The first time I saw ‘The Social Network’, I thought it was a nice simple archetypal story about ambition with a bit of seasoning that was specific to today. Seeing it a second time, the ideas particular to this story came to the fore: the codes we speak in (and perhaps think in), the loss of privacy, class warfare, geeks as rock-stars, brilliance and invention in the socially maladroit- all under the general theme of ‘lack of connection’. The movie does a good job of presenting these ideas. But therein lies the problem- present them is all it does. It sometimes illustrates them with verve and wit -this is quite an entertaining movie, if you can past the somewhat icky nature of some of the characters- but with very few exceptions, it has no real insight, no sense of discovery or revelation.

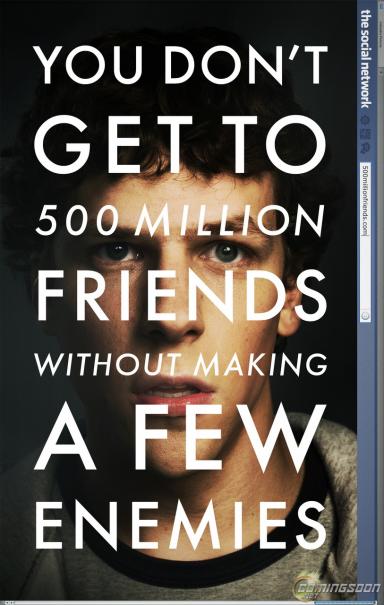

Now, director David Fincher is no slouch– in fact, he’s one of the most talented and interesting directors working- but without a doubt, the more prominent voice in this film is screenwriter Aaron Sorkin’s. Sorkin based the script on Ben Mezrach’s ‘The Accidental Billionaires’ (the facts of which are contested by some of the principles), and by his own admission immediately zeroed in on the universality of the story. He doesn’t much care about facts -a minor problem- or the specifics of the story -a major problem. The story in the film is one of the oldest, a tale of ambition, loyalty, friendship and how lonely it is at the top, launched by The One That Got Away. The film’s first scene –a dizzying verbal sparring match between future Facebook creator Mark Zuckerberg (Jesse Eisenberg) and his girlfriend (the charming Rooney Mara) neatly sets up the film. Mark is going on about the elite finishing club he wants to get into while insulting his girlfriend’s education, without ever realizing that she is breaking up with him- he thinks she’s speaking in code (He has to ask ‘Is this real?’). The rest of the film further illustrates the theme of this scene and -less than convincingly- his search for reconciliation/revenge (even he probably isn’t sure which).

This scene, like the rest of the film, is captured simply and directly by Fincher, whose work here is atypically subdued. Fincher has already shown with ‘The Curious Case of Benjamin Button’ an effort to branch out- tonally and thematically- from the harsher, sharper and bleaker films that made him famous (his first six films were ‘Alien3’, ‘Seven’, ‘The Game’, ‘Fight Club’, ‘Panic Room’ and ‘Zodiac’). ‘The Social Network’ is another notable departure. For the first time, he has put himself completely in the hands of his dialogue heavy script (the 121 minute film is the result of a 163 page script), with far less of the visual flourishes he is known for. He does have a distinct visual scheme here, one which subtly reinforces the film’s overarching theme of lack of connection. The cinematography is crisp and sharp, but with very shallow depth of field- typically, only one character in a given shot is in clear focus while the rest are increasingly blurry. Even when standing next to other people, Mark is isolated from them.

But even though that is effective, the theme of lack of connection feels like it is coming from people to whom this is a real discovery, when in fact that’s been written and talked about to death already (at times, this film feel like a dramatization of an op-ed piece). There is something curiously out of touch about the whole film, an unbalanced lack of specificity. Sorkin takes it as a point of pride that he knows or cares nothing about Facebook. So instead, he wrote to everything that makes it familiar as an archetypal story, and shows little interest in the actual achievements of the characters. This film seems to think that the social phenomenon which Facebook is a part of is not interesting in and of itself -it’s merely ironic, coming from such an anti-social person. The real point to them seems to be Messed up Genius Screws Friends on the Way to The Top- no less relevant today than ever, but no more so. ‘Lack of Connection’ is just window dressing; it’s not really dealt with. In fact, this entertaining fiction often feels nearly as disconnected as the characters it presents.

Now, that’s not to say that the film isn’t worth-while. As insanely over-hyped as it may be, it is on solid and very entertaining ground when dealing with class. After getting dumped in the opening scene, Mark almost immediately gets to getting revenge, and on the way creates the antecedent to Facebook (a site dedicated to grading the sexiness of the female students of Harvard). This is shown in a belabored but effective intercutting of the jocks in their decadent partying with the nerds who are changing the world so that one day, they too might be invited to the jocks’ party. Insiders vs. outsiders, Jews vs. WASPs, rich vs. middle class. Representing the insider/WASP/jock end of the conflict are Taylor and Cameron Winklevoss, identical silver-spoon twins, handsome Aryan jocks that the Jew-froed Zuckerberg mockingly calls ‘The Winklevi’.

Both are played -through some flawless digital trickery- by Armie Hammer, whose performance transcends the gimmick and is invaluable to the film. He makes the twins- written as a walking punch line- likable, even though they are just the foils for our main character. The twins allege that Zuckerberg stole their idea, and are on the sidelines of the film, following Zuckerberg’s success with helpless rage. In the film’s best scene, the privileged twins meet with Harvard president Larry Summers, attempting to stop Zuckerberg by citing the Harvard code. Summers, bemused and impatient, puts the twins in their place, telling them that they’ll get no special treatment because their father can get them a meeting with him (the fact that he’s a shlubby Jew and they’re dashing WASPs is not underlined, but it’s hard to miss). The movie implies that in the age of self-made men, the silver-spoons would be relics if not for the fact that the ultimate goal of self-made men is to fit in with them.

The film is framed by depositions for two different lawsuits that Zuckerberg is the target of. A major player in both is Eduardo Saverin (Andrew Garfield), Zuckerberg’s college roommate and best friend. In one he witnesses in Zuckerberg’s favor, in the other he is the one suing him. It is Saverin’s initial investment that makes Facebook possible, and he is the film’s resident good guy- to a fault. Although the film at various points shows different points of view on the events surrounding the creation of Facebook, in all of them, Saverin is the ‘aw, shucks’ hero- saintly at best, naive at worst. Garfield is very likable, but the stacking of the deck in his favor is quite egregious, especially when contrasted with Justin Timberlake as Napster creator Sean Parker. The Sean Parker of ‘The Social Network’ is a walking pile of sleaze –a petty, paranoid, vengeful, immature person, who by sheer moxy and sex-appeal guided Facebook into the ridiculously successful business model and exposure level it quickly achieved. Timberlake’s performance is fine, but it’s the idea of casting an uber-successful pop-star as Zuckerberg’s idol that does most of the acting for him. The filmmakers’ vision of the vengeful and jealous nerd is crystallized when we see Zuckerberg utterly transfixed by everything that comes out of this handsome Gordon-Gekko-wannabe (Zuckerberg barely seems interested when Bill Gates presents his dorky notions of success in a lecture early in the film- the cool, rebellious computer programmer as personified by Timberlake is the model he’s after).

Still, uninterested in the specifics as he they may be, Sorkin and Fincher do love the process of genius. They are clearly impressed with Zuckerberg, whose talents are shown not so much to be as a programmer or a social architect, but in the ability to apply one idea to the next. He is practically a savant- picking up on the crucial aspect of things that other miss. When the Winklevoss twins approach him with the idea of an exclusive online social network for Harvard students, his mind races ahead, realizing the potential for a far grander project. When someone makes a casual observation about a girl’s availability for dating, he comes up with the ‘Relationship Status’ field. ‘Facemash’, the antecedent to ‘Facebook’ that grades female students comes about when Mark applies Saverin’s algorithm for ranking chess players with the desire to get back at the whole Harvard-going female sex. And it is no small feat that Jesse Eisenberg manages to be utterly convincing when performing brilliance at work.

Eisenberg –who for five years has been the go to guy for awkward and precocious nerds- gives what is one of the least pandering main performances seen on film in recent years. In addition to being brilliant, Mark is petty, callous, selfish, cocky and mostly humorless. That the film is even bearable is a credit to Eisenberg, though he does get some help from the fact that this pathetic character is so unbelievably unlikable that one can’t help feel sorry for him. In fact, he’s used as something of a tabula rasa- even when presented with his point of view, we don’t get much of a sense of what he’s feeling (assuming that one doesn’t buy the filmmakers’ notion of a guy made of only brilliance, vengefulness and a desire to be cool). He’s mainly the object of Saverin’s puppy-dog like attempt to help his friend, and Saverin’s feelings of betrayal. The truth is probably somewhere in the middle- but the film is unreliable enough to leave me unconvinced of any of the character’s true nature as presented.

These thoughts come several weeks after the film was first released- I waited until I could see it a second time before writing about it, because my initial impression –a resounding ‘it’s okay’- seemed lacking in dealing with the most acclaimed movie of the year. The film is better the second time. But its rapturous reception is still something of a mystery to me.

SHLOMO PORATH