Midweek. The sun is shining. Life is proceeding in a well-ordered fashion along Tel Aviv’s historic Rothschild Boulevard. But stop at building No. 12; climb the back stairway, push open a steel door and you find yourself in a huge, shabby space where normal speech is drowned out by a cacophony of noises, and one’s eyes are assailed by the multiple flickering of video screens. Facing the entrance door is a particularly revolting scene: artist Lior Shvil, in the role of a kosher butcher, gleefully hacking away at hunks of bloodied meat.

This is just one of a host of disturbing video works or mixed media installations created by 17 Israeli artists – angry men and women – exhibiting together under the provocative title of Neo-Barbarism.

To find the godfather of this group one has to look back almost 90 years, to the Dada Movement that sprang up in New York and Western Germany during and immediately after World War 1. Blaming society for wreaking havoc with the supposedly rational forces of science and technology, this group of artists, among them Jean Arp, Marcel Duchamp and our own Marcel Janco (at that time, a Romanian émigré living in Zurich,) rejected the whole history of art. The anti-art they proposed was confrontational, irrational, and often void of meaningful content.

Fast forward to 2011, and the Neo-Barbarians of Israel have taken up an equivalent stance. But the roots of their discontent lie elsewhere: in the character of contemporary Israeli society, its policies, its phobias and failures described by curators Naomi Aviv and Noam Segal in an outstanding catalog text as possessed by “unbearable moments of extremity, moments in which (our) culture is threatened by the civilization it has developed.”

Eti Wieselter’s video Reliques, a visually beautiful work, supplies the generational link between Dada and the Neo-Barbarians. Taking her underwater camera to the waters of Ras Muhammad in Sinai, she tracked the movement of large and small fish to a site at the bottom of sea where aquatic flora have become entangled with porcelain toilet seats. Her focus on these particular ‘ready-made’ objects is in fact a homage to Duchamp whose 1917 Urinal was a major landmark in 20th century art. It illustrated that the creative process that goes into a work is all important, and that the work itself can be made of anything, or take any form.

Since this is an art review, no attempt has been made to argue the rightness or validity of the political and socio-critical underpinnings of this show. Instead, it seeks to pinpoint some of the directions in which the exhibiting artists have shucked off rules and conventions. Almost all the participants can be compared to subversive moles burrowing under the surface of our lives. And yet, the messages their work projects are mostly ambiguous leaving the viewer to reach his/her own conclusions.

Dada had only one rule, never to follow any known rules. In the light of this axiom, several artists take aspects of control as their subject matter. Gal Weinstein’s 1.31 mins. video Can’t Put my Finger On explores in an ingenious and ‘artistic’ fashion the way that biometric surveillance equipment has reduced our identity to just a single finger mark. Dipping his finger in ink, he made a print of its whorls and lines on paper, creating an enlarged pattern in cotton wool glued to paper. Gradually setting fire to this image his fingerprint – and his whole identity – disappears in smoke.

Maya Zack’s fascinating piece Black and White Rule alludes to man’s fondness of subjugating animals to his own frivolous needs. And is, perhaps, also a metaphor for the oppressed rising up against their persecutors. Two white Poodles are the stars of her video. One space in which they are undergoing training has a chequered floor resembling a giant chess set. A trainer is teaching them ‘party’ tricks. But now and again, this man halts their instruction to perform a few tricks of his own. At one point, the dogs are given an injection, and then the relationship between the obedient animals and the trainer changes dramatically. The poodles attack him; a fight ensues resulting in the death of both the man and the dogs. These events and their conclusion -: a failed experiment in turning animals into machines for pleasuring human beings -are documented by a female scientist- observer.

A number of scenarios are bizarre in the extreme, disrupting the natural order of our existence. None more so than Sharon Balaban’s scenario where she offers her pregnant belly as alternative meat to a group of vultures feeding on the carcasses of dead animals. And then there is Totem, a portable installation, a sort of hurdy-gurdy, by Boaz Arad, that appears to celebrate the death of traditional family values. Religion, if one needs it, is represented here by a fertility idol placed atop a TV screen where Arad is engaged in feeding bread to his child, mouth-to-mouth. But in this case his child is a baby pigeon. Completing Arad’s happy ‘home’, strung from the underside of the TV table, are a store of worthless trinkets such as one might find as prizes in a claw grabbing machine. Here is something for everyone, nothing whatever to value or treasure.

The name Dada (Fr. a hobbyhorse) was chosen by the poet Tristan Tzara as being the nearest thing to meaningless babble. A number of works in this show like Karen Cytter’s video No Title Yet, also empty speech of its value. We see a stage where actors are interacting with each other, mostly in an aggressive fashion, expressing themselves in clichés or through repetitive sentences. To add to the sense of estrangement, voices do not emanate directly from the people who are talking. Backstage, the actors continue the same type of conversations. As a result the spectator is incapable of grasping any storyline, and doesn’t know what is real and what is staged. In effect, it seems that Cytter is highlighting the stultifying character of contemporary speech, a mirror reflection of the emptiness and superficiality of our lives.

Emptiness is also the theme of Roee Rosen’s video Hilarious in which the actress Hani Furstenberg plays a tacky stand up comedienne in a theater, spewing out a stream of obscene and trashy jokes that only embarrass her audience. Cleverly suggested here is the role that reality and stand-up shows have played in dumbing down our intelligence and wiping out our desire for quality entertainment.

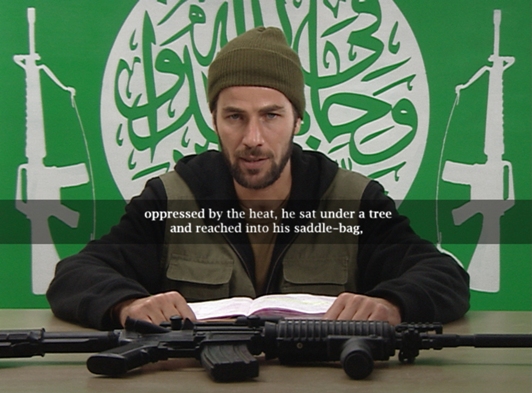

If one of the aims of this show is to shake people up, then Sharif Walid’s video loop To Be Continued would certainly be a contender. In it, the actor Salah Bakri plays the role of a Palestinian suicide bomber. He sits at a table, a gun laid out before him, a verse from the Koran pinned to the wall behind his head. This ‘terrorist’ reads from a paper that one assumes is a personal statement aimed at making him a hero and martyr in the eyes of comrades. But Walid has made an inspired choice of text by getting the actor to read instead from the Persian folk tale A Thousand and One Nights in which Scheherazade tells stories to her husband, the king, as a way of staying her execution. Finishing one story and immediately starting the next, she keeps him continuously enthralled.

Bakri has a captivating voice, and a very expressive face, and as he reads on without stopping, the viewer becomes transfixed by this scene and the sadness emoting from the man. The anger and bitterness that one would have felt at the sight of a terrorist justifying his actions, give way, albeit reluctantly, to deep sympathy for this human being, this teller of stories, who has found a way of postponing the moment of his own death and that of others.

This exhibition is not easy to come to terms with, its boldness, in some instances, shocks and bewilders. But this is exactly what these Neo-Barbarians are apparently seeking. As this writer sees it, the aims of this group can be summed up in a Dada statement made by Tzara many years ago: “Freedom: crying open the constricted pains, swallowing the contrasts and all the contradictions, the grotesqueries and the illogicalities of life.”

This Rothschild69 project is the inaugural annual exhibition of VIDEO 1.01. It was produced and supported by the New Israeli Film Foundation for Cinema and TV. Open until 15th January. Address: Rothschild69-Projects, 2nd Floor 12 Rothschild, Tel Aviv. info@rothschild69.co.il

ANGELA LEVINE