sons of Chimneys. Some look like headless torsos, others like mummies; one, laid flat, recalls the stone effigies of royalty found inside Western cathedrals.

Four large and beautifully executed paintings make a suitable finale to this show. Dating from 2006 when Gershuni was already suffering from a dehabilitating illness, they are pure abstractions devoid of any of his signature motifs and symbols. Conceived in grey, white and black with touches of crimson, their paintwork coalesces into huge craggy shapes or thick rolling waves of pale color. They are true masterpieces.

.

The exhibition is accompanied by a fully illustrated book-catalog. Containing texts (Hebrew only) by Breitberg-Semel as well as transcripts of her interviews with the artist, it will undoubtedly prove to be the seminal work on Gershuni’s life in art. .

The exhibition will be open until February 26, 2011.

Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 27 Shaul HaMelech Blvd. Tel Aviv.

Hours: Sunday closed, Mon & Wed 10:00 – 16:00, Tues & Thurs 10:00 – 20:00, Fri 10:00 – 14:00, Sat 10:00 – 16:00. Information: 03-6077020 http://www.tamuseum.com

ANGELA LEVINE

Howdy! This is kind of off topic but I need some guidance from an established blog. Is it very difficult to set up your own blog? I’m not very techincal but I can figure things out pretty fast. I’m thinking about setting up my own but I’m not sure where to start. Do you have any tips or suggestions? Cheers

Four large and beautifully executed paintings make a suitable finale to this show. I am waiting for your next blog. I wish you all the best. Thanks 😉

Comments are closed.