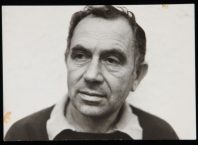

En route from one dance performance to another during International Exposure 2010, Midnight Night enjoyed an interesting conversation with Danish journalist Michael Bach Henriksen at the new Tola’at Sfarim (Bookworm) bookstore-café in the Chelouche Gallery art and cultural complex on 7 Mazeh Street. The choice of venue was not random – as Culture Editor of Kristeligt Dagblad (Danish – Christian Times) Henriksen often writes on literary topics, has a book out with Tonny Vorm – Stories of America: Recent Trends in American Literature (Bahnhoff 2010), and over the years has interviewed many Israeli authors, making a bookstore the most natural place to talk.

“It’s hard to find two more interesting countries than Israel and America,” says Henriksen, whose first encounter with Israel was ten years ago. His wife had been a volunteer in a kibbutz close to Haifa in the mid-80s, so there was a personal connection to their visit, in addition to a professional interest. The couple lived in Jerusalem from the fall of 1999 to March or April 2000, while Henriksen, who specializes in American Studies, finished working on his dissertation. An involvement with American Literature had led him to an interest in Jewish authors such as Saul Bellow and Phillip Roth, as well as an interest in Jewish issues. He felt that three books were particularly good preparation for his first visit: Saul Bellow’s To Jerusalem and Back, and Phillip Roth’s The Counterlife and Operation Shylock.

The Israel he recalls from that first stay was very different from the current scene, saying, “Barak was Prime Minister, there was a feeling that peace is just around the corner. We celebrated Christmas in Bethlehem.”

From Henriksen’s perspective, Jews and Israelis are both “so preoccupied with trying to find out what kind of Jew they are, what kind of Israeli they are.”

Since then, Henriksen has been back to Israel once more, as part of a Cultural Delegation organized by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 2009, this marks his third trip to Israel. In his conversations with Israeli writers, although many share similar, typically more left-wing political opinions with regard to issues such as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, in conversations with individuals one encounters a varied, complex picture. One writer who Henriksen notes as diverging from the perceived image is poet and novelist Miron Izakson with whom he discussed the Israeli re-discovery of Jewish religious roots. It was interesting for Henriksen to meet an Israeli writer, “a well known writer who is religious, and not critical of religion” challenging the preconception and showing “that writers and artists aren’t necessarily secular.”

“It’s really stimulating if you’re a curious person and trying to find out what this country is all about,” says Henriksen. Looking at the changes that have taken place in Israel since his first visit here, he says, “The peace movement and much of the left wing is, as everyone knows, is in a great crisis. When we lived here there was people talked about a real hope to end the conflict. Then I find a realism, or a cynicism among Israelis… the whole question of the conflict and the Palestinians seems to fade away, there’s no interest any longer, and that amazes me, because, I mean Gaza is only 40 kilometers from here and you can actually live an ordinary life and have everything, a normal existence without meeting signs of the conflict.”

At the same time Henriksen acknowledges the necessity of that ability to have “a normal existence,” saying, “It can also be a relief that you can go see arts on a very high level. Israelis are also occupied with things other than the conflict, and thank God they are.” He also commended the “vibrant Israeli cultural life” with its “lust for experiment.”

“The difference between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem is becoming much wider; Jerusalem is becoming much more religious than when we lived here, and that is maybe part of a normalization,” observes Henriksen, “Amos Oz told me last night that he thinks that Israel is becoming a much more normal country…the rise of religious fundamentalism that you see in America and in Arabic countries – so why wouldn’t you see that in Israel?” Reporting that Oz views the clash as not so much a religious issue as being between ‘fanatics’ and ‘people of reason,’ “He says the number of fanatics is increasing, some of the most fanatic people he [Oz] knows are engaged in the peace movement and the environmental movement, you really find some hard core reactionaries…” Henriksen says with a smile.

Returning to a more serious note, he says, “Israel is becoming more normal more American, more capitalistic, than when we lived here, also more modern. It used to be more ideologically based on the kibbutz, now you find that high tech and capitalism is the intention. It’s not a pioneering country any longer.”

“I’m curious to see where we will be in ten years if there is peace,” says Henriksen, as he notes, “The gap between rich and poor is growing, the gap between religious and secular is growing the gap between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem…there are really many poor people in Israel …I’m curious to find out because these tensions …I don’t know if Israelis can live with all these tensions. Because there is an outside threat – there is a threat from Iran, there is a threat from religious fundamentalism but what if that threat disappears one day? I hope it does, but Israelis have so many things they do not agree on. They do agree that they are threatened – and they are, really, I mean that. There are so many people who still hate Jews, it’s the same old story…but there’s a stabilizing factor, a threat can also be stabilizing.”

Recalling a recent conversation with Israeli author Lizzie Doron, he says, “She calls the whole of Israel one gigantic mental hospital.” When asked whether to the extent that one might characterize Israelis as involved with a questioning of their identity, would he describe Denmark as having a national character, Henriksen responds, “Yes, I certainly feel that our character, talking about national character and of course, there are a million exceptions to that…a country that has been so stable and well defined within borders and well defined as a nation, and a state, for not ages, but for many, many years. There is so much to take for granted in these countries, Norway, Sweden and Denmark. Because we never go to war and we never have political debates about which direction this country should take. There are some parts of the world where you don’t have stable nation/states in the same way. You’ve had this country for 60 years; you can trace an idea of Denmark many, many hundreds of years back. Egypt is also a rather new political entity that is also grappling with identity…and America is also a young country, and I think the wars have confronted America with what is the purpose of this country. The inhabitants of those countries are constantly confronted with the idea of their nation. 90 percent of all Danes are very similar, we believe the same, we are a very homogenous society, whereas coming to Israel it’s much more difficult to find out what is the national character. But at the same time, when you talk to people they are very convinced that they have found it.”

Comparing Denmark to Israel, Henriksen expresses the feeling that some degree of questioning can be beneficial, saying, “Once in a while it’s a good experience to ask oneself, what do you actually believe in?”

AYELET DEKEL

I am an American writer writing about a Danish journalist who rediscovers his family’s past history in the Danish West Indies and would like Mr. Henriksen to review a few pages (5-6) at most to see if the character sounds authentically Danish. (It’s not a major character, just a way to introduce his ancestors in the past.)

Would you be able to forward me contact information for Mr. Henriksen? I haven’t had much luck finding a Danish journalist.

Thanks!

Comments are closed.